I hereby present the latest iteration of my telling the world how it ought to be run, damn it. The topic today is:

With (very low) probability, p, event X might occur at location Y, causing offence, harm or even death to a person of type Z.

There are many examples of this sort of scenario. Here are a few:

- X: Fall off a swing

- Y: A public park

- Z: A small child

- X: Trip and fall

- Y: Footpaths (sidewalks) with cracks in the concrete

- Z: Old, clumsy or spatially unaware people

- X: Bringing your dog

- Y: The outside seating area of a cafe

- Z: People that are allergic to, or just have an aversion to, dogs

Here is another, eloquently opposed by M.S. at one of The Economist‘s blogs:

- X: Drown

- Y: Lakes in Massachusetts state parks

- Z: A weak swimmer

I’m sure that you, my eager and most imaginative audience, can describe any number of other examples.

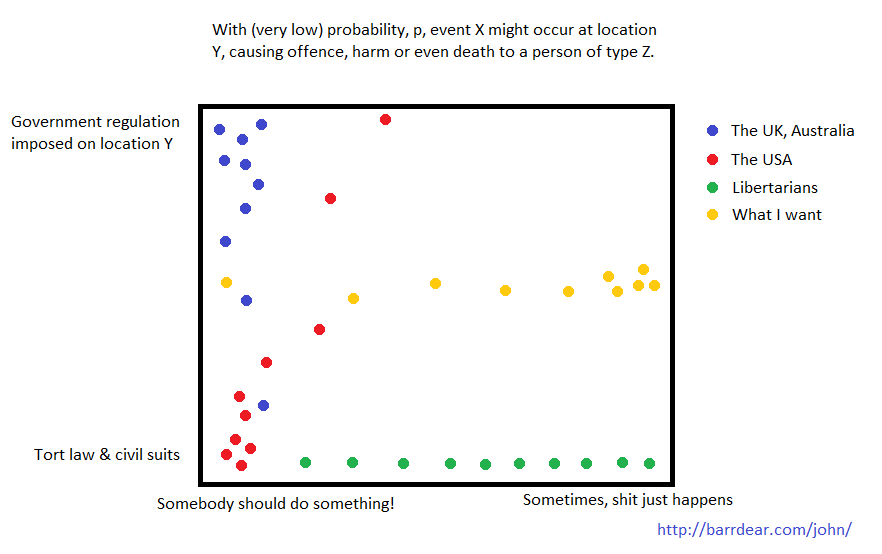

What should we do when confronted with these scenarios? Most people think that the world positions itself along a line separating, at one end, complete government regulation and at the other, zero government regulation and, instead, the use of tort law and civil suits to restrict the “bad” behaviour. This is poor logic, however, because it is overly simplistic; it presupposes that we need to do anything at all!

I favour a midway point between regulation and tort law, but more importantly, to my mind, we usually don’t need to do anything when confronted with these possibilities. Life inherently has risks and, while we should act to avoid exacerbating those risks, we should not necessarily seek to remove them altogether. There are three reasons for this: First, because removing all risk is simply impossible and it is usually the case that reducing risk in one area causes it to rise in another; second, because exposure to some risk is crucial in the development of well-adjusted people and a properly-functioning society; and third, because to restrict people’s choices in order to lower the risk they face is to deprive them of their basic liberty to choose whether to accept that risk for themselves.

Let me summarise my view in this not-even-remotely-to-scale little plot. Think of the horizontal axis as a measure of how easy it is to demonstrate harm to a point of warranting action by “the authorities.”

There are 10 dots of each colour. Broadly speaking, Australia and the UK have chosen the government regulation approach. In Australia, every major political party seems to agree that the “solution” is always more (they would say better) regulation. In the UK, the Lib Dems and Tories make occasional mutterings suggesting that they might agree with me, but for the most part they’re in lock step with Labour (UK), which likes the status quo.

There are 10 dots of each colour. Broadly speaking, Australia and the UK have chosen the government regulation approach. In Australia, every major political party seems to agree that the “solution” is always more (they would say better) regulation. In the UK, the Lib Dems and Tories make occasional mutterings suggesting that they might agree with me, but for the most part they’re in lock step with Labour (UK), which likes the status quo.

America is a bit more varied. By and large, they have adopted the approach of letting tort law and the fear of civil suits induce the effect of (remarkably strict) regulation, but when America does use explicit government regulation, it tends to be something of a light touch. Democrats seem to want to move closer to the British/Australian model, while Republicans seem to either like their status quo or wish to move to the Libertarian ideal.

Small government / Libertarian idealists typically want no government regulation and, to the extent that things need to be dealt with at all, they want everything to happen through the courts. Although they want small government, what government they do want, they want to be strong (e.g. in the enforcement of the law).

Speaking about America, M.S. in the above-linked-to Economist entry writes:

I would gladly join any movement that promised to do away with this sort of nonsense. For example, Philip K. Howard’s organisation “Common Good” (TED talk here) works on precisely this agenda. Common Good’s very bugaboo is useless, wasteful legal interference in schools, health care, recreation, and so on. But what you quickly note with many of these issues is that they’re driven by legal liability concerns. You have a snowblader in Colorado suing a resort because she crashed into someone. You have states declining to put up road-hazard signs because the signs prove they knew the hazard was there, which could render them liable for damages. You have the war on children’s playgrounds. The Massachusetts swimming ban, too, is driven by liability concerns. The park officials in Massachusetts aren’t really trying to minimise the risk that you might drown. They’re trying to minimise the risk that you might sue. The problem here, as Mr Howard says, isn’t simply over-regulation as such. It’s a culture of litigiousness and a refusal to accept personal responsibility. When some of the public behave like children, we all get a nanny state.

Which is exactly what I’m saying about America in my summary, but I think (at least, from my reading) that M.S. is assuming that the opposite of a litigious society is personal responsibility. That’s not true, I’m afraid. The level of personal responsibility is orthogonal to whether your society chooses litigiousness or state regulation.

Nevertheless, I suspect that M.S. (and Matt Yglesis) and I are on the same side in this debate. Let people decide for themselves; they’re adults, or should be. Don’t put a nappy (diaper) on me just because you’re mollycoddling idiot number 8,749 over there.