Using data from Nate Silver’s fivethirtyeight.com (click on the image for the full-sized version):

On the topic of US politics …

There’s a perennial question thrown around by Australian and British politics-watchers (and, no-doubt, by people in lots of other countries too, but I’ve only lived in Australia and Britain): Why do American elections focus so much on the individual and so little on the proposed policies of the individual? Why do the American people seem to choose a president on the basis of their leadership skills or their membership of some racial, sexual, social or economic group, while in other Western nations, although the parties are divided to varying degrees by class, the debate and the talking points picked up by the media are mostly matters of policy?

An easy response is to focus on the American executive/legislative divide, but that carries no water for me. Americans seem to also pick their federal representatives and senators in the same way as they do their president.

The best that I can come up with is to look at differences in political engagement brought about by differences in scale and political integration. The USA is much bigger (by population) and much less centralised than Australia or Britain. As a result, the average US citizen is more removed from Washington D.C. than the average Briton is from Whitehall or the average Australian from Canberra. The greater population hurts engagement by making the individual that much less significant on the national stage – a scaled-up equivalent of Dunbar’s number, if you will. The decentralisation (greater federalism) serves to focus attention more on the lower levels of government. The two effects, I believe, reinforce each other.

Americans are great lovers of democracy at levels that we in Australia and Britain might consider ludicrously minuscule and at that level there is real fire in the debates over specific policies. Individual counties vote on whether to raise local sales tax by 1% in order to increase funding to local public schools. Elections to school boards decide what gets taught in those schools.

That decentralisation is a deliberate feature of the US political system, explicitly enshrined in the tenth amendment to their constitution. But when so many matters of policy are decided at the county or state level, all that is left at the federal level are matters of foreign policy and national identity. It seems no surprise, then, that Americans see the ideal qualities of a president being strength and an ability to “unite the country.”

Did Toot win it for Obama?

You can file this under “Things that Democrats in America wouldn’t dream of saying out loud.” Did Obama’s visit to his close-to-death grandmother seal his victory in the upcoming election? Think of what it says:

- Firstly, there is an immediate comparison to when John McCain suspended his own campaign. That was ostensibly to find a solution to the financial crisis, but as it happens, the details of the bailout were agreed on before he ever got to Washington, the American public didn’t like it and McCain got tarred with that frustration. Even worse, the McCain suspension looked like precisely what it was – a cheap stunt. In comparison, Obama’s campaign suspension could not possibly be more authentic. He is going to tend to his sick grandmother.

- Secondly, it humanises Obama by giving people a genuine insight into the man’s personal life. Even more, it is something that everybody in the country – Democrat or Republican – can relate to.

- Thirdly, it emphasises the age difference between Obama and McCain. Grandparents can get sick and (sadly) die. John McCain is of grandparent age, while Obama is a vibrant, healthy adult. No matter how fit McCain is, that hurts him.

- Fourthly, it either forces the McCain campaign to stop the all-negative ads for a couple of days or, more likely, makes them look low and nasty for keeping them going. Since all politics is relative, that raises Obama up, which brings us to …

- Finally, it paints Obama in the colours of what the American electorate loves best: personal strength in the face of adversity. Fortitude in the face of grief. It is what people admire in their war-time presidents, grimly bearing witness to the coffins of the “glorious dead” and providing a symbol of a man unbowed by the ugly aspects of human existence.

Yes, okay, it’s probably fair to say that Obama was coasting to victory long before his campaign announced his intention to go to Hawaii. But that’s not the point. The point is that it will have helped. Were it a close race, this may have decided it. As it stands, it guarantees that McCain can’t claw back any of Obama’s lead during those two days, making the Republican turn-around that much less likely.

That’s quite a jump

Following on from observing that Obama’s fundraising (and therefore advertising) success gives Republicans an excuse for losing the upcoming election, I see the following:

In August 2008, the Obama campaign set a record for the most successful fundraising month ever for a US presidential campaign: $66 million.

On the 29th of August 2008, John McCain presented Sarah Palin as his vice-presidential candidate.

In September 2008, the Obama campaign blows their August fundraising figure out of the water, this time managing over $150 million.

Obama’s spending gives Republicans an excuse

So Barack Obama is easily outstripping John McCain both in fundraising and, therefore, in advertising. I’m hardly unique in supporting the source of Obama’s money – a multitude of small donations. It certainly has a more democratic flavour than exclusive fund-raising dinners at $20,000 per plate.

