Via Matthew Ylesias, I came across this piece by Chris Bowers: “Now Is Not The Time To Count Super Delegates”

Right now, with the exception of NBC news, most news outlets are counting super delegates in their running delegate total for the Democratic nomination … From 1984 to 2004, the overwhelming majority of super delegates have cast their convention votes for the candidate who won more votes during the primary and caucus season. This was just as true for Mondale in 1984 as it was for Kerry in 2004. On every single occasion, large numbers of super delegates switched their early, public support for a candidate in favor of the candidate who had the most popular support from voters in Democratic primaries and participants in Democratic caucuses.

This is important stuff. For the 2008 nomination, the Democratic Party will have 3,253 pledged delegates at their August convention and 796 unpledged (or “super”) delegates. If the super-delegates break 90-10 for the winner among pledged delegates, a 1,627 vs. 1,626 split in the pledged delegates would end up as a 2,343 vs. 1,706 vote at the convention and so look like a blow-out for the winner.

Why do they do it? Because they want the public to see the Democratic Party lining up behind a clear candidate. A bitter, narrow fight on the convention floor looks like a divided party that cannot come together and lead, whereas a large win looks like momentum and inevitability. It’s also important to note that, by and large, the super-delegates are up for re-election themselves. From Wikipedia: “In 2008, the superdelegates include 221 members of the U.S. House of Representatives, 48 senators, including the District of Columbia’s two shadow senators, 31 state and territorial governors, 397 members of the Democratic National Committee, 23 distinguished party leaders, and 76 others.” Nobody wants to be running for re-election as the guy or girl who voted against their own presidential candidate.

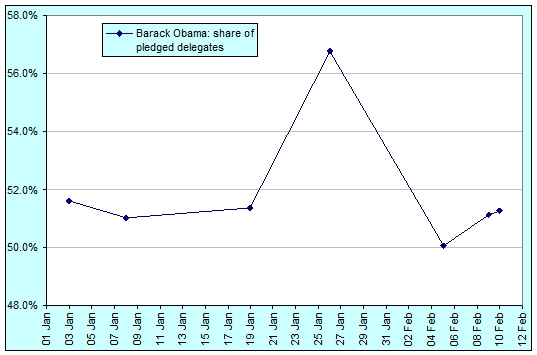

Given all that, I thought I’d have a look at how Mr. Obama and Mrs. Clinton have being going in just the pledged delegates. The data below comes mostly from CNN. Some of the counts are still just estimates. Note that I am ignoring the delegates awarded to John Edwards.

| Date | Barack Obama: running total | Barack Obama: fraction of pledged delegates | Hillary Clinton: running total | Hillary Clinton: fraction of pledged delegates |

| 3 Jan | 16 | 51.6% | 15 | 48.4% |

| 8 Jan | 25 | 51.0% | 24 | 49.0% |

| 19 Jan | 38 | 51.4% | 36 | 48.6% |

| 26 Jan | 63 | 56.8% | 48 | 43.2% |

| 5 Feb | 901 | 50.1% | 899 | 49.9% |

| 9 Feb | 987 | 51.1% | 944 | 48.9% |

| 10 Feb | 1002 | 51.3% | 953 | 48.7% |

In the lead up to super (dooper) Tuesday on the 5th of February, Hillary Clinton had to temporarily stump up US$5 million of her own money. Following the Maine caucus on the 10th of February, she changed her campaign manager. On the 12th of February, the states of Maryland and Virginia and the District of Columbia will vote in their primaries and the Democrats Abroad will finish taking its votes (they started on the 5th of Feb). The polls have Obama clearly in front in Maryland (by 21 points on average) and Virginia (by 17 points on average). The betting markets estimate his chances of winning in Maryland and Virginia at 97.7% and 96.0% respectively. On the 19th of February, Hawaii (where Obama was born) will have its caucus and Wisconsin will have its primary.

It’s not until Texas, Rhode Island, Vermont and Ohio on the 4th of March that pundits are predicting the next win for Hillary, but there’s no guarantee that she’ll win enough to get in front.

Perhaps the “coming from behind” story is wrong. Perhaps Barack Obama has been in front every step of the way in 2008.