Before I begin: UNICEF has a campaign in the UK at the moment to raise awareness of children being denied their rights around the world. You can see the homepage for the campaign here. You can donate here.

Here are some things to keep in mind when thinking about human rights:

- A right is a particular form of liberty. It is the freedom to do something.

- An obligation or mandate is the opposite of a right. A right involves a conscious choice; thus the phrase “to exercise one’s right.” If there is no choice available, there is no right.

- One person having a right often implies denying another right from a second person. Suppose that you work for me. If I have the right to fire you, you cannot have the right to a guaranteed job with me. If you have the right to go on strike, I cannot have the right to fire you for going on strike.

- Sometimes having a right does not impede the rights of others. A right to make use of a non-rival good is the classic example.

- Exercising a right is not necessarily in a person’s best interest. I have the right to gamble all of my money at a casino, but it probably wouldn’t be wise to do so.

- Every decision of consequence for everybody, everywhere, is subject to a constraint of some kind. There are only 24 hours in a day, the resources at your disposal are finite and, eventually, you will die.

- If a person, operating under a constraint, chooses to not do something, it does not imply that their right has been denied to them.

These last two points, while logical, create problems for many advocacy groups. Consider the woman who, subject to constraints in her finances and the wages on offer for various jobs she can perform, chooses to become a prostitute. Consider the subsistence-farming family that, subject to constraints in it’s finances and the wages on offer for alternative work, chooses to keep it’s children away from school and working on the farm.

It is largely for this reason that many people advocate what they call “economic rights”. Although there are various versions of this (e.g. minimum wages, the welfare state, etc.), you can think of them as a government, on behalf of the entire population, instituting a guaranteed minimum income.

Now, while there are strong moral arguments for such a guarantee (which I fully support and agree with), this is not a right. This is a mandated transfer of income from high-income citizens to low-income citizens. For the rich, it is an obligation (the opposite of a right) and for the poor, it does not directly increase the range of choices available to them. Instead, it indirectly increases that range by relaxing one of their constraints.

I say again: I fully support providing a minimum income to all people by means of a welfare state; nobody should live in poverty. But this is not a right. It is a moral duty. Calling this an “economic right” is a deliberate obfuscation for marketing purposes. People pay more attention and money when a person’s “rights” are being denied than when they simply have a moral obligation to help.

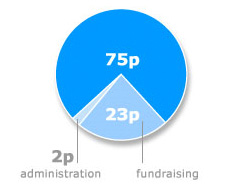

I love the work done by UNICEF. I think they are just about the best NGO on the planet. My wife and I donate money to them. They make an express point of telling you how much of the money you give will go to administration costs or to more fundraising.

I love the work done by UNICEF. I think they are just about the best NGO on the planet. My wife and I donate money to them. They make an express point of telling you how much of the money you give will go to administration costs or to more fundraising.

I just wish they could raise those funds without confusing things by saying that Aklima’s right to education is being denied to her. I recognise that they have to. I just wish that they didn’t.