But if we want to look for a cloud behind all that silver lining, here it is: If Barack Obama wins the 2008 US presidential election, Republicans will be in a position to believe (and argue) that he won primarily because of his superior fundraising and not the superiority of his ideas. Even worse, they may be right, thanks to the presence of repetition-induced persuasion bias.

Peter DeMarzo, Dimitri Vayanos and Jeffrey Zwiebel had a paper published in the August 2003 edition of the Quarterly Journal of Economics titled “Persuasion Bias, Social Influence, and Unidimensional Opinions“. They describe persuasion bias like this:

[C]onsider an individual who reads an article in a newspaper with a well-known political slant. Under full rationality the individual should anticipate that the arguments presented in the article will reect the newspaper’s general political views. Moreover, the individual should have a prior assessment about how strong these arguments are likely to be. Upon reading the article, the individual should update his political beliefs in line with this assessment. In particular, the individual should be swayed toward the newspaper’s views if the arguments presented in the article are stronger than expected, and away from them if the arguments are weaker than expected. On average, however, reading the article should have no effect on the individual’s beliefs.

[This] seems in contrast with casual observation. It seems, in particular, that newspapers do sway readers toward their views, even when these views are publicly known. A natural explanation of this phenomenon, that we pursue in this paper, is that individuals fail to adjust properly for repetitions of information. In the example above, repetition occurs because the article reects the newspaper’s general political views, expressed also in previous articles. An individual who fails to adjust for this repetition (by not discounting appropriately the arguments presented in the article), would be predictably swayed toward the newspaper’s views, and the more so, the more articles he reads. We refer to the failure to adjust properly for information repetitions as persuasion bias, to highlight that this bias is related to persuasive activity.

More generally, the failure to adjust for repetitions can apply not only to information coming from one source over time, but also to information coming from multiple sources connected through a social network. Suppose, for example, that two individuals speak to one another about an issue after having both spoken to a common third party on the issue. Then, if the two conferring individuals do not account for the fact that their counterpart’s opinion is based on some of the same (third party) information as their own opinion, they will double-count the third party’s opinion.

…

Persuasion bias yields a direct explanation for a number of important phenomena. Consider, for example, the issue of airtime in political campaigns and court trials. A political debate without equal time for both sides, or a criminal trial in which the defense was given less time to present its case than the prosecution, would generally be considered biased and unfair. This seems at odds with a rational model. Indeed, listening to a political candidate should, in expectation, have no effect on a rational individual’s opinion, and thus, the candidate’s airtime should not matter. By contrast, under persuasion bias, the repetition of arguments made possible by more airtime can have an effect. Other phenomena that can be readily understood with persuasion bias are marketing, propaganda, and censorship. In all these cases, there seems to be a common notion that repeated exposures to an idea have a greater effect on the listener than a single exposure. More generally, persuasion bias can explain why individuals’ beliefs often seem to evolve in a predictable manner toward the standard, and publicly known, views of groups with which they interact (be they professional, social, political, or geographical groups)—a phenomenon considered indisputable and foundational by most sociologists[emphasis added]

While this is great for the Democrats in getting Obama to the White House, the charge that Obama won with money and not on his ideas will sting for any Democrat voter who believes they decided on the issues. Worse, though, is that by having the crutch of blaming the Obama campaign’s fundraising for their loss, the Republican party may not seriously think through why they lost on any deeper level. We need the Republicans to get out of the small-minded, socially conservative rut they’ve occupied for the last 12+ years.

Where is Obama’s big speech on sexism?

I can’t write much at the moment – exams – but it just occurred to me to ask: Where is Obama’s big speech on sexism?

Why didn’t he give a month ago? In particular, why didn’t he give it before the DNC made their decision on Florida and Michigan? Giving it after Hillary bows out will look like what it will be – a naked political attempt to convince her most ardent supporters to turn up on the first Tuesday after the first Monday of November. If he’d given it two months ago, it would have had at least a chance of being seen as an honest, even gracious attempt to reach out to the Hillary-voters and convince them that he believes in fighting all forms of bigotry.

Non-geographic constituencies

The Australian House of Representatives has 150 members for a resident population of 21,268,746 (10 April 2008), or almost 142,000 people per representative. The US House of Representatives has 435 members for a resident population of 303,817,103 (10 April 2008), or almost 670,000 people per representative. The UK House of Commons has 646 members for a resident population of 60,587,000 (mid-2006), or almost 94,000 people per representative. The Canadian House of Commons has 308 members for a resident population of 33,231,725 (10 April 2008), or almost 108,000 people per representative.

