From Brad DeLong, this tickled my fancy:

In the email inbox:

In Agatha Christie’s autobiography, she mentioned how she never thought she would ever be wealthy enough to own a car – nor so poor that she wouldn’t have servants…

Research Economist at the Bank of England

From Brad DeLong, this tickled my fancy:

In the email inbox:

In Agatha Christie’s autobiography, she mentioned how she never thought she would ever be wealthy enough to own a car – nor so poor that she wouldn’t have servants…

Continuing on from my previous thoughts (1, 2, 3, 4) …

In the world of accounting, the relevant phrase here is “fair value.” In the United States (which presently uses a different set of accounting requirements to the rest of the world, although that is changing), assets are classified as being in one of three levels (I’m largely reproducing the Wikipedia article here):

Level one assets are those traded in liquid markets with quoted prices. Fair value (in a mark-to-market sense) is taken to be the current price.

Level two and level three assets are not traded in liquid markets with quoted prices, so their fair values need to be estimated via a statistical model.

Level two assets are those whose fair value is able to be estimated by looking at publicly-available market information. As a contrived example, maybe there is currently no market for a particular AA-rated tranche of CDOs, but there are recent prices for the corresponding AAA-rated and A-rated tranches, so the AA-rated stuff should be valued somewhere in between those two.

Level three assets are those whose fair value can only be estimated by appealing to information that is not publicly observable.

These are listed in the U.S. Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Statement 157. In October of last year, the FASB issued some clarification/guidance on valuing derivatives like CDOs when the market for them had dried up.

Brad DeLong, in early December last year, was given a list of reasons from Steve Ross why we might not want to always mark-to-market (i.e. assume that the fair value is the currently available market price):

- If you believe in organizational capital–in goodwill–in the value of the enterprise’s skills, knowledge, and relationships as a source of future cash flows–than marking it to market as if that organizational capital had no value is the wrong thing to do.

- Especially as times in which asset values are disturbed and impaired are likely to be times when the value of that organizational capital is highest.

- If you believe in mean reversion in risk-adjusted asset values, mark-to-market accounting is the wrong thing to do.

- If you believe that transaction prices differ from risk-adjusted asset values–perhaps because transaction prices are of particular assets that are or are feared to be adversely selected and hence are not representative of the asset class–than mark-to-market accounting is the wrong thing to do.

- If you believe that changes in risk-adjusted asset values are unpredictable, but also believe:

- in time-varying required expected returns do to changing risk premia;

- that an entity’s own cost of capital does not necessarily move one-for-one with the market’s time-varying risk premia;

- then mark-to-market accounting is the wrong thing to do.

The interest rates on US government debt has turned negative (again) as a result of the enormous flight to perceived safety. I guess they’ll be able to fund their gargantuan bailouts more easily, at least.

Brad DeLong has written a short and much celebrated essay (available on Cato and his own site) on the financial crisis and (consequently) why investors currently love government debt and hate everything else. I’ll add my voice to those suggesting that you read the whole thing. Here is the crux of it:

[T]he wealth of global capital fluctuates … for five reasons:

- Savings and Investment: Savings that are transformed into investment add to the productive physical — and organizational, and technological, and intellectual — capital stock of the world. This is the first and in the long run the most important source of fluctuations — in this case, growth — in global capital wealth.

- News: Good and bad news about resource constraints, technological opportunities, and political arrangements raise or lower expectations of the cash that is going to flow to those with property and contract rights to the fruits of capital in the future. Such news drives changes in expectations that are a second source of fluctuations in global capital wealth.

- Default Discount: Not all the deeds and contracts will turn out to be worth what they promise or indeed even the paper that they are written on. Fluctuations in the degree to which future payments will fall short of present commitments are a third source of fluctuations in global capital wealth.

- Liquidity Discount: The cash flowing to capital arrives in the present rather than the future, and people prefer — to varying degrees at different times — the bird in the hand to the one in the bush that will arrive in hand next year. Fluctuations in this liquidity discount are yet a fourth source of fluctuations in global capital wealth.

- Risk Discount: Even holding constant the expected value and the date at which the cash will arrive, people prefer certainty to uncertainty. A risky cash flow with both upside and downside is worth less than a certain cash flow by an amount that depends on global risk tolerance. Fluctuations in global risk tolerance are the fifth and final source of fluctuations in global capital wealth.

