In my last post, I highlighted the apparent contradictions between the USA having both a “strong dollar” policy and a desire to correct their trade deficit (“re-balancing”). Tim Geithner, speaking recently in Tokyo, declared that there was no contradiction:

Geithner said U.S. efforts to boost exports aren’t in conflict with the “strong-dollar” policy. “I don’t think there’s any contradiction between the policies,” he said.

I then said:

The only way to reconcile what Geithner’s saying with the laws of mathematics is to suppose that his “strong dollar” statements are political and relate only to the nominal exchange rate and observe that trade is driven by the real exchange rate. But that then means that he’s calling for a stable nominal exchange rate combined with either deflation in the USA or inflation in other countries.

Which, together with Nouriel Roubini’s recent observation that the US holding their interest rates at zero is fueling “the mother of all carry trades” [Financial Times, RGE Monitor], provides for a delicious (but probably untrue) sort-of-conspiracy theory:

Suppose that Tim Geithner firmly believes in the need for re-balancing. He’d ideally like US exports to rise while imports stayed flat (since that would imply strong global growth and new jobs for his boss’s constituents), but he’d settle for US imports falling. Either way, he needs the US real exchange rate to fall, but he doesn’t care how. Well, not quite. His friend Ben Bernanke tells him that he doesn’t want deflation in America, but he doesn’t really care between the nominal exchange rate falling and foreign prices rising (foreign inflation).

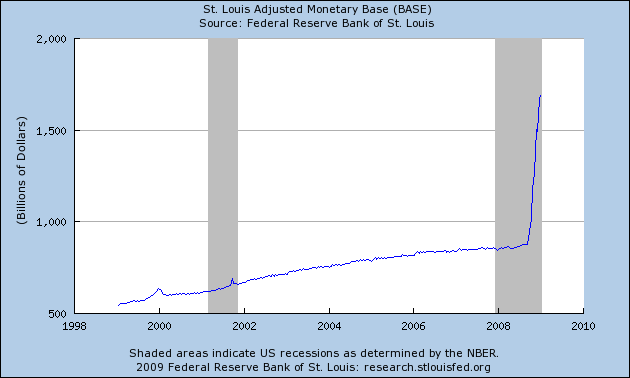

The recession-induced interest rates of (effectively) zero in America are now his friend, because he’s going to get what he wants no matter what, thanks to the carry trade. Private investors are borrowing money at 0% interest in America and then going to foreign countries to invest it at interest rates that are significantly higher than zero. If the foreign central banks did nothing, that would push the US dollar lower and their own currencies higher and Tim gets what he wants.

But the foreign central banks want a strong dollar because (a) they’re holding gazzilions of dollars worth of US treasuries and they don’t want their value to fall; and (b) they’re not fully independent of their political masters who want to want to keep exporting. So Tim regularly stands up in public and says that he supports a strong dollar. That makes him look innocent and excuses the foreign central banks for doing what they were all doing anyway: printing local money to give to the US-funded investors so as to keep their currencies down (and the US dollar up).

But that means that the money supply in foreign countries is climbing, fast, and while prices may be sticky in the short term, they will start rising soon enough. Foreign inflation will lower the US real exchange rate and Tim still gets what he wants.

The only hope for the foreign central banks is that the demand for their currencies is a short-lived temporary blip. In that case, defending their currencies won’t require the creation of too much local currency and they could probably reverse the situation fast enough afterward that they don’t get bad inflation. [This is one of the arguments in favour of central bank involvement in the exchange-rate market. Since price movements are sluggish, they can sterilise a temporary spike and gradually back out the action before local prices react too much.]

But as foreign central banks have been discovering [1], free money is free money and the carry trade won’t go away until the interest rate gap is sufficiently closed:

Nov. 13 (Bloomberg) — Brazil, South Korea and Russia are losing the battle among developing nations to reduce gains in their currencies and keep exports competitive as the demand for their financial assets, driven by the slumping dollar, is proving more than central banks can handle.

South Korea Deputy Finance Minister Shin Je Yoon said yesterday the country will leave the level of its currency to market forces after adding about $63 billion to its foreign exchange reserves this year to slow the appreciation of the won.

[…]

Brazil’s real is up 1.1 percent against the dollar this month, even after imposing a tax in October on foreign stock and bond investments and increasing foreign reserves by $9.5 billion in October in an effort to curb the currency’s appreciation. The real has risen 33 percent this year.

[…]

“I hear a lot of noise reflecting the government’s discomfort with the exchange rate, but it is hard to fight this,” said Rodrigo Azevedo, the monetary policy director of Brazil’s central bank from 2004 to 2007. “There is very little Brazil can do.”

The central banks are stuck. They can’t lower their own interest rates to zero (which would stop the carry trade) as that would stick a rocket under domestic production and cause inflation anyway. The only thing they can do is what Brazil did a little bit of: impose legal limits on capital inflows, either explicitly or by taxing foreign-owned investments. But doing that isn’t really an option, either, because they want to be able to keep attracting foreign investment after all this is over and there’s not much scarier to an investor than political uncertainty.

So they have to wait until America raises it’s own rates. But that won’t happen until America sees a turn-around in jobs and the fastest way for that to happen is for US exports to rise.

[1] Personally, I think the central bankers saw the writing on the wall the minute the Fed lowered US interest rates to (effectively) zero but their political masters were always going to take some time to cotton on.