Adam (sans-blog, but when he bothers, he writes at the South Sea Republic) pointed me to this article at The Guardian. All we need to know comes from the opening sentence:

After a break of 16 centuries, Greek pagans are worshipping the ancient gods again – despite furious opposition from the Orthodox church.

Is there a link between the rise of modern-day paganism, astrology, homoeopathic medicine etc. and the hardening of mainstream religions? If so, does one cause the other, or are they both caused by a third factor?

I wonder if it might be possible to develop some sort of measure of a country’s aggregate demand for the spiritual. You might do it by adding up all the money spent on them (including donations to religious bodies) and then adding in the value of the time spent attending religious services and festivals. I guess you could derive the latter by looking at attendance numbers, knowing something about the average duration of services and making an estimate of the value of leisure-time.

If it was feasible, you’d be able to infer answers to several questions:

The proportional break-down of the “spending” might give a truer estimate of the distribution of religious belief in society than census data … in essence, we would be looking at revealed preference rather than stated preference.

If aggregate demand for the spiritual were changing over time, that might indicate a demographic shift (from immigration, say) or — and this would be more interesting — it might provide a measure of movements in dissatisfaction with life in general. For example, a trend of decreasing demand might indicate that people are becoming more satisfied with life, or at least that they are able to find what they want in the temporal world without needing to turn to the spiritual.

*sigh* So little time, so many pointless things to waste my time thinking about.

Update 1:

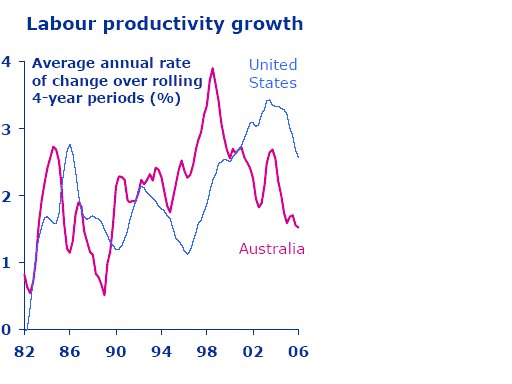

Adam read this and interpreted it as my suggesting that as people become richer, they become less religious. Rereading it, I guess that’s a fair interpretation, but it’s not what I meant at all. My current suspicion is that, on the whole, demand for the spiritual has remained remarkably constant over the years. With absolutely no figures to back it up, I reckon that aggregate demand in Australia reached a low-point in the early ’80s, increased steadily and has largely stabilised since the turn of the century. I think that the aggregate demand now is much closer to historical trend levels and that the early ’80s represented a temporary low point. I also think that the reversion-to-the-mean that we’ve seen over the last 30 years has not come from a return to 1950s-style religion, but from a general embrace of smaller aspects of spirtuality coupled with nostalgic, idealised views of the distant past and an increasing distrust of authority and “the system”. The diversity that ensued has therefore seen the rise (or perhaps more accurately, the return) of stuff like paganism and astrology, coupled with attempts to merge these small-scale, anti-establishment religious views with pop science in the form of stuff like “What the bleep do we know?” and so forth.

I’ve heard this latter stuff described as “quasi-religious” and to some extent, I agree. To the extent that they’re not codified, formalised or doctrinal, they’re only quasi-religious; but on the whole, I think that it still represents the same underlying desire for the spiritual that existed in the 1950s, simply expressed in a different form. So in that sense, there’s nothing “quasi” about it … it’s just “religious.”

Assuming that I’m correct in my gut-feel for the figures (which is why I’d love to find some proper figures instead of randomly waving my hands in the air), all of this just raises the questions of a) why is the demand there in general? and b1) why did it drop in the early ’80s? or b2) why, after dropping in the early ’80s, has it come back?