Traditionally, which is to say always, the constituency of each representative or member of parliament has been defined geographically. That’s simple enough, but now that communication and identification technology has advanced to where it is today, they no longer need to be.

Members of the various lower houses of parliament/congress are meant to be representatives of their constituents, speaking on their behalf and seeking to act in their best interest. Before anybody mentions it, the Edmund Burke argument, that members of parliament ought to focus on the well-being of the nation as a whole, carries more strength in a unicameral parliament than it does in the constitutional arrangements of Australia, Canada and the USA where an upper-house exists with members sitting for longer terms so as – in principal, at least – to focus more on the issues more than the politics. It also seems to me that within her role as a member of parliament thinking of the good of the nation, a representative has a duty to pass on to the parliament the democratically valid views of her constituents, even if she ultimately votes in another direction.

By having electoral districts be geographically defined, we remove from the people the right to self-organise and they instead become passive receivers of groupings that are set down upon them. Unless you have an independent body to determine electoral boundaries, you therefore run the risk of gerrymandering (although whether that necessary causes polarisation is apparently debatable). Even if gerrymandering does not cause polarisation, the relevance of a geographically-defined groups is becoming less relevant as communication and transportation technologies improve. In a more globalised world where the economic fortunes of people are less tied to those of their neighbours, the issues of concern that people share will be less likely to be spatially concentrated.

My question, then, is this: What if 150,000 Australians were to voluntarily opt out of their resident electoral districts and form a non-geographically defined constituency with their own seat in the House of Representatives?

- Individuals would only be permitted to be a member of one electoral constituency.

- Everyone would be a part of a geographic district by default, but could change to a non-geographic grouping if they chose.

- Even then, people would retain a geographical link to the legislature through the Senate.

- The election of representatives from non-geographic constituencies would proceed just like any other seat in a general election; all of the various political parties would be free to offer candidates and to campaign in whatever way they saw fit.

- By coming together around a common topic of concern, constituents guarantee that candidates will need to address that concern in their campaigns and that the winner will truly be their representative in parliament.

The idea isn’t entirely novel. Several countries allow for an expatriate electoral role so that non-resident citizens can still vote. These are usually tied back to a geographic district within the home country, but there’s no reason they have to be.

At a first glance, this might seem like a finely grained version of proportional representation. I guess that to a point it is, but since each constituency would still have elections, all parties would be able to put forward candidates and the decision process within each constituency would still be the same as within geographic districts (preferential voting in Australia, first-past-the-post in the UK and USA), it’s not.

It might also seem like this would just be formalised lobbying. To that I can only say: “Yes. So?” People are entitled to their views and in a democracy those views ought to be granted equal rights to be heard. Lobbyists are treated with such scorn today because they seek to obtain political influence beyond their individual vote. They exist, in part, because people do not have any real connection to their representatives.

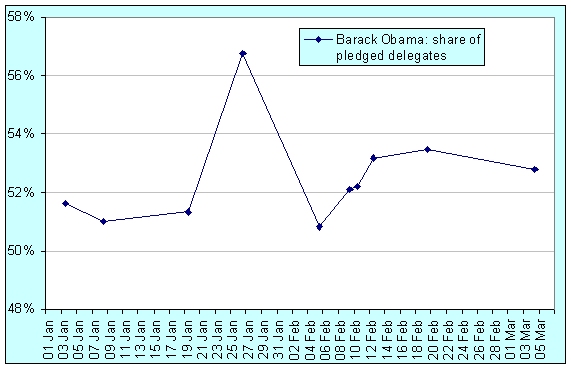

An update of my Obama numbers

Taking the data from Real Clear Politics today (14 March), here is an update of how Obama and Clinton have been going in running totals of pledged delegates:

As always, when calculating the percentages in the centre column, I’m ignoring pledged delegates that are too close to call and those with John Edwards.

