With respect to fiscal policy, I suspect that the stimulus package will help, but believe – like every other political cynic – that the package is being undertaken principally so that candidates in this year’s congressional, senate and presidential elections can be seen to be acting. I am not at all surprised that debate over the precise structure of the package never really rose above the blogosphere, since although that is of enormous significance in how effective it will be, it is of near utter insignificance from the point of view of being seen to act. I find myself agreeing both with Paul Krugman, who points out that only a third of the money will go to people likely to be liquidity-constrained and with Megan McArdle, who (here, here, here, here and here) argues that if you’re going to give aid to the poor of America, doing it via food stamps is, to say the least, less than ideal.

On the topic of monetary policy, I will prefix my thoughts with the following four points:

- The decision makers at the US Federal Reserve are almost certainly smarter than I am (or, indeed, my audience is)

- They certainly have more experience than I do

- They certainly put more effort into thinking about this stuff than I do

- They certainly have access to more timely and higher quality data than I do

As I see it, there are three different concerns: whether (and if so, how) monetary policy can help in this scenario; whether the Fed’s actions come with added risks; and whether the timing of the Fed’s actions were appropriate.

First up, we have concerns over whether monetary policy will have any positive effect at all. Paul Krugman (U. Princeton) worries:

Here’s what normally happens in a recession: the Fed cuts rates, housing demand picks up, and the economy recovers. But this time the source of the economy’s problems is a bursting housing bubble. Home prices are still way out of line with fundamentals … how much can the Fed really do to help the economy?

By way of arguing for a a fiscal package, Robert Reich (U.C. Berkley) has a related concern:

[A] Fed rate cut won’t stimulate the economy. That’s because lending institutions, fearing their portfolios are far riskier than they assumed several months ago, won’t lend lots more just because the Fed lowers interest rates. Average consumers are already so deep in debt — record levels of mortgage debt, bank debt, and credit-card debt — they can’t borrow much more, anyway.

Menzie Chinn (U. Wisconsin) looks at these and other worries by going back to the textbook channels through which monetary policy works, concluding:

In answer to the question of which sector can fulfill the role previously filled by housing, I would say the only candidate is net exports. The decline in the Fed Funds rate has led to a depreciation of the dollar. In the future, net exports will be higher than they otherwise would be. However, the behavior of net exports, unlike other components of aggregate demand, depends substantially on what happens in other economies. If policy rates decline in the UK, the euro area, and elsewhere, additional declines of the dollar might not occur. (And as I’ve pointed out before, if rest-of-world GDP growth declines (as seems likely [2]), then net exports might decline even with a weakened dollar).

I think the main point is that the decreases in interest rates, working through the traditional channels, will have a positive impact on components of aggregate demand. With respect to the credit view channels, the impact on lending is going to be quite muted, I think, given the supply of credit is likely to be limited. In fact, I suspect monetary policy will only be mitigating the negative effects of slowing growth and a reduction of perceived asset values working their way through the system.

James Hamilton (U.C. San Diego) is more sanguine, arguing that:

[I]t is hard to imagine that the latest actions by the Fed would fail to have a stimulatory effect.

[A]lthough interest rates respond immediately to the anticipation of any change from the Fed, it takes a considerable amount of time for this to show up in something like new home sales, due to the substantial time lags involved for most people’s home-purchasing decisions … According to the historical correlations, we would expect the biggest effects of the January interest rate cuts to show up in home sales this April.

[The scale of any effect is unknown, though.] Tightening lending standards rather than the interest rate have in my opinion been the biggest explanation for why home sales continued to deteriorate after January 2007 … The effect of rising unemployment and expectations of falling house prices on housing demand is another big and potentially very important unknown.

Going further, Martin Wolf at the FT worries that the Fed may be doing too much, that they the recent cuts in interest rates may serve only to renew or exacerbate the problems that caused the current crisis in the first place.

[P]essimists argue that the combination of declining asset prices (particularly house prices) with household overindebtedness and a fragile banking system means that monetary policy is, in the celebrated words of John Maynard Keynes, like “pushing on a string”. It may not be quite that bad. But, on its own, monetary policy will not act swiftly unless employed on a dramatic scale. The case for fiscal action looks strong.

Yet, in current US circumstances, monetary loosening should have some expansionary effects: it will encourage refinancing of home mortgages; it will weaken the exchange rate, thereby improving net exports; it will, above all, strengthen the health of banking institutions, by giving them cheap government loans.

This brings us to the biggest question: what are the risks? Unfortunately, they are large. One is indefinite continuation of an excessively low rate of US national saving. Others are a loss of confidence in the US currency and much higher inflation.Yet another is a further round of the very asset bubbles and credit expansion that created the present crisis. After all, the financial fragility used to justify current Fed actions is, in large part, the direct result of past Fed efforts at the risk management Mr Mishkin extols.

Moreover, the risks are not just domestic. If the US authorities succeed in reigniting domestic demand, this is likely to reverse the decline in the current account deficit. It will surely reduce the pressure on other countries to change the exchange rate, fiscal, monetary and structural policies that have forced the US to absorb most of the rest of the world’s huge surplus savings.

…

I find it impossible to look at what the US is now trying to do without feeling severely torn. If it succeeds it will renew and, at worst, exacerbate the fragility, both domestic and international, that triggered the turmoil. If it fails, the US and, perhaps, much of the rest of the world could well suffer a prolonged period of economic weakness. This is hardly a pleasant choice. But that it is indeed the choice shows how weakened the world economy and particularly the financial system has become.

