Bank of America is being handed a butt-load of cash:

Bank of America will on Friday receive $20bn in fresh capital from the US government and a guarantee on most of a further $118bn of potential losses on toxic assets.

The emergency bail-out will help to cushion the blow from a deteriorating balance sheet at Merrill Lynch, the brokerage BoA acquired earlier this month.

[…]

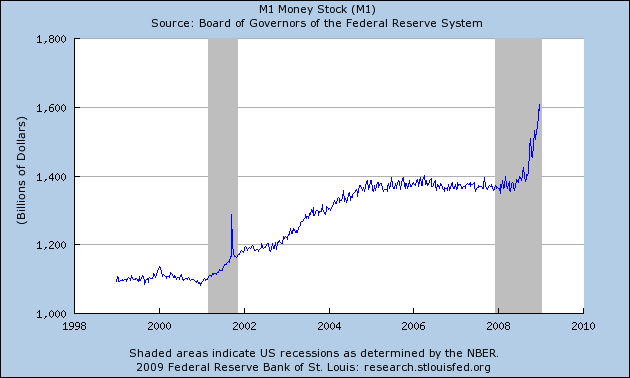

The package is on top of the $25bn BoA received from Tarp funds last October, and underscores the depth of the financial difficulties affecting the world’s leading banks.

At this point, BofA has received US$45 billion in hard cash and – more importantly, to my mind – a guarantee against US$118 billion of CDOs and related assets that they hold, many of them from their takeover of Merrill Lynch.

I don’t really want to get into whether bailouts in general are worthwhile, or if this one in particular is worthwhile. What I want to rant about is the nature of this bailout and in particular, that guarantee. It’s been done in a manner highly similar to the one given to Citigroup last year, so my criticism applies to that one as well.

Here is the joint Press Release from the US Federal Reserve, the US Treasury Department and the FDIC.

Here [pdf] is the term sheet for the deal with Bank of America.

The guarantee is against a pool of assets broken down as:

- US$37 billion worth of cash assets

- US$81 billion worth of derivatives (i.e. CDOs and other “troubled” assets)

Profits and losses for the pool will be treated as a whole. The fact that one third of the pool is cash (and cash equivalents) will have been insisted upon by the US government because they will almost surely generate at least a minor profit that will offset losses in the derivatives.

In the event of losses on the pool as a whole, BofA will take the first US$10 billion of losses; the US Government will take the next US$10 billion of losses; and any losses beyond that will be split 90/10: the US government will take 90% of them. That gives a theoretical maximum that the US government might be liable for as 10 + 90%*(118-20) = US$98.2 billion. In all likelihood, though, the cash assets will hold or increase their value, so the maximum that the US government can realistically be imagined to be liable for is 10 + 90%*(81-20) = US$64.9 billion.

But kicker is this: There was no easy way for them to arrive at that number of $81 billion. The market for cash is massively liquid (prices are available because trades are occurring), so it is easy to value the cash assets. The market for CDOs, on the other hand, is (at least for the moment and for many of them, forever) gone. Unless I’m mistaken, there are no prices available to use in valuing them. Even if there were still a market, CDOs were always traded over-the- counter, meaning that details of prices and volumes were secret.

Instead, the figure of US$81 billion is “based on valuations agreed between [BoA] and the US [Government]” (that’s from the term sheet).

I want to see details of how they valued them.

When TARP was first envisaged and it was suggested that a reverse auction might take place, the rationale was for “price discovery” to take place. The idea – which is still a good one, even if reverse auctions are a bad way to achieve it – is that since nobody knows what the CDOs are really worth, confusion and fear reign and the market drys up. Since nobody can properly value banks’ assets, nobody can tell whether those banks are solvent or not.

The generalised inability to value CDOs remains, and will continue to remain, a core issue in the financial crisis.

Suppose that the true value of BoA’s CDOs is US$51 billion. At some point, we will collectively realise that fact. The market will become (at least semi-)liquid again and the prices will, at least approximately, reflect that value. But since the BoA and US government had agreed that they were worth US$81 billion, it will technically look like a $30 billion loss and so will trigger the US government handing $19 billion (= 10 + 90%*(30-20)) to BoA and unlike the $45 billion in direct capital injection, the government will get nothing in return for that money.

Therefore, BofA had an enormous incentive to game the US government. No matter what they privately believed that their CDOs were worth, they would want to convince the Treasury that they were actually worth much more.

The US government isn’t entirely stupid, mind you. That’s why the first $10 billion in losses accrue to BoA. That means that for the money-for-nothing situation to occur, the agreed-upon valuation would need to be out by over $10 billion. On other hand, that means that instead of telling a little white lie, BoA has an incentive to tell a huge whopper of a bald-faced lie in convincing the Treasury.

That is why I want to see details on how they valued them.

Felix Salmon thinks that both Citigroup and Bank of America should be nationalised:

[N]either institution is capable of surviving in its present form much longer. [Hank Paulson and Tim Geithner] should embrace the inevitable and just nationalize the two banks.

…

[T]his isn’t a bank run: Citi and BofA aren’t suffering from liquidity problems. They have all the liquidity they need, thanks to the Fed. The problem is one of solvency: the equity markets simply don’t believe that the banks’ assets are worth more than their liabilities.

The problem being, as I explained above, that nobody knows what the assets are really worth and the market is simply assuming the worst as a precautionary measure.

I’m not yet convinced that they should be fully nationalised. I just don’t think that the government should put itself in a situation where it promises to give them money for nothing in the event that their private valuation turns out to be too high (i.e. the market is correct in believing that they’re worth bugger-all).

Barry Ritholtz wants to know why the heads of Citi and BoA are still there:

Like Citi, the B of A monies are a terrible deal for the taxpayer — not a lot of bang for the buck, and leaving the same people who created the mess in charge.

Organ transplant medicine understands certain truths: You do not give a healthy liver to a raging alcoholic, as they will only destroy the organ via their disease/bad judgment/lifestyle.

In this, I agree with him entirely.