In the past two years the wealth that is the global capital stock has fallen in value from $80 trillion to $60 trillion. Savings has not fallen through the floor. We have had little or no bad news about resource constraints, technological opportunities, or political arrangements. Thus (1) and (2) have not been operating. The action has all been in (3), (4), and (5).

As far as (3) is concerned, the recognition that a lot of people are not going to pay their mortgages and thus that a lot of holders of CDOs, MBSs, and counterparties, creditors, and shareholders of financial institutions with mortgage-related assets has increased the default discount by $2 trillion. And the fact that the financial crisis has brought on a recession has further increased the default discount — bond coupons that won’t be paid and stock dividends that won’t live up to firm promises — by a further $4 trillion. So we have a $6 trillion increase in the magnitude of (3) the default discount. The problem is that we have a $20 trillion decline in market values.

Some people have criticised Brad for his characterisation of the liquidity discount, suggesting that he has confused it with the (pure) rate of time preference. I don’t think he is confused. Firstly because he’s a genuine expert in the field and if he’s confused, we’re in big trouble; and secondly because the two concepts are interlinked.

The liquidity discount is that an inability to readily buy or sell an asset – typically evidenced by low trading volumes and a large bid/ask spread – reduces it’s value.

The pure rate of time preference is a measure of impatience. $1 today is preferred over $1 tomorrow even if there is no inflation. [Update: see below]

The two are linked because if you want to sell assets in an illiquid market, you can either sell them at a huge discount immediately or sell them gradually over time. The liquidity discount is (presumably) therefore a monotonically increasing function of the pure rate of time preference for a given level of liquidity.

Minor update:

A more correct illustration of the pure rate of time preference would be to say:

Suppose that you could get a guaranteed (i.e. risk-free) annual rate of return of 4% and there is no inflation. A positive pure rate of time preference says that $1 today is preferred over $1.04 in a year’s time.

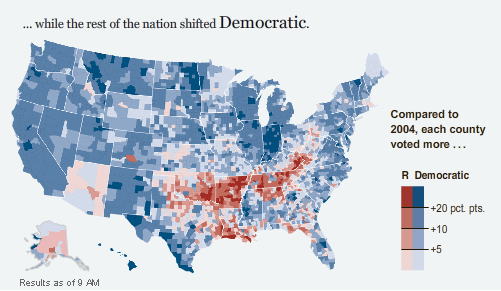

Brad Delong observes that there is a clear regional exception to the idea of a broad shift in the vote from the Republicans to the Democrats (the original scatterplot comes from Andrew Gelman):

Paul Krugman takes it a bit further, emphasising this beauty of a map (I’m not sure of the source. Probably the NY Times?):

The shifts to the Republicans in Arizona and Alaska and to the Democrats in Illinois and Delaware are clearly down to the candidates coming from those states. I’m a little surprised at the strength of the Republican shift in southern Louisiana. One might have thought that with the memory of Hurricane Katrina they would have moved blue. Perhaps the administration’s management of Hurricane Gustav was seen as successful? The Oklahoma-Arkansas-Tennessee shift is presumably McCain’s “real America.” I’d love to see a demographic breakdown of the vote in those states.

Almost immediate update:

dbt on Brad Delong’s blog points out the obvious about Louisiana:

Don’t lump Louisiana into that. The changes there are demographic, not electoral.

Which of course must be the explanation. Southern Louisiana didn’t turn red because of the success of the handling of Gustav; it turned red because of the failure to handle Katrina – vast numbers of black Americans were forced out and haven’t come back.

Continuing on from my previous wondering about how panic-driven and effective current US (monetary) policy is, I notice these two posts from Paul Krugman …

Ben Bernanke has cut interest rates a lot since last summer. But can he make a difference? Or is he just, as the old line has it, pushing on a string?

Here’s the Fed funds target rate (red line) — which is what the Fed actually controls — versus the interest rate on Baa corporate bonds (blue line), which is probably a better guide to what matters for actual business spending.

It’s pretty grim. Basically, deteriorating credit conditions have offset everything the Fed has done. Doubleplus ungood.

