Via Jason Kottke, I give you the true origins of breakdancing – Soviet military dancers (the glory starts around 1:00):

For comparison, the original music video for “It’s like that”:

That is all.

Research Economist at the Bank of England

Via Jason Kottke, I give you the true origins of breakdancing – Soviet military dancers (the glory starts around 1:00):

For comparison, the original music video for “It’s like that”:

That is all.

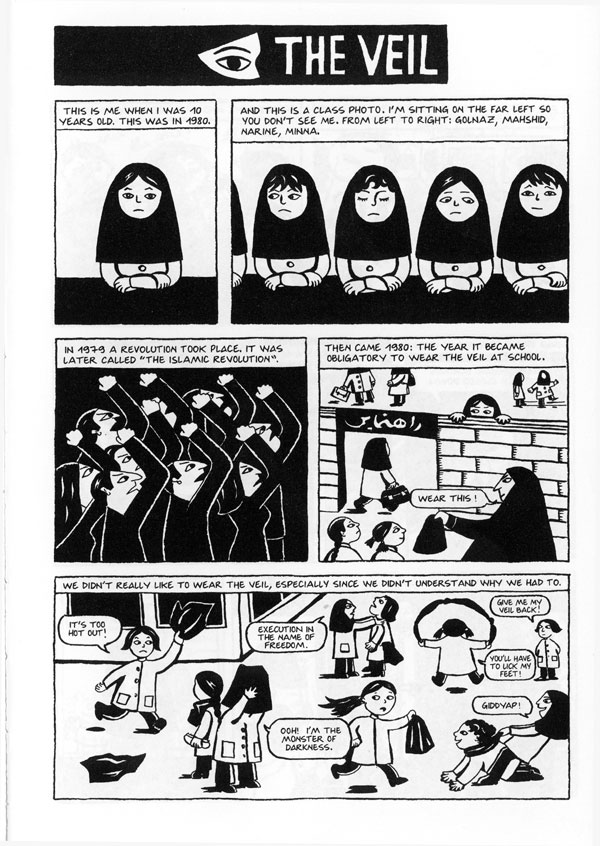

I’m reading “(The Complete) Persepolis” by Marjane Satrapi. It’s an autobiography – of her time growing up in Iran through the revolution and the war with Iraq – in the form of a graphic novel. You can see a few pages of it here. It’s wonderful. I strongly recommend it. Hoping that it doesn’t breach any copyright, here is the first page:

A friend pointed me towards this piece on the Damn Interesting site. It was so interesting that I just had to share it with my little audience. Do read the whole thing, but here are a few titbits to whet your appetite:

…

Chelyabinsk-40 was absent from all official maps, and it would be over forty years before the Soviet government would even acknowledge its existence. Nevertheless, the small city became an insidious influence in the Soviet Union, ultimately creating a corona of nuclear contamination dwarfing the devastation of the Chernobyl disaster.

…

In 1951, after about three years of operations at Chelyabinsk-40, Soviet scientists conducted a survey of the Techa River to determine whether radioactive contamination was becoming a problem. In the village of Metlino, just over four miles downriver from the plutonium plant, investigators and Geiger counters clicked nervously along the river bank. Rather than the typical “background” gamma radiation of about 0.21 Röntgens per year, the edge of the Techa River was emanating 5 Röntgens per hour.

…

The facility itself was also beginning to encounter chronic complications, particularly in the new intermediate storage system. The row of waste vats sat in a concrete canal a few kilometers outside the main complex, submerged in a constant flow of water to carry away the heat generated by radioactive decay. Soon the technicians discovered that the hot isotopes in the waste water tended to cause a bit of evaporation inside the tanks, resulting in more buoyancy than had been anticipated. This upward pressure put stress on the inlet pipes, eventually compromising the seals and allowing raw radioactive waste to seep into the canal’s coolant water. To make matters worse, several of the tanks’ heat exchangers failed, crippling their cooling capacity.

…

[T]he water inside the defective tanks gradually boiled away. A radioactive sludge of nitrates and acetates was left behind, a chemical compound roughly equivalent to TNT. Unable to shed much heat, the concentrated radioactive slurry continued to increase in temperature within the defective 80,000 gallon containers. On 29 September 1957, one tank reached an estimated 660 degrees Fahrenheit. At 4:20pm local time, the explosive salt deposits in the bottom of the vat detonated. The blast ignited the contents of the other dried-out tanks, producing a combined explosive force equivalent to about 85 tons of TNT. The thick concrete lid which covered the cooling trench was hurled eighty feet away, and seventy tons of highly radioactive fission products were ejected into the open atmosphere.

Incredible.

From the pub last night:

“Swishy pants” to an American means “tracksuit bottoms” and to a Briton (a home-county Englishman, to be particular) it means “fancy underwear.”

