This is a fascinating time to be thinking about monetary policy…

Like everybody else, central banks can do two things: they can talk, or they can act.

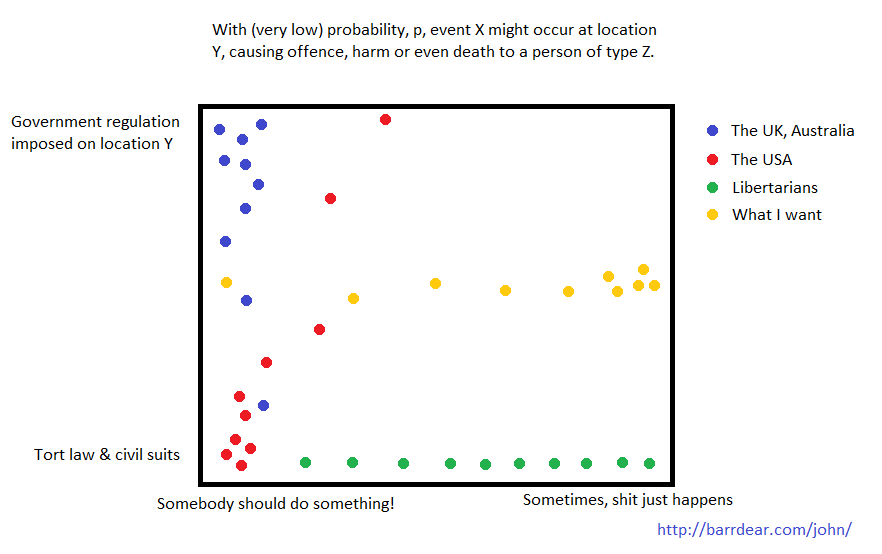

Some people say that talk is cheap and, in any event, discretion implies bias.

Other people point out that things like central bankers’ concern for their reputation mean that it’s perfectly possible to promise today to implement history-dependent policy tomorrow. Some cheeky people like to point out that this amounts to saying that, when in a slump, a central bank should “credibly commit to being irresponsible” in the future.

In fact, some people argue (pdf) that, in my words, “all monetary policy is, fundamentally, about expectations of the future.” But if that’s the case, why act at all? Why not just talk and stay away from being a distorting influence in the markets?

There are two reasons: First, since since talk is cheap, credibility requires that people know that you can and, if necessary, will act to back it up (talk softly and carry a big stick). Second, because if you can convince people with actions today, you don’t need to explicitly tell them what your policy rule will be tomorrow and central bankers love discretion because no rule can ever capture what to do in every situation and well, hey … a sense of mystery is sexy.

OMO stands for “Open Market Operation”. It’s how a central bank acts. Some scallywags like to say that when a central bank talks, it’s an “Open Mouth Operation.” Where it gets fun (i.e. complicated) is that often a central bank’s action can be just a statement if the stick they’re carrying to back it up is big enough.

In regular times, a typical central bank action will be to announce an interest rate and a narrow band on either side of it. In theory, it could be any interest rate at all, but in practice they choose the interest rate for overnight loans between banks. They then commit to accepting in or lending out infinite amounts of money if the interest rate leaves that narrow band. Infinity is a very big stick indeed, so people go along with them.

So what should a central bank do when overnight interest rates are at (or close to) zero and the central bank doesn’t want to take them lower, but more stimulus is needed?

Woodford-ites say that you’ve got to commit, baby. Drop down to one knee, look up into the economy’s eye and give the speech of your life. Tell ’em what you promise to do tomorrow. Tell ’em that you’ll never cheat. Pinky-swear it … and pray that they believe you.

Monetarists, on the other hand, cough politely and point out that the interest rate on overnight inter-bank loans is just a price and there are plenty of other prices out there. The choice of the overnight rate was an arbitrary one to start with, so arbitrarily pick another one!