… and Brad DeLong …

Further cuts in the federal funds rate are on the way. Ben Bernanke is talking about how we are in a slow-moving financial crisis of DeLong Type II: one in which large financial institutions are insolvent–“pressure on bank balance sheets”–and in which lower short-term interest rates and a steeper yield curve are a way of providing institutions with the life jackets they need to paddle to shore.

Larry Meyers has pointed out that the BBB yield is no lower than it was in July–that all the easing has had no effect on the cost of capital that the financial markets feed to the “real economy,” and hence that Fed policy today is no more stimulative than it was last summer.

I’m more inclined to agree with Brad’s assessment than Paul’s implicit prediction of gloom, although it depends on what you think the Fed should be looking at. Paul is clearly hoping for a decrease in long-term rates so-as to stimulate the real economy, while Brad is simply noting that steeper yield curves, manifested here through a drop in base rates and no movement in longer-term paper, are pumping up banks’ profit flows, which will help them deal with the hideous losses from the sub-prime mess, the monoline insurer implosion and all the other nasties out there.

This seems like pretty clear “Bernanke put” behaviour to me. The banks need the short-term increase in profit flows in order to stay solvent in the medium-term. Whether Mr Bernanke is pushing down the base rate because the banks can’t lift the yields on long-term debt or because he doesn’t want them to (since that would hit the real economy) is a moot point.

This doesn’t change the fact that Bernanke is slopping out the good times to save the industry from its own mistakes. It’s probably safe to say that there’ll be no more knuckles rapped (except maybe those of the ratings agencies), so the real question is whether they’ll be allowed to make the same mistakes again …

“There is nothing a government hates more than to be well-informed; for it makes the process of arriving at decisions much more complicated and difficult.”

— John Maynard Keynes, The Times (March 11, 1937); Collected Writings, vol. 21, p. 409

(via Bruce Bartlett (via Brad DeLong))

Ahhh … the sweet, soothing succour of cynicism. 🙂

I’ve been wanting to write an essay on this for ages, but every time I think or talk to someone about it, I get hit with more ideas and different approaches. In the interests of not forgetting them, I thought it might be worthwhile formalising, if not my opinions, then at least the topics that I want to write on. I’m very interested in people’s opinions on these, so if you have a particular view, please leave some comments.

Brad DeLong has mused on the purpose of a course in political economy:

This is where we cash in our winning intellectual bets, tie all the threads together, and come up with running code for a rough-and-ready framework for thinking about everything that happens at the crossroads where history and politics meet economies and sociologies in a world where village elders along the Zambezi lecture the principal deputy managing director of the International Monetary Fund on the implications of the Republican convention.

I sat in on a few lectures for LSE’s graduate-level course in this stuff over the last year (I may yet take it formally as my second optional) and I have to say that I find Brad’s vision a lot more interesting. Perhaps I should be doing my PhD at Berkeley?

I love the internet. I love what it’s becoming, what it’s capable of becoming. A few years ago, the blogosphere (I hate that word) was dominated by enthusiastic amateurs. That is, it was filled with people who, in so far as they had any speciality, had it in entirely separate fields, but were interested in the topics they wrote about. It still is, and that’s great. Public debate is always good.

But now we are seeing professional thinkers stepping into the arena. University professors are emerging from their ivory towers and using the web to debate each other in the public sphere. That is freakin’ awesome. Here’s a recent example …

Patricia Cohen, of the New York Times, wrote this piece: In Economics Departments, a Growing Will to Debate Fundamental Assumptions. In it she quoted the views of, among others, Alan Blinder (Princeton), David Card (U.C. Berkley) and Dani Rodrik (Harvard).

It elicited quite a response in the various academic blogs. Three of them that are worth checking out:

It’s that last one by Don Boudreaux that I want to focus on. In it, he criticised the views of Dani Rodrik in particular and issued Dani a challenge.

Dani Rodrik replied: What’s different about international trade?

Brad DeLong (U.C. Berkley) was watching and gave his opinion: Don Boudreaux vs. Dani Rodrik on Industrial Policy: I Call This One for Don–I Think It’s a Knockout

Dani Rodrik then updated his original post with a rebuff to Brad DeLong.

Brad DeLong stepped up with a more lengthy post: DeLong Smackdown Watch: Dani Rodrik Strikes Back