Via Economix, here’s an OECD study of working hours by citizens of it’s member countries. Here’s the relevant graph:

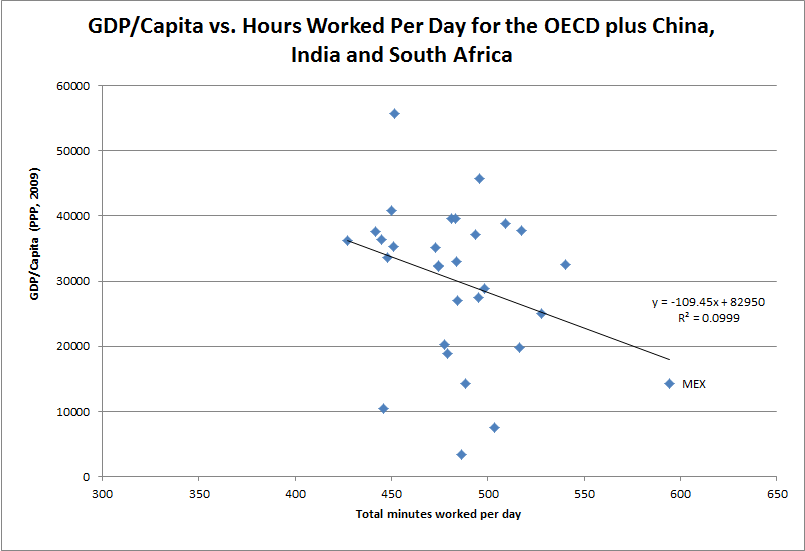

Much of it is as you’d expect from cultural stereotypes — Western Europe working the least, Japan and Mexico working the most — but I was a little surprised that Australia isn’t above average. What’s striking — to me, at least — is that hours worked per day doesn’t seem to be a particularly good predictor of income per capita. In fact, it’s interesting enough that I pulled the GDP per capita data from the OECD to do up a scatter plot:

There’s not much of a relationship at all (R-squared of 0.1) and to the extent that there is one, it’s negative — working more per day is associated with a lower income per capita. Without Mexico (on the bottom-right), the R-squared drops to 0.04.

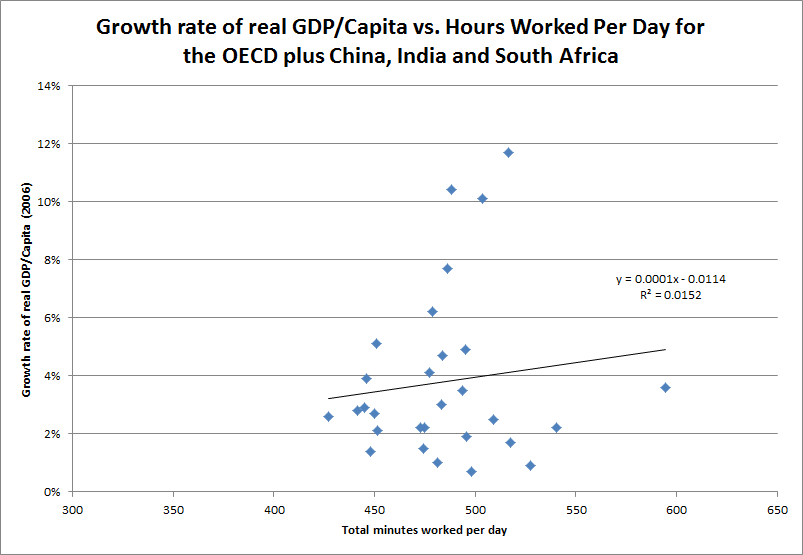

Time spent working per day doesn’t correlate significantly with growth rates in (real) GDP per capita, either (I’ve plotted it for 2006 to capture the state of the world before the financial crisis):

At least here the relationship, if you want to pretend there is one, is positive.