Of course, the overnight rate wasn’t chosen arbitrarily. It was chosen because it’s the price that is the furthest away from the real economy and, generally speaking, central bankers hate the idea of being involved in the real economy almost as much as they love discretion. They watch it, of course. They’re obsessed by it. They’re guided by it and, by definition, they’re trying to influence it, but they don’t want to be directly involved. A cynic might say that they just don’t want to get their hands dirty, but a realist would point out that no matter the pain and joy involved in individual decisions in the economy, a cool head and an air of abstraction are needed for policy work and, in any event, a central banker is hardly an industrialist and is therefore entirely unqualified to make decisions at the coalface.

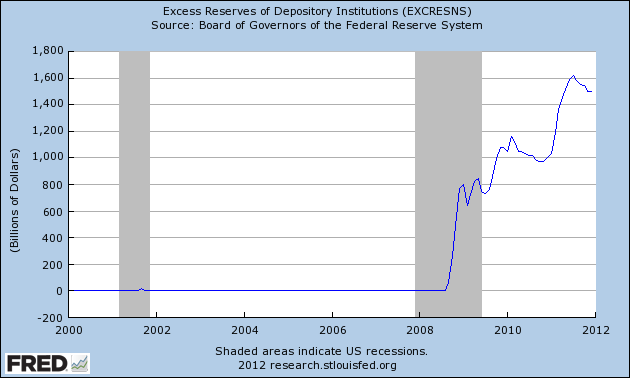

But as every single person knows, commitment is scary, even when you want it, so the whole monetarist thing is tempting. Quantitative Easing (QE) is a step along that monetarist approach, but the way it’s been done is different to the way that OMOs usually work. There has been no target price announced and while the quantities involved have been big (even huge), they have most definitely been finite. The result? Well, it’s impossible to really tell because we don’t know how bad things would have been without the QE. But it certainly doesn’t feel like a recovery.

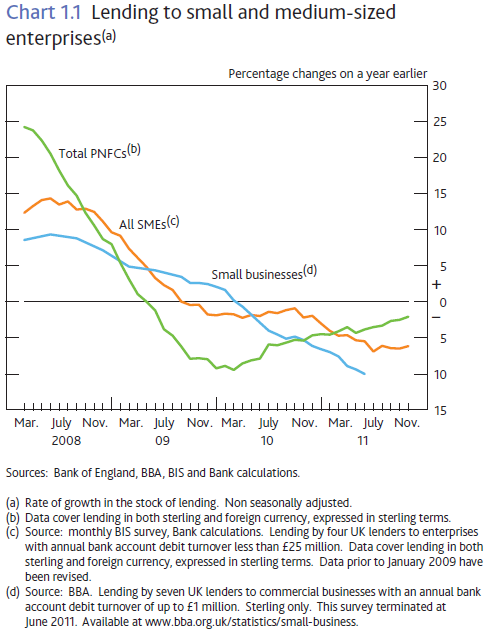

Some transmission-mechanism plumbers think that the pipes are clogged (see also me).

Woodford-ites say that it’s because there’s no love, baby. Where’s the commitment?

Monetarists say that infinity is fundamentally different to just a really big number.

Market monetarists, on the other hand (yes, I’m sure you were wondering when I’d get to them), like to argue that the truth lies in between those last two. They say that it’s all about commitment (and without commitment it’s all worthless), but sometimes you need an infinitely big stick to convince people. They generally don’t get worked up about how close the central bank’s actions are to the real economy and they’re not particularly bothered with concrete steps.

So now we’ve got some really interesting stuff going on:

The Swiss National Bank (a year ago) announced a price and is continuing to deploy the power of infinity.

The European Central Bank has switched to infinity, but is not giving a price and is not giving any forward guidance.

The Federal Reserve has switched to infinity and is giving some forward guidance on their policy decision rule.

The Bank of England is trying to fix the plumbing.

It really is a fascinating time to be thinking about this stuff.