I’ve been meaning to read this piece by Martin Wolf (chief economics commentator for the Financial Times) for the last week. As it happens, it’s a “me too” response and a minor expansion to this brilliant piece by Raghuram Rajan (professor of finance at the Graduate School of Business at the University of Chicago and former chief economist at the IMF). I recommend reading both of them in full. Here are some cut-down snippets from Rajan’s efforts:

The typical manager of financial assets generates returns based on the systematic risk he takes – the so-called beta risk – and the value his abilities contribute to the investment process – his so-called alpha.

…

[T]here are only a few sources of alpha for investment managers. One of them comes from having truly special abilities in identifying undervalued financial assets. [e.g. Warren Buffet]

…

A second source of alpha is from … using financial resources to create, or obtain control over, real assets and to use that control to change the payout obtained on the financial investment. [e.g. a venture capitalist]

…

A third source of alpha is financial entrepreneurship or engineering – creating securities or cash flow streams that appeal to particular investors or tastes. As long as the investment manager does not create securities that exploit investor weaknesses or ignorance (and there is unfortunately too much of that), this sort of alpha is also beneficial, but it requires constant innovation.

…

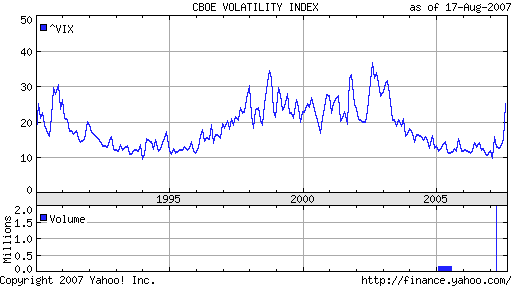

How do untalented investment managers justify their pay? Unfortunately, all too often it is by creating fake alpha – appearing to create excess returns but in fact taking on hidden tail risks, which produce a steady positive return most of the time as compensation for a rare, very negative, return.

…

True alpha can be measured only in the long run and with the benefit of hindsight – in the same way as the acumen of someone writing earthquake insurance can be measured only over a period long enough for earthquakes to have occurred. Compensation structures that reward managers annually for profits, but do not claw these rewards back when losses materialise, encourage the creation of fake alpha. Significant portions of compensation should be held in escrow to be paid only long after the activities that generated that compensation occur.

Martin Wolf’s addition comes in like this:

By paying huge bonuses on the basis of short-term performance in a system in which negative bonuses are impossible, banks create gigantic incentives to disguise risk-taking as value-creation.

We would be better off with Jupiter’s 12-year “year”, since it takes about that long to know how profitable strategies have been. The point is that a year is an astronomical, not an economic, phenomenon (as it once was, when harvests were decisive). So we must ensure that a substantial part of pay is better aligned to the realities of the business: that is, is made in restricted stock redeemable over a run of years (ideally, as many as 10).

Yet individual institutions cannot change their systems of remuneration on their own, without losing talented staff to the competition. So regulators may have to step in. The idea of such official intervention is horrible, but the alternative of endlessly repeated crises is even worse.

Dani Rodrik has been noting for a while that Martin Wolf seems to be coming ’round to his point of view in economic development. I’ve seen the same thing and it’s great to see.