| Date | Barack Obama: running total | Barack Obama: share of pledged delegates | Hillary Clinton: running total |

| 3 Jan (IA) | 16 | 51.6% | 15 |

| 8 Jan (NH) | 25 | 51.0% | 24 |

| 19 Jan (NV) | 38 | 51.4% | 36 |

| 26 Jan (SC) | 63 | 56.8% | 48 |

| 5 Feb (Super Tuesday) | 913 | 50.9% | 879 |

| 9 Feb (LA, NE, WA, Virgin Is.) | 1019 | 52.2% | 934 |

| 10 Feb (ME) | 1034 | 52.3% | 943 |

| 12 Feb (DC, MD, VA, Dem.s Abroad) | 1144 | 53.3% | 1004 |

| 19 Feb (HI, WI) | 1200 | 53.5% | 1041 |

| 04 Mar (OH, RI, TX, VT) | 1380 | 52.9% | 1227 |

| 08 Mar (WY) | 1387 | 53.0% | 1232 |

| 11 Mar (MS) | 1406 | 53.0% | 1246 |

There are now 566 pledged delegates to fight for (assuming that Florida and Michigan don’t get redone), 26 with John Edwards and 9 that have been voted on but are still too close to call.

The gap in pledged delegates between the candidates is now 160.

I assume that the 35 delegates that are with Edwards or too close to call will be split 50-50 between Obama and Clinton. I actually believe that Obama will get more than half of them (22 of Edwards’ delegates came from states where Obama won) but let’s be generous and say that 18 go to Clinton and 17 to Obama.

That means that Clinton needs to close a gap of 159 with only 566 pledged delegates to come. She needs to win 363 or 64%. To stay in front, Obama only needs to win 204 or 36%.

If Florida and Michigan are redone, then we have 879 delegates to come, from which Clinton would need to win 519 or 59%. To stay in front, Obama would only need to win 361 or 41%. Given its large population of Hispanics, it seems clear that Clinton would do well in Florida, so it’s pretty obvious why she wants these two states back in play.

But is it plausible to think that she can win among pledged delegates? No, not really; not even if Florida and Michigan do get redone.

On the basis of pledged delegates, Clinton has only won 13 out of 46 contests so far. On the basis of popular vote, she has won 14 out of 40; 16 if you include Florida and Michigan (Iowa, Maine, Nevada and Washington haven’t released their popular vote counts).

In those states she won in pledged delegates, Clinton has averaged 57% of the delegates on offer: she got 688 to Obama’s 517.

So in order to win overall among pledged delegates, Clinton needs to win all 12 (if FL and MI are included) remaining contests and do better in every one of them than she has previously in her winning states. If she loses any of them, then she’ll need to absolutely blow Obama out of the water in the rest. I just can’t see this happening.

Barack Obama will still win the Democratic nomination

There’s my prediction. The idea that Democratic Party super-delegates will side with the winner among pledged delegates has gone mainstream, with Jonathan Altar writing yesterday in Newsweek: “Hillary’s New Math Problem“.

Superdelegates won’t help Clinton if she cannot erase Obama’s lead among pledged delegates, which now stands at roughly 134. Caucus results from Texas aren’t complete, but Clinton will probably net about 10 delegates out of March 4. That’s 10 down, 134 to go. Good luck.

I’ve asked several prominent uncommitted superdelegates if there’s any chance they would reverse the will of Democratic voters. They all say no. It would shatter young people and destroy the party.

I’ve been saying this for a while (here, here, here and here). Altar suggests that if Clinton can at least win the overall popular vote, she might have an argument, but even that’s going to be hard, to say the least. Obama will certainly win a majority of states (he already has), will almost certainly win a majority of pledged delegates and will probably win a majority of the popular vote. There is no way that the super-delegates won’t come down on his side.

As it stands, using the Real Clear Politics figures, 2642 out of 3253 pledged delegates have been decided: there are 611 left to play for, 28 unallocated yet because they’re still too close to call and 26 are with John Edwards. Assuming that the unallocated and Edwards delegates split 50-50, Obama currently has a pledged-delegate lead of 144. To catch up, Clinton needs to win 378 of the remaining 611, or 61.8%. To stay ahead, Obama only needs to win 234 of the 611, or 38.3%. It would take a minor miracle for Obama to lose the pledged-delegate race.