Dreams are more negative than real life: Implications for the function of dreaming

ki; Antti Revonsuo

ki; Antti RevonsuoMy sister (in law) wondered why the government, if you can call it that, of Burma (Myanmar) isn’t letting foreign aid into the country after Cyclone Narqis (that’s a hurricane to any North Americans in the audience) ripped through the country earlier this month. My quick-and-dirty response:

Update:

And of course …

Believing in something and being willing to act on it are two different things. It is terribly difficult to confront authority. Confrontation itself is hard. It’s awkward; uncomfortable. Your face may flush, you might sweat, or stammer. Worse, you can find your mind slipping. Your memory may fail you, the speed or rigour of your thought may lessen and the strength of your argument weaken as a result.

When the confrontation is with authority the difficulty is even worse. Many people have an instinctive acquiescence towards figures of power or authority. It can feel wrong in the gut to openly disagree with them. If you fear that the confrontation may result in bridges being burned, or if you feel that you owe the figure of authority in some way, it can be impossible.

Understand that I am not referring to the discussion of something that you feel ought to change with people you consider your peers. That is easy and even serves as a sort of release-valve for tension on the topic by letting you know that you’re not alone in your beliefs. A simple suggestion to a figure of seniority can often be comfortably managed by most. I am speaking of a push for change; seeking actively to change the actions, if not the very mindset, of an authority figure who may be reticent to the idea.

This is one of the reasons, if not the ultimate justification, for anonymous ballots. The safety of anonymity can free people of their inhibitions and allow them to speak as they truly feel. But what of organisations that do not have a democratic structure? What of the hierarchical power structures of firms and government agencies, of schools and universities and charities?

Hierarchies allow for genuine decision making over the endless, cacophonic debates of pure democracy, but they come at the cost of hampering information flow (at an extreme, it becomes unidirectional) and making people at the bottom feel ineffective or inconsequential.

As a society, we seem to have settled on the idea of power being locally hierarchical, but globally competitive between those separate hierarchies. This concept works best when those hierarchies compete not just in the ideas that they represent, but also for the individuals that they are made up from. The competition for individuals should mean that there is a countervailing force to the negative aspects of hierarchies: in order to attract and keep the best people, the hierarchy must work to involve those people in its thinking.

I am fine with this concept – I do not support radical decentralisation – but we need to recognise that people are not free to costlessly move between hierarchies. This means that the incentive to involve them in the hierarchies’ thinking processes is lessened. It seems reasonable to assume that as the cost of moving to another hierarchy as a fraction of individual benefit gained goes down, the more involved a person will be invited to be. In equilibrium, we would therefore expect the degree of involvement to decrease monotonically as you move down any given hierarchy.

While I do not wish for a pure democracy in everything, I think that the optimum would involve deliberate mechanisms for allowing ideas and information to pass upwards through a hierarchy. Perhaps an open market for ideas on each level, with those “voted best” being passed up to the level above?

This puzzle-game is brilliant. Spare an hour for it.

In another great example of bouncing topics around in the often-academic blogs, we have this:

Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers wrote an article for Cato Unbound: “Marriage and the Market“. Here is a brief summary of their idea (the exact snippet chosen is stolen directly from Arnold Kling):

So what drives modern marriage? We believe that the answer lies in a shift from the family as a forum for shared production, to shared consumption…the key today is consumption complementarities – activities that are not only enjoyable, but are more enjoyable when shared with a spouse. We call this new model of sharing our lives “hedonic marriage”.

…Hedonic marriage is different from productive marriage. In a world of specialization, the old adage was that “opposites attract,” and it made sense for husband and wife to have different interests in different spheres of life. Today, it is more important that we share similar values, enjoy similar activities, and find each other intellectually stimulating. Hedonic marriage leads people to be more likely to marry someone of their similar age, educational background, and even occupation. As likes are increasingly marrying likes, it isn’t surprising that we see increasing political pressure to expand marriage to same-sex couples.

…the high divorce rates among those marrying in the 1970s reflected a transition, as many married the right partner for the old specialization model of marriage, only to find that pairing hopelessly inadequate in the modern hedonic marriage.

It produced a flurry of responses and reactions, but the chain I want to follow is this one:

Which finally brings me to why I wrote this entry. I love this sentence from Tyler:

Symbolic goods usually have marginal values higher than their marginal costs of production; Americans for instance love the idea of their flags but the cloth is pretty cheap, especially if it comes from China.

Brilliant. 🙂

Scott Adams has a thing where he considers humans (well, all animals, I guess) to be “moist robots,” in that we have no free will. I tend not to think about it too much, but here are some recent bits of research that strike me as interesting: