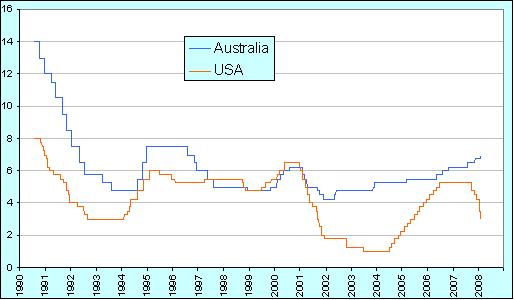

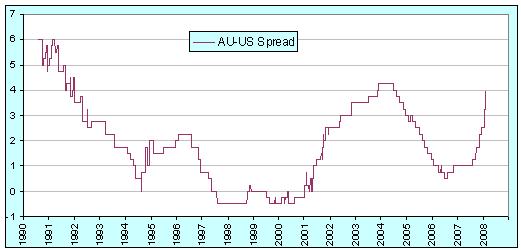

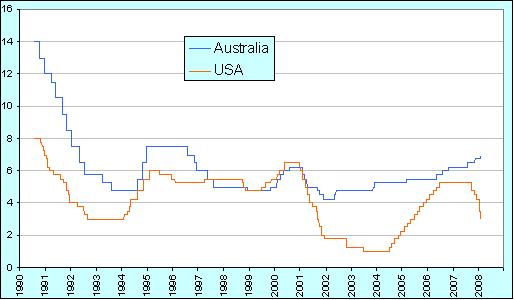

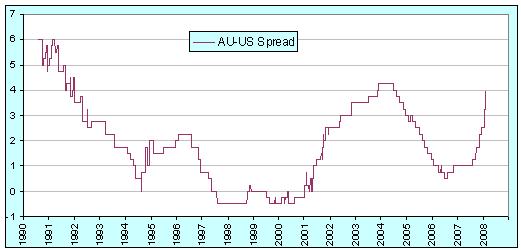

In case anyone is interested, here are graphs of Australia’s and America’s base (cash) target rates and the spread between them.

Source: RBA, Federal Reserve

Research Economist at the Bank of England

In case anyone is interested, here are graphs of Australia’s and America’s base (cash) target rates and the spread between them.

Source: RBA, Federal Reserve

With respect to fiscal policy, I suspect that the stimulus package will help, but believe – like every other political cynic – that the package is being undertaken principally so that candidates in this year’s congressional, senate and presidential elections can be seen to be acting. I am not at all surprised that debate over the precise structure of the package never really rose above the blogosphere, since although that is of enormous significance in how effective it will be, it is of near utter insignificance from the point of view of being seen to act. I find myself agreeing both with Paul Krugman, who points out that only a third of the money will go to people likely to be liquidity-constrained and with Megan McArdle, who (here, here, here, here and here) argues that if you’re going to give aid to the poor of America, doing it via food stamps is, to say the least, less than ideal.

On the topic of monetary policy, I will prefix my thoughts with the following four points:

As I see it, there are three different concerns: whether (and if so, how) monetary policy can help in this scenario; whether the Fed’s actions come with added risks; and whether the timing of the Fed’s actions were appropriate.

First up, we have concerns over whether monetary policy will have any positive effect at all. Paul Krugman (U. Princeton) worries:

Here’s what normally happens in a recession: the Fed cuts rates, housing demand picks up, and the economy recovers. But this time the source of the economy’s problems is a bursting housing bubble. Home prices are still way out of line with fundamentals … how much can the Fed really do to help the economy?

By way of arguing for a a fiscal package, Robert Reich (U.C. Berkley) has a related concern:

[A] Fed rate cut won’t stimulate the economy. That’s because lending institutions, fearing their portfolios are far riskier than they assumed several months ago, won’t lend lots more just because the Fed lowers interest rates. Average consumers are already so deep in debt — record levels of mortgage debt, bank debt, and credit-card debt — they can’t borrow much more, anyway.

