Victoria Stodden (blog, Harvard page) has an interesting post up on her own blog and that of the Internet & Democracy Group at Harvard based on a recent talk given by Galit Sarfaty on “why no mandate for human rights has been incorporated into the organizational culture at the Bank.”:

She sees the reason as resulting from a clash in ideology between the human rights people, which are largely the lawyers, and economists. Economists dominate the bank, hold most powerful positions, and have a unique and prestigious research group[, while] lawyers are seen as technocrats that aren’t directly involved in projects. The legal department has a culture of secrecy because of this.

Okay, that’s probably true. My question, though, is not over how to get the World Bank to promote human rights but whether they ought to in the first place.

[Sarfaty] suggests three reasons she expects the World Bank to have implemented a human rights policy:

1) peer institutions like UNICEF, UNDP, DFID, have one,

2) the Bank is subject to external pressure by NGOs and internal pressure from employees,

3) even banks in the private sector have human rights frameworks. ICS (the World Bank commercial banking arm) has a human rights framework based on risk management.

These don’t seem like valid reasons to me, as they in essence argue that the World Bank should do something because other organisations are already doing it (the obvious omission is any mention of the IMF). There is also an important difference between merely having a stated policy on human rights and attaching human rights-related conditions to World Bank assistance. I’ll assume that Sarfaty and Stodden are speaking of the latter.

I suspect that this conflict turns on differences of opinion over what “development” actually is and which aspects of development each international organisation ought to seek to promote. It is a truism that nations can develop in a variety of different ways, including economically (both in aggregate and in distribution), socially, politically, educationally, or in public health.

The classic view of the World Bank Group is that its purpose is to promote and assist in economic development. Traditionally, which is to say up to and including much of the 1980s, it focused on aggregate economic development, but more recently it has indirectly expanded into distributive aspects of economic development by promoting and supporting smaller scale, non-infrastructure projects.

It seems to me that while everybody agrees on the importance of educational and public health development, human rights campaigners argue that social and/or political development is at least as important as economic development. Some members of that community go so far as to suggest that improving the social and political lives of people is more important than economic development and that the relative value of economic development has been over played.

I disagree with that last sentence, but I think that few people would disagree with the importance of social and political development in general, although there may some disagreement over what social and political development actually means. To my mind, then, there are two important questions:

a) What are the causal linkages between the different types of development? They clearly all positively reinforce each other, but does one aspect of development have a greater impact on the others?

b) Should a variety of international development bodies each focus on specific aspects of development or should a smaller number of organisations each take a more holistic approach?

I think it’s reasonable to say that the current global system assumes that the answer to (a) is “it’s long been believed that economic development has causal primacy, but this has been recently been brought into question” and that the answer to (b) is “the world cannot agree on the relative importance of each aspect of development, especially since what comprises social and political development is contested, so on a practical level it’s impossible to use a holistic approach.”

The upshot is that we have multilateral organisations to promote different aspects of development separately with the generally perceived legitimacy of each organisation clearly varying with how much international consensus there is on that aspect of development …

- Economic Development: The World Bank Group

- Public Health Development: The World Health Organisation, UNICEF

- Educational Development: UNICEF

- Social and Political Development: The UN Human Rights Council

… and individual governments pursuing unilateral aid programmes in areas of development where there is a conflict of opinion.

The push for the promotion of human rights to be embedded within the World Bank seems to be a change of tack by human rights campaigners after many years of failing to make headway through the extant organisation(s) created to serve their very goals. To cut to the chase, though, the fact that the UNHCR is lambasted as toothless ultimately originates from the fact that the world cannot agree on which human rights ought to be internationally enforceable. This is not just a difference between the “glorious, freedom-loving” West and the “ignoble, oppressive” (ex-)communist countries or the “ignorant, violent” Muslim nations. There are real differences of opinion between the Western nations, too. There are large differences of opinion between the USA and Europe on workers’ rights, for example. There is no guarantee of freedom of speech in Australia. Britain imposes restrictions on public protests within one kilometre of parliament.

So I’m not sure that attaching various human rights requirements to World Bank development loans will ultimately serve to help the situation. Telling Mozambique that it can’t get assistance to build a new port unless it guarantees the rights of its citizens to protest against the government or imposes upper limits to the length of the working day for the port’s employees is hypocritical preaching. It is, in effect, no different to USAID insisting that aid money will only go to HIV/AIDS charities that promote abstinence above all else.

On the other hand, if the purpose of the World Bank group is to promote economic development, it doesn’t seem entirely stupid to promote at least that subset of social and political development that is generally held to assist in economic development. This is where Sarfaty apparently sees a way of introducing the promotion of human rights in general at the Bank:

She concludes that the goal is to frame human rights issues for economists, rather than playing to the perception that it is a political issue. So the idea is to frame human rights goals for economists: presenting empirical data as to how they advance human development and thus is a relevant issue for the Bank and within its poverty eradication mandate.

Even this would be politically difficult, though. Should the people of Yemen be denied new schools if they are unwilling to guarantee that half the students will be girls? It may also lead to some uncomfortable questions for some human rights campaigners. One of the movement’s defining attributes sometimes seems to be one of an all-or-nothing attitude. How would its supporters feel about a piecemeal adoption of human rights promotion by the Bank if the data suggest that one right assists economic development but another does not?

Update (5 April 2008):

Credit where credit is due: My views on this are not entirely my own. They also come from discussions with my wife, Daniela, who is much smarter than me when it comes to this sort of thing.

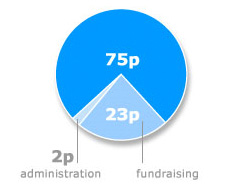

I love the work done by UNICEF. I think they are just about the best NGO on the planet. My wife and I donate money to them. They make an express point of telling you how much of the money you give will go to administration costs or to more fundraising.

I love the work done by UNICEF. I think they are just about the best NGO on the planet. My wife and I donate money to them. They make an express point of telling you how much of the money you give will go to administration costs or to more fundraising.