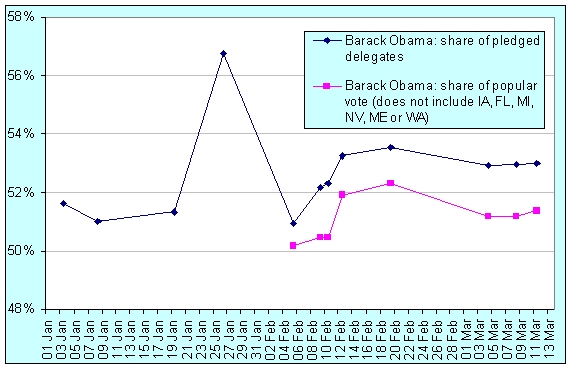

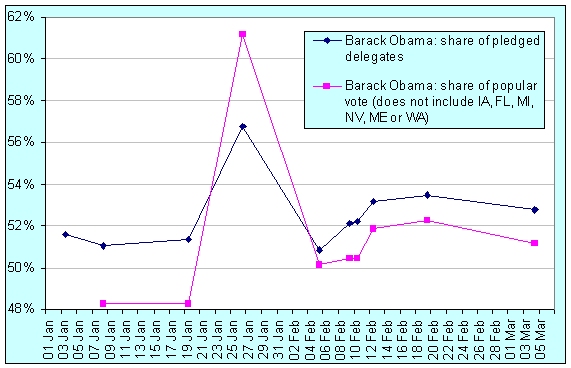

On the popular vote side, it’s a little hard to make a fair comparison. Several states have not released the number of voters, while Michigan and Florida make things complicated. With all of those states ignored, Obama still has a serious, albeit smaller, lead (N.B: popular-vote figures prior to 26 Jan should be taken with a very large grain of salt):

People looking to a Clinton win in the popular vote are eyeing off her performance in Michigan and Florida, but Obama did no campaigning in these states (he wasn’t even on the ballot in Michigan) and for these states to be counted, they will need to be rerun. Florida does have a large Hispanic population, but even if Clinton expands her winning margin there, it probably won’t make up for her losses in Michigan.

I was right, pretty-much-right and wrong all at once!

The girl’s got spunk. Back on the 20th of Feb, I predicted that while Hillary Clinton would win the popular vote in Ohio and Texas, she would barely win in the pledged delegates from those states. On that basis, I further predicted that Clinton would be written off by the 10th of March, even if she hadn’t conceded yet.

As evidence that you should always quit while you’re ahead, I was right on the first prediction, pretty-much-right on the second and, it would seem, not even close to being right on the third. Clinton won the popular vote in both states (1.46 million vs. 1.36 in Texas, 1.21 vs. 0.98 in Ohio). In the pledged-delegate counts, Clinton currently leads 92-91 in Texas (10 still too close to call) and 74-65 in Ohio (2 still too close to call). My prediction was bang on the money in Texas, but arguably a bit wide of the mark in Ohio. But when it comes to considering the on-going Clinton campaign, nobody is talking about Howard Dean tapping Clinton on the shoulder for a quiet chat now; all talk is about Pennsylvania in six weeks’ time.

That is a remarkable story and not because of the 3am telephone call or Obama’s views on NAFTA (although those certainly helped Clinton), but because of the successful lowering of expectations that the Clinton campaign managed to bring about. Immediately after Wisconsin and Hawaii, all talk was that Clinton needed to win, and win big, in both Texas and Ohio in order to go on. A week ago the talk was that she could justify going on if she won with a wide margin in at least one of them. In the day or two before, the word was that she would push on if she at least one the popular vote in one of the two. That lowering of expectations meant that when she won both popular votes by a solid margin and both delegate counts (albeit by small margins), it looks like a blow-out for her and gives the impression of renewed momentum.

My original observation, that Barack Obama has been in front since day one, still holds true. Using the data at Real Clear Politics, the running totals for pledged delegates have been:

| Date | Barack Obama: running total | Barack Obama: share of pledged delegates | Hillary Clinton: running total |

| 3 Jan (IA) | 16 | 51.6% | 15 |

| 8 Jan (NH) | 25 | 51.0% | 24 |

| 19 Jan (NV) | 38 | 51.4% | 36 |

| 26 Jan (SC) | 63 | 56.8% | 48 |

| 5 Feb (Super Tuesday) | 906 | 50.8% | 876 |

| 9 Feb (LA, NE, WA, Virgin Is.) | 1012 | 52.1% | 931 |

| 10 Feb (ME) | 1027 | 52.2% | 940 |

| 12 Feb (DC, MD, VA, Dem.s Abroad) | 1137 | 53.2% | 1001 |

| 19 Feb (HI, WI) | 1193 | 53.5% | 1038 |

| 04 Mar (OH, RI, TX, VT) | 1366 | 52.8% | 1222 |