Menzie Chinn (U. Wisconsin) looks at these and other worries by going back to the textbook channels through which monetary policy works, concluding:

In answer to the question of which sector can fulfill the role previously filled by housing, I would say the only candidate is net exports. The decline in the Fed Funds rate has led to a depreciation of the dollar. In the future, net exports will be higher than they otherwise would be. However, the behavior of net exports, unlike other components of aggregate demand, depends substantially on what happens in other economies. If policy rates decline in the UK, the euro area, and elsewhere, additional declines of the dollar might not occur. (And as I’ve pointed out before, if rest-of-world GDP growth declines (as seems likely [2]), then net exports might decline even with a weakened dollar).

I think the main point is that the decreases in interest rates, working through the traditional channels, will have a positive impact on components of aggregate demand. With respect to the credit view channels, the impact on lending is going to be quite muted, I think, given the supply of credit is likely to be limited. In fact, I suspect monetary policy will only be mitigating the negative effects of slowing growth and a reduction of perceived asset values working their way through the system.

James Hamilton (U.C. San Diego) is more sanguine, arguing that:

[I]t is hard to imagine that the latest actions by the Fed would fail to have a stimulatory effect.

[A]lthough interest rates respond immediately to the anticipation of any change from the Fed, it takes a considerable amount of time for this to show up in something like new home sales, due to the substantial time lags involved for most people’s home-purchasing decisions … According to the historical correlations, we would expect the biggest effects of the January interest rate cuts to show up in home sales this April.

[The scale of any effect is unknown, though.] Tightening lending standards rather than the interest rate have in my opinion been the biggest explanation for why home sales continued to deteriorate after January 2007 … The effect of rising unemployment and expectations of falling house prices on housing demand is another big and potentially very important unknown.

Going further, Martin Wolf at the FT worries that the Fed may be doing too much, that they the recent cuts in interest rates may serve only to renew or exacerbate the problems that caused the current crisis in the first place.

[P]essimists argue that the combination of declining asset prices (particularly house prices) with household overindebtedness and a fragile banking system means that monetary policy is, in the celebrated words of John Maynard Keynes, like “pushing on a string”. It may not be quite that bad. But, on its own, monetary policy will not act swiftly unless employed on a dramatic scale. The case for fiscal action looks strong.

Yet, in current US circumstances, monetary loosening should have some expansionary effects: it will encourage refinancing of home mortgages; it will weaken the exchange rate, thereby improving net exports; it will, above all, strengthen the health of banking institutions, by giving them cheap government loans.

This brings us to the biggest question: what are the risks? Unfortunately, they are large. One is indefinite continuation of an excessively low rate of US national saving. Others are a loss of confidence in the US currency and much higher inflation.Yet another is a further round of the very asset bubbles and credit expansion that created the present crisis. After all, the financial fragility used to justify current Fed actions is, in large part, the direct result of past Fed efforts at the risk management Mr Mishkin extols.

Moreover, the risks are not just domestic. If the US authorities succeed in reigniting domestic demand, this is likely to reverse the decline in the current account deficit. It will surely reduce the pressure on other countries to change the exchange rate, fiscal, monetary and structural policies that have forced the US to absorb most of the rest of the world’s huge surplus savings.

…

I find it impossible to look at what the US is now trying to do without feeling severely torn. If it succeeds it will renew and, at worst, exacerbate the fragility, both domestic and international, that triggered the turmoil. If it fails, the US and, perhaps, much of the rest of the world could well suffer a prolonged period of economic weakness. This is hardly a pleasant choice. But that it is indeed the choice shows how weakened the world economy and particularly the financial system has become.

In reaction at the FT’s hosted blog, Christopher Carroll (Johns Hopkins U.) argues:

This situation provides a more than sufficient rationale for the Fed’s dramatic actions: Deflation combined with a debt crisis make a toxic combination, because as prices fall, real debt rises. This point was amply illustrated in Japan, where deflation amplified both the number of zombies and the degree of zombification (among the initial stock of the undead). It was also the basis of Irving Fisher’s theory of what made the Great Depression great, and has clear echoes in the macroeconomic literature on the “financial accelerator” pioneered by none other than Ben Bernanke (along with a few other authors who have pursued more respectable careers).

In this context, the risk of an extra year or two of an extra point or two of inflation (if the deflation jitters prove unwarranted and the subprime crisis proves transitory) seems a gamble well worth taking.

