A certain kind of nerd is excited about this recent speech by Narayana Kocherlakota, the president of the Minneapolis arm of the Federal Reserve. Watching him speak, some people think they saw a leopard not only change its spots, but but paint stripes on as well.

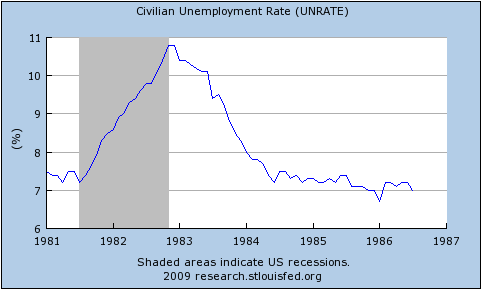

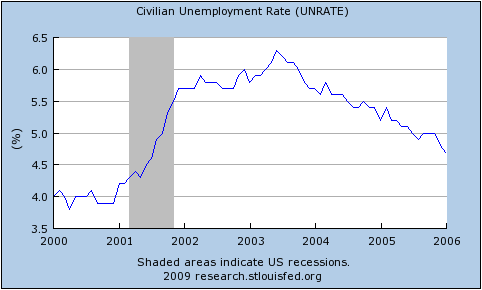

The reason? Well, Kocherlakota is famously an inflation hawk (we do like our animal analogies, don’t we?), but in the speech he argued that the Fed should commit to keeping interest rates at “exceptionally low levels” until unemployment in America falls to 5.5% (it’s currently 8.3% and was last at 5.5% around May 2008) and, as a general rule, inflation hawks are not meant to care about unemployment. They’re meant to focus, like a hawk, on inflation. Here are Bloomberg, Joe Weisenthal, Neil Irwin, FT Alphaville, Felix Salmon, Tim Duy, Scott Sumner, Aki Ito and Brad DeLong (I don’t mean to suggest that these guys are all suggesting that Kocherlakota has become a dove — they’re just all worth reading).

Let’s look at his speech (I’m mixing his words up a little, but the words and their meaning are the same):

As long as longer-term inflation expectations are stable and that the Committee’s medium-term outlook for the annual inflation rate is within a quarter of a percentage point of its target of 2 percent, [the FMOC] should keep the fed funds rate extraordinarily low until the unemployment rate has fallen below 5.5 percent.

This is not the statement that a dove would make. A dove would be speaking about giving weight to both unemployment and inflation in any decision rule. A NGDP-targetter, if forced against their will to speak in this language, would speak of something close to a 50-50 weighting, for example. But that’s not what Kocherlakota is saying here. He is instead saying that the Fed should keep long-term expectations of inflation stable (presumably at 2%) and, in any event, freak out if inflation over the coming year is likely to be any higher than 2.25% and only then, when as an inflation hawk he has nothing to worry about, should the Fed be willing to look at unemployment.

These are still lexicographic preferences. “Fight inflation first and ignore unemployment while you’re doing it,” he is saying. “Then look at unemployment (but be prepared to ditch it if inflation so much as twitches).”

As I say, these are not the ideas of an inflation dove.

It does represent at least a slight shift, though. As Tim Duy makes clear, last year he thought a core PCE inflation rate of 1.5% would be enough to trigger an increase in interest rates, whereas now he appears to be focusing on 2.25% in headline CPI inflation. Those are different objects, though, so it’s not always apples-to-apples.

Instead, I perceive two main shifts in Kocherlakota’s viewpoint:

First, and most importantly, he has been convinced that much of America’s currently-high unemployment is because of deficient demand and not, as he used to hold, because of structural (i.e. supply-side) factors. Here is a snippet from an interview he did with the FT:

“I’m putting less weight on the structural damage story,” said Mr Kocherlakota, arguing that recent research on unemployment pointed more towards “persistent demand shortfalls”. Either way, he said, “the inflation outlook is going to be pretty crucial in telling the difference between the two”.

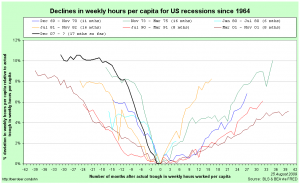

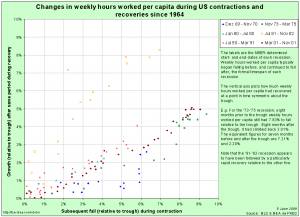

The recent research he mentions, at least in part, will be this paper by Edward Lazear and James Spletzer presented recently at Jackson Hole. Here’s the abstract:

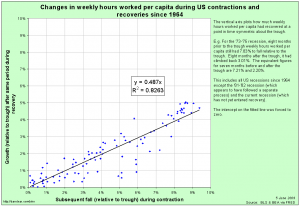

The recession of 2007-09 witnessed high rates of unemployment that have been slow to recede. This has led many to conclude that structural changes have occurred in the labor market and that the economy will not return to the low rates of unemployment that prevailed in the recent past. Is this true? The question is important because central banks may be able to reduce unemployment that is cyclic in nature, but not that which is structural. An analysis of labor market data suggests that there are no structural changes that can explain movements in unemployment rates over recent years. Neither industrial nor demographic shifts nor a mismatch of skills with job vacancies is behind the increased rates of unemployment. Although mismatch increased during the recession, it retreated at the same rate. The patterns observed are consistent with unemployment being caused by cyclic phenomena that are more pronounced during the current recession than in prior recessions.

Second (and to some extent, this is just a corollary of the first), Kocherlakota is now emphasising that conditional on inflation being tightly restrained, he is happy to deploy (almost) any amount of stimulus to help improve the employment situation, whereas previously his emphasis was on how additional stimulus would lead to more inflation.

In other words, I read this speech as evidence that Kocherlakota’s underlying philosophy remains unchanged, but his perception of the problems to which he needs to apply that philosophy has changed. That doesn’t make him a leopard changing it’s spots, that makes him principled, intelligent and open minded.

Naturally, Mark Thoma said all of this before me, and better than I could have.

Update:

Ryan Advent, over at the Economist’s Free Exchange, also has a comment worth reading. He expands a little on the two points I mention:

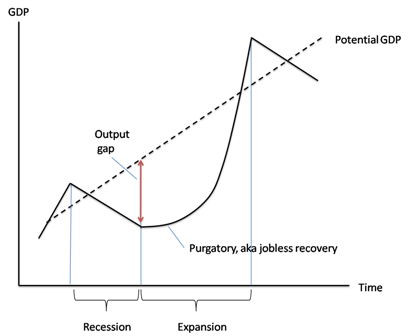

As Mr Kocherlakota points out, one advantage of the threshold approach (an advantage shared by NGDP targeting) is that it allows members to remain agnostic about the extent of structural unemployment in the economy. If unemployment is mostly structural, the inflation threshold will be crossed first; if not, the unemployment threshold will. Either way, the Fed has set its tolerances and adopted a policy to get there.

… which is something that I had originally meant to highlight in this post (honest!). Ryan continues:

(I will point out, however, that the threshold approach implies contracting in the fact of negative structural shocks and easing in the face of positive productivity shocks while NGDP targeting will generally pull in the opposite direction, more sensibly in my view.)

That’s the real debate, right there. Generally everyone agrees on what to do when faced with a demand shock, but how to deal with supply shocks continues to be a matter of considerable disagreement, no doubt to the frustration of both sides. That and how best to disentangle the data to identify whether a shock, or more correctly an assortment of shocks is, on net, mostly supply or mostly demand.