In reaction at the FT’s hosted blog, Christopher Carroll (Johns Hopkins U.) argues:

This situation provides a more than sufficient rationale for the Fed’s dramatic actions: Deflation combined with a debt crisis make a toxic combination, because as prices fall, real debt rises. This point was amply illustrated in Japan, where deflation amplified both the number of zombies and the degree of zombification (among the initial stock of the undead). It was also the basis of Irving Fisher’s theory of what made the Great Depression great, and has clear echoes in the macroeconomic literature on the “financial accelerator” pioneered by none other than Ben Bernanke (along with a few other authors who have pursued more respectable careers).

In this context, the risk of an extra year or two of an extra point or two of inflation (if the deflation jitters prove unwarranted and the subprime crisis proves transitory) seems a gamble well worth taking.

Martin Wolf then replied:

[W]hat the Bernanke Fed seems to be trying to halt (with enthusiastic assistance from Congress and the president) is a natural and necessary adjustment, as Ricardo Hausmann argued in the FT on January 31st. I agree that this adjustment must not be too brutal. I agree, too, that both a steep recession and deflation should be avoided. I agree, finally, that market adjustments must not be frozen, as happened in Japan. But I disagree that the US confronts a huge threat of deflation from which the Fed must rescue the economy at all costs. What I fear it is doing, instead, is bailing out the banking system and so trying to reignite the credit cycle, with the consequent dangers of a flight from the dollar, considerably higher inflation and much more bad lending ahead.

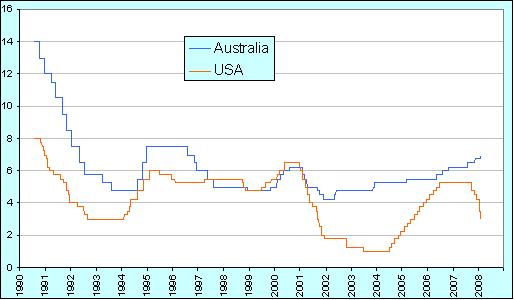

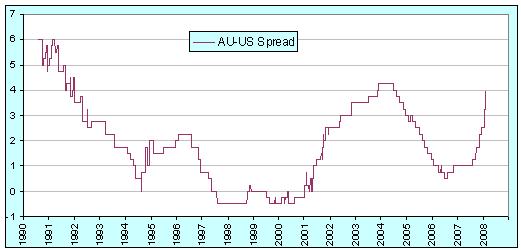

Which leaves us with the third concern, over the timing of the rate cuts. The first of them, of 75 basis points, was the largest single cut in a quarter century. The fact that it came from an out-of-schedule meeting makes it almost unprecedented. When we add the fact that the world was in the middle of a broad share sell-off – exacerbated, it turns out, by the winding out of US$75 billion of bets by Societe General – it definitely has the appearance of a panicked decision. Adding the 50bp cut eight days later made for an enormous 1.25 percentage point drop in rates in a fraction over a week.

So what’s my take? Well …

1) The Fed is not as independent as central banks in other countries are. Greg Mankiw may not like it, but the fact is that both Congress and the Whitehouse actively seek to influence monetary policy in the United States. This photograph of Ben Bernanke (chairman of the US Federal Reserve), Christopher Dodd (chairman of the US senate’s banking committee) and Hank Paulson (US Treasury secretary) from mid-August 2007 is typical:

As Martin Wolf noted at the time:

This showed Mr Bernanke as a performer in a political circus. Mr Dodd even announced Mr Bernanke’s policies: the latter had, said Mr Dodd, told him he would use “all the tools ” at his disposal to contain market turmoil and prevent it from damaging the economy. The Fed has its orders: save Main Street and rescue Wall Street. Such panic-driven politicisation is almost certain to lead to both overreaction and the creation of bad precedents.

2) The Fed is mandated to keep both inflation and unemployment low. By comparison, the other major central banks are only required to focus on inflation. When they do look at unemployment, it plays lexicographic second fiddle to keeping inflation in check. At the Fed, they are compelled to take unemployment into account at the same time as looking at inflation.

3) The banking and finance system is central to the real economy. Without a ready supply of credit to worthy and profitable ventures, economic growth would slow dramatically, if not cease altogether. Although it creates a clear moral hazard when bankers’ pay is not aligned with real economic outcomes, this – combined with the first two points – implies that the so-called “Bernanke put” is probably, to some extent, real.

4) The latest GDP numbers and IMF forecasts were released in between the two rate cuts. I have nothing to back this up, but I wouldn’t be the least bit surprised to discover that the Fed gets (or got) a preview of those numbers. Seeing that markets were already tanking, knowing that the reports would send them tumbling further, perhaps believing that they might already be in a recession, almost certainly fearing that the negative news, if released before the Fed had acted, might send risk premia skywards again and recognising that what they needed was a massive cut of at least 100bp, perhaps the Fed concluded that the best policy was to split the cut over two meeting, making a smaller but still unusually large cut before the reports were released to ensure that they didn’t trigger more credit-crunchiness and a second one after in notional “response.”

My point is this: Which would seem more like a panicked response? The way that things did pan out, or a global stock market melt-down that took several more days to settle, followed by the markets being hit with surprisingly negative reports from the IMF on the global economy and the BEA on the US economy, and then a 125 b.p. drop in a single sitting by the Fed?