Martin Wolf then replied:

[W]hat the Bernanke Fed seems to be trying to halt (with enthusiastic assistance from Congress and the president) is a natural and necessary adjustment, as Ricardo Hausmann argued in the FT on January 31st. I agree that this adjustment must not be too brutal. I agree, too, that both a steep recession and deflation should be avoided. I agree, finally, that market adjustments must not be frozen, as happened in Japan. But I disagree that the US confronts a huge threat of deflation from which the Fed must rescue the economy at all costs. What I fear it is doing, instead, is bailing out the banking system and so trying to reignite the credit cycle, with the consequent dangers of a flight from the dollar, considerably higher inflation and much more bad lending ahead.

Which leaves us with the third concern, over the timing of the rate cuts. The first of them, of 75 basis points, was the largest single cut in a quarter century. The fact that it came from an out-of-schedule meeting makes it almost unprecedented. When we add the fact that the world was in the middle of a broad share sell-off – exacerbated, it turns out, by the winding out of US$75 billion of bets by Societe General – it definitely has the appearance of a panicked decision. Adding the 50bp cut eight days later made for an enormous 1.25 percentage point drop in rates in a fraction over a week.

So what’s my take? Well …

1) The Fed is not as independent as central banks in other countries are. Greg Mankiw may not like it, but the fact is that both Congress and the Whitehouse actively seek to influence monetary policy in the United States. This photograph of Ben Bernanke (chairman of the US Federal Reserve), Christopher Dodd (chairman of the US senate’s banking committee) and Hank Paulson (US Treasury secretary) from mid-August 2007 is typical:

As Martin Wolf noted at the time:

This showed Mr Bernanke as a performer in a political circus. Mr Dodd even announced Mr Bernanke’s policies: the latter had, said Mr Dodd, told him he would use “all the tools ” at his disposal to contain market turmoil and prevent it from damaging the economy. The Fed has its orders: save Main Street and rescue Wall Street. Such panic-driven politicisation is almost certain to lead to both overreaction and the creation of bad precedents.

2) The Fed is mandated to keep both inflation and unemployment low. By comparison, the other major central banks are only required to focus on inflation. When they do look at unemployment, it plays lexicographic second fiddle to keeping inflation in check. At the Fed, they are compelled to take unemployment into account at the same time as looking at inflation.

3) The banking and finance system is central to the real economy. Without a ready supply of credit to worthy and profitable ventures, economic growth would slow dramatically, if not cease altogether. Although it creates a clear moral hazard when bankers’ pay is not aligned with real economic outcomes, this – combined with the first two points – implies that the so-called “Bernanke put” is probably, to some extent, real.

4) The latest GDP numbers and IMF forecasts were released in between the two rate cuts. I have nothing to back this up, but I wouldn’t be the least bit surprised to discover that the Fed gets (or got) a preview of those numbers. Seeing that markets were already tanking, knowing that the reports would send them tumbling further, perhaps believing that they might already be in a recession, almost certainly fearing that the negative news, if released before the Fed had acted, might send risk premia skywards again and recognising that what they needed was a massive cut of at least 100bp, perhaps the Fed concluded that the best policy was to split the cut over two meeting, making a smaller but still unusually large cut before the reports were released to ensure that they didn’t trigger more credit-crunchiness and a second one after in notional “response.”

My point is this: Which would seem more like a panicked response? The way that things did pan out, or a global stock market melt-down that took several more days to settle, followed by the markets being hit with surprisingly negative reports from the IMF on the global economy and the BEA on the US economy, and then a 125 b.p. drop in a single sitting by the Fed?

As I previously mentioned, I got an iPhone for christmas. In the UK, like the USA, Apple arranged an exclusive deal with one mobile provider, in this case O2. The cheapest plan that O2 offered was for £35/month, which included the remarkably low 200 minutes and 200 texts per month, but did also allow for unlimited internet usage when using the O2 network rather than a local 802.11 network.

Perhaps because of the increasing availability of iPhone substitutes, perhaps because of the increasing numbers of jail-broken iPhones that can be used on other networks or perhaps because they know that the new v1.1.3. of the iPhone firmware has already been jailbroken and that when combined with the upcoming release of the iPhone SDK, it’ll stay jailbroken, O2 has recently realised that their time of being a true monopolist has ended. How do I know this? Because this week I received the following text message from O2:

We’re really pleased to tell you that we are upgrading your £35 iPhone tariff in Feb so you will benefit by mid March at the latest.

The new tariff will take your minutes from 200 to 600 and your texts from 200 to 500. Plus you’ll continue to receive the same unlimited UK data allowing you to surf the internet on your iPhone.

Better still, you don’t have to do a thing to get them. We’ll text you to let you know when your new tariff is live.

Simply tap the link to find out more, including details on all our new iPhone tariffs and to see the new tariff terms & conditions.

Which, as a tariff, is much closer to their competitors without the iPhone. For example, Vodafone’s £35/month plan charges £1 for the first 15MB of internet each day and £2 for each additional MB and includes your choice of:

They’ve only dropped down to the usual category of monopolistic competition (they still have pricing power, which they use to implement second-degree price discrimination), but O2’s time of being a complete monopolist has come to an end.

The NY Times looks at economists and the ‘yuck’ factor here.

You can kill a horse to make pet food in California, but not to feed a person. You can hoist a woman over your shoulder while running a 253-meter obstacle course in the Wife-Carrying World Championship in Finland, but you can’t hold a dwarf-tossing contest in France. You can donate a kidney to prevent a death and be hailed as a hero, but if you take any money for your life-saving offer in the United States, you’ll be jailed.

…

Paul Bloom, a professor of psychology at Yale … conducted a two-year study to try to get at why people consider athletes who take steroids to be cheating, but not those who take vitamins or use personal trainers … The only change that caused the interviewed subjects to alter their objections to steroids was when they were told that everyone else thought it was all right. “People have moral intuitions,” Mr. Bloom said. When it comes to accepting or changing the status quo in these situations, he said, they tended to “defer to experts or the community.”

Often introducing money into the exchange – putting it into the marketplace – is what people find repugnant. Mr. Bloom asserted that money is a relatively new invention in human existence and therefore “unnatural.”

Economists are asking the wrong question, Mr. Bloom said[.] They assume that “everything is subject to market pricing unless proven otherwise.”

“The problem is not that economists are unreasonable people, it’s that they’re evil people,” he said. “They work in a different moral universe. The burden of proof is on someone who wants to include” a transaction in the marketplace.

I disagree. Economists are not immoral (violating moral principals), they simply seek to be amoral (not involving questions of right or wrong; without moral quality; neither moral nor immoral).

There is, or ideally is, a permanent distinction in economics between positive statements (statements of fact, shorn of moral interpretation; a statement of what is) and normative statements (moral judgements; a statement of what ought to be). The distinction didn’t originate in economics. We’ve borrowed it from the philosophy department (that economics, like all branches of study, first grew out of). David Hume was using the idea back in 1739, for example.

It’s an enormously powerful technique. It allows us, for example, to observe that there are trade-offs to be balanced in creating optimal tax policy, or that there is a statistically significant correlation between increased rates of abortion and decreased crime rates 20 years later, or that the decision to be a prostitute may be a marginal one instead of a discreet one. These are statements of what is; they are positive statements and can be debated as such. But once a positive statement is agreed upon, it then informs the normative debate.

This is an awkward thing for many non-economists to grasp, because for most of us, our beliefs about facts and beliefs about morals are closely intertwined and even interdependent. None of which is to say that we always can separate the positive from the normative, especially in studying the economics of (government) policy. But even in these cases, attempting to make the separation and acknowledging where any given statement contains an element of the other makes for better, more informed debate.

Canadians celebrated when the Canadian dollar (“the loonie”) hit parity with the U.S. dollar in September last year. At the time, there was some speculation about whether the Australian dollar might follow suit. You’re going to see some more speculation over the next few days. Fundamentals aside, there are two main things that are serving to push the Australian dollar up: the resource boom in Australia and the spread in the interest rates between the two countries, and the latter of those is about to jump.

The US Federal Reserve cut interest rates by 75 basis points a week ago in a surprise, out-of-cycle move. Today they are expected to announce a further cut. Apparently the markets are predicting that there’s an 80% likelihood that it will be a further 50 basis point drop. Next week on the 5th of February, on the back of some truly disastrous inflation figures, the Reserve Bank of Australia will probably raise their rate by 25 basis points. That would be an enormous, 150-point increase in the spread in the space of just two weeks. On that basis, it’s not at all surprising that the markets are already pushing up the AUD.

I graduated from my engineering degree in November of 1998. I already had a job lined up, which I was due to start on the 18th of January, 1999. I had a couple of months to kill and I decided to go on the dole. What I wanted to do was work in a book store, and I applied to some, but not before first applying for unemployment benefits.

The Work for the Dole scheme was up and running by that point, but since it only applied to people who had been receiving payments for over six months, it was never going to be a concern for me. If I remember correctly, I had to fill out a form every two weeks detailing which businesses I had contacted in my quest for work. I definitely remember realising that all I needed to do was open the Yellow Pages at a random page, call whomever my finger fell on and have a conversation like this:

Them: Good afternoon [I was an unemployed recently-ex-student, after all. You can’t expect me to get out of bed in the morning, can you?]. This is company XYZ. How may I help?

Me: Hi. Do you have any jobs going?

Them: Uhh, no.

Me: Okay. Thanks.

I could then list that company on my fortnightly form, safe in the knowledge that even if Centrelink did bother to check – and I seriously doubt that they ever did; I could have written that I applied to “Savage Henry’s discount rabbit stranglers” and they would have just filed it away – then I was covered.

That felt a bit too much like taking the piss though, so I made sure that my targets were legitimate. As I mentioned above, I mostly applied to book and map retailers. I never lied to Centrelink or to any of the places I applied to. I always admitted to everyone that I had a job lined up and only needed to fill in the two-month gap, but if the truth be told, I didn’t put much effort in either, except for a couple of early applications to places where I genuinely would have enjoyed working. It’s not that I was disheartened; just that I didn’t particularly care. I wasn’t desperate for the cash (although it was certainly handy) or a job (since I’d have to quit in a few weeks anyway). I was really only doing the dole thing to see what it was like and the answer was: boring, but easy.

I’ve never felt any guilt or shame at doing it and I don’t think that any of my friends at the time were judging me negatively for it. It was a little unorthodox, but just accepted. I’ve certainly paid a lot more in taxes since than I received on the dole or for my university education. Fast-forward to 2008 and I am thinking about the social acceptability of receiving welfare payments, both in Australia and abroad.

It may just be the stereotype, but I get the feeling that in continental Europe, both in 1998 and today, what I did would barely raise an eyebrow; that it would be completely accepted. In the U.S.A., on the other hand, I think that it would be regarded by many as a shameful thing to do and an abuse of federal money. In Australia and the UK, I’m not so sure. I suspect that the more “aspirant middle class” you are and the older you are, the more shameful it will seem. I have no idea if the age thing is because it’s a process that everybody goes through as they get older or if there’s been a genuine generational shift in attitudes.

Any thoughts?

One of the most important ideas in economics is that people think and act on the margin. By that I mean that we make our decisions as if we were looking at the costs and benefits of just one more. Just one more slice of pizza. Just one more minute on the bike in the gym. Just one more share of some stock bought. If we reckon the benefits of that one more to be greater than the cost of it, irrespective of what has come before and what may come after, we’ll typically do it. The point is that we optimise, or at least act as though we optimise. We may only optimise locally instead of globally (that last slice of pizza may have seemed like a good idea at the time, but it’s not much good for my health in general), but it’s still what we do.

The idea is by no means unique to economics. There is, at the least, an entire branch of mathematics devoted to it. But economists just love to point out that optimisation – and, therefore, thinking on the margin – applies to human behaviour just as well as it does to equations on a blackboard, and that realisation can sometimes lead to surprising, even counter-intuitive observations with serious consequences for public policy.

As I’ve mentioned before (here and here), Steven Levitt and Sudhir Venkatesh are currently finishing a paper on street prostitution in Chicago. They were able to study the provision of prostitution services during a predictable demand shock and discovered that the supply of prostitution services is rather elastic: a 63% increase in quantity was associated with only a 30% increase in price. More importantly, that increase came on three margins: an increase in supply from existing prostitutes (who, on average, only work 13 hours a week), a temporary in-migration of prostitutes from other areas and the temporary entry into the market of women who are not ordinarily willing to perform sex acts for money. Levitt and Venkatesh estimate that 43 of the 63% increase in the number of tricks came from existing prostitutes in the area and the remaining 20 from the in-migrating prostitutes and the temporary market entrants.

That third margin bears highlighting. Typical thinking about the topic holds that the choice to become a prostitute, if it is a choice at all, is a discrete [update: I originally had “discreet”. It’s certainly that 🙂] one; that women and a very few men first choose – or are compelled – to be a prostitute and only then consider what money they might make. The idea that some women might choose to start or stop being a prostitute in the face of a ten, five or even one dollar an hour change in the money available doesn’t make sense in this thinking. I believe that the reason for this is founded in a moral abhorrence at the very idea of prostitution – the belief that in addition to any social or economic conditions faced by prostitutes, the act of prostitution itself is immoral. Since it has become au fait, among Western intelligentsia at least, to never accuse people of direct moral failure, it has also become the norm to conclude that all prostitutes were misled or forced into their position and thus need to be rescued. The terrible issue of people trafficking naturally lends support to this idea.

I do not want to belittle the tragedy and travesty that is people trafficking. It is a truly awful phenomenon and the fact that it exists at all, let alone in countries that are supposed to be based on freedom of the individual as a founding tenet, is abhorrent. It needs to be stamped out.

My concern is to highlight that not all prostitutes are forced into their profession. There really are women who, faced with an outside option of $7/hour, are not willing to be a prostitute for $25/hour, but are willing to do so for $35/hour. I have no doubt at all that – and this is important – the same statement would be true if you multiplied all of those figures by 10.

The upshot of this is that, slaves aside (and that’s what people trafficking is – slave trading), you cannot simply save or rescue a prostitute. It is not a problem, if you consider it one, to be tackled. It is not something that you solve, once and for all. Prostitutes are people like everyone else and like everyone else, they think on the margin and respond to incentives. If your concern is that prostitutes live in poverty, that they are compelled into their work by economic hardship, then you must work to improve their outside options. But at the same time, you should recognise that you will not be stopping prostitution from happening; you will simply be raising the minimum asking price. That will lower the quantity demanded, but it will never remove it altogether.

Update (5 April 2008):

See my new entry here. It would appear that maybe even the figures for human trafficking are overblown.

I’ve been meaning to read this piece by Martin Wolf (chief economics commentator for the Financial Times) for the last week. As it happens, it’s a “me too” response and a minor expansion to this brilliant piece by Raghuram Rajan (professor of finance at the Graduate School of Business at the University of Chicago and former chief economist at the IMF). I recommend reading both of them in full. Here are some cut-down snippets from Rajan’s efforts:

The typical manager of financial assets generates returns based on the systematic risk he takes – the so-called beta risk – and the value his abilities contribute to the investment process – his so-called alpha.

…

[T]here are only a few sources of alpha for investment managers. One of them comes from having truly special abilities in identifying undervalued financial assets. [e.g. Warren Buffet]

…

A second source of alpha is from … using financial resources to create, or obtain control over, real assets and to use that control to change the payout obtained on the financial investment. [e.g. a venture capitalist]

…

A third source of alpha is financial entrepreneurship or engineering – creating securities or cash flow streams that appeal to particular investors or tastes. As long as the investment manager does not create securities that exploit investor weaknesses or ignorance (and there is unfortunately too much of that), this sort of alpha is also beneficial, but it requires constant innovation.

…

How do untalented investment managers justify their pay? Unfortunately, all too often it is by creating fake alpha – appearing to create excess returns but in fact taking on hidden tail risks, which produce a steady positive return most of the time as compensation for a rare, very negative, return.

…

True alpha can be measured only in the long run and with the benefit of hindsight – in the same way as the acumen of someone writing earthquake insurance can be measured only over a period long enough for earthquakes to have occurred. Compensation structures that reward managers annually for profits, but do not claw these rewards back when losses materialise, encourage the creation of fake alpha. Significant portions of compensation should be held in escrow to be paid only long after the activities that generated that compensation occur.

Martin Wolf’s addition comes in like this:

By paying huge bonuses on the basis of short-term performance in a system in which negative bonuses are impossible, banks create gigantic incentives to disguise risk-taking as value-creation.

We would be better off with Jupiter’s 12-year “year”, since it takes about that long to know how profitable strategies have been. The point is that a year is an astronomical, not an economic, phenomenon (as it once was, when harvests were decisive). So we must ensure that a substantial part of pay is better aligned to the realities of the business: that is, is made in restricted stock redeemable over a run of years (ideally, as many as 10).

Yet individual institutions cannot change their systems of remuneration on their own, without losing talented staff to the competition. So regulators may have to step in. The idea of such official intervention is horrible, but the alternative of endlessly repeated crises is even worse.

Dani Rodrik has been noting for a while that Martin Wolf seems to be coming ’round to his point of view in economic development. I’ve seen the same thing and it’s great to see.

Today I sat down with my supervisor, Professor Andrea Prat, to talk some more about my research ideas. I would have liked to speak with him more frequently over this year, but it turns out that teaching is taking more time than I anticipated, just as everyone warned me it would.

My ideas are a lot more fleshed-out than the vague arm-waving on my research page and Prof. Prat seemed excited at where they are going. That’s big in itself – when one of my friends here at LSE heard that he was going to be my supervisor he replied with: “Wow. He must have an IQ of, like, a million.” Not having great, gaping holes shot in my thoughts is a minor victory in itself. 🙂

I wasn’t planning on developing it fully for my research paper this year, but even on the area that I was thinking of doing, his unnerving comment was that it is probably still a bit too big an idea for this year.

Bugger.

We’re covering this in my EC102 classes this week and I thought it interesting enough to share with a wider audience:

Looking at what goes into GDP is usually a pretty tedious affair, but the simplest way to think of it is like this: GDP is meant to represent the total value added. It is new work done; new stuff produced.

One upshot of this is that new houses are counted in GDP, while sales of existing houses are not. This is because sales of existing houses are just value transferred – an exchange of assets – and so don’t represent new effort. That’s not quite true. The real-estate agent fees and legal fees associated with the sale count, since they are new work done: they add new value by facilitating the trade.

Here’s a trick in looking at value added: we only need to look at the prices of final goods. This is because the price of the final good will represent the total value added along the entire production chain. The typical example of this used in introductory textbooks is bread:

| Who | Sells | Price | Value added |

| Farmer | Wheat | $0.10 | $0.10 |

| Miller | Flour | $0.20 | $0.10 |

| Baker | Bread | $0.45 | $0.15 |

| Supermarket | Packaged and convenient bread | $1.00 | $0.55 |

Now consider a country that has a large natural resource sector. Australia is a great example. So are all the oil exporting countries. We’ll pick the mining of iron ore in Australia as an example. Just like with the wheat above, there is a whole range of production possibilities based on the iron ore. However, when it’s exported, the final good that gets counted from the point of view of the Australian economy is the iron ore in the ship as it sails off to another country.The mining companies are definitely adding value. They’ve got to find the stuff in the first place, dig it up, clean it a bit to get rid of the dirt, transport it to the coast and then ship it overseas. They’ve also got to maintain all their equipment and allow for the fact that they wear out over time. All of that is new effort. But the price that India or China pays for the ore is more than cost of doing all of that. A large fraction of the price they pay represents the market value of the underlying asset – the ore – itself. But since the mining company didn’t actually produce the ore, that part of the price shouldn’t really count in GDP, for the same reason that when existing houses are sold, only the agent and legal fees are counted. None of this is really news.

When natural-resource-based industries are only a small part of a country’s economy, there’s not too much distortion, so we tend not to worry about it. But when those industries represent a large share of the national income, then the overestimates can be significant. In Australia, mining represents about 6.7% of the national economy. A fair chunk of that will be “true” value added, but a large share of it is really just the transfer of assets. How much? Well, BHP currently has a Return on Equity of 49%, while the long-run, risk-free return on capital is more like 8-10%. So as a very rough guess, assuming that BHP is representative of the mining industry as a whole and that the mining industry is competitive, we might suggest that Australia’s “true” GDP is at least 39% * 6.7% = 2.6% smaller than we think it is.

Some people might at this point wonder about the farmer back in the bread example. What if the farmer who, like BHP, is taking something from the land, is actually only adding 60% of the value that we think she is? The answer lies in the fact that there is a large production chain that builds up from the farmer’s wheat. Even if we remove a large fraction of the farmer’s value-added, that is only a small share of the total value added that we see in the final good’s price. So we would expect this overestimate to be very small overall. The point about mining is that we are only adding a small amount of value relative to that of the asset we are trading away, so as a percentage of the final good, the asset itself is quite large.