It’s old news by now, but in case anybody missed it, the excellent Bryan Palmer has resumed blogging at ozpolitics. This is a Good Thing ™.

Needing a visa to visit America

Australia, like most of Western Europe and a few other countries, is on America’s “visa waiver” programme, which lets people travel to the USA for up to 90 days at a time without first applying for a visa, although the US can still deny entry to anybody that doesn’t answer the immigration official’s questions to their satisfaction.

By comparison, Australia requires that all visitors from everywhere except New Zealand have a visa. It’s a staggeringly simple and not overly expensive process that can happen online, but it’s a visa-requirement nonetheless.

It looks like the US is moving to an Australian-style system. They’re still calling it a “visa waiver,” but the requirement that I register before entering the US and that they reserve the right to deny my registration seems a lot like a visa to me. From the article:

Passengers travelling to the United States from countries whose citizens do not need visas must register online with the US government at least 72 hours before departure [from January 2009]

…

Although the new rule requires 72 hours advance registration, it will be valid for multiple entries over a two-year period. The rule will only apply to citizens of the 27 visa waiver programme countries

…

A Homeland Security official said the new measure would require the same information that passengers now have to include on the I-94 immigration form they must fill out before entering the US. He said Australia has been using a similar system for several years.

Presumably this means that the US will be more likely to start adding the newer members of the EU to the “visa waiver” programme.

Oh please, oh please, oh please

Mr. Rudd, call Andrew Leigh. Call him now. Speaking on Indigenous policy, he writes:

- School attendance rates are appalling, and as Woody Allen says “90% of life is just showing up”. So pay Indigenous children to attend school.

- Literacy and numeracy gaps are large, and part of the difference may be teacher quality. So the federal government should promise bonuses of up to $50,000 to teachers who can get large improvements in performance in Indigenous schools. Teaching disadvantaged kids is the most important job in Australia – so why does no-one doing it earn a six-figure salary?

- Indigenous people are overrepresented in Australia’s jails, which do little more than warehousing. Since many are now private, why not rewrite the contracts, making payment conditional on post-release recidivism and earnings? Let’s create incentives for those who run jails to do more education, and less clock-watching.

- A major impediment to children attending school is drunkenness in communities. But a ban is a drastic measure. Let’s allow communities to set their own tax rates on alcohol, and keep the revenue (remember, a ban is effectively a tax rate equivalent to the cost of petrol to the nearest no-ban town).

- As many Indigenous policies as possible (including those above) should be subjected to rigorous randomised trials. Those that fail should be discarded without sentiment, and those that succeed should be expanded. We know from the headline indicators that many Indigenous policies haven’t worked; it’s time to start sorting out the wheat from the chaff.

Amen.

Tyranny and the ethical removal of children

I promise this’ll be my last post on the whole apology business for a while. 🙂 In response to my entry, “An apology for what?“, Cam Riley posted this comment:

Tyranny is tyranny – and removing children from their parents due to their skin colour is a tyrannous act. The goal of republican government is to remove all tyranny from the system. Consequently, past tyrannous acts need to be recognized as such.

I responded pretty quickly with:

I’m not denying that it was an act of tyranny (in the sense of oppression, not in the sense of a single ruler), only that the word “tyranny” is one with massive emotional and judgemental baggage in the same way as “genocide”. Its use may be justified in a literal sense, but it will rarely serve to improve the situation in a world of real politik. In any event, I accept the pragmatic necessity of an apology even if I do not fully accept the moral obligation to apologise today for something that was honestly believed to be just at the time.

I was thinking about this over dinner and it seems to me that there are three largely distinct issues at point here:

- The disenfranchisement of a people, meaning that any act of government concerning them was an act of tyranny

- The ethical question of when it is acceptable to remove a child from its family

- The question of whether the policy of forced removal “worked” in the sense of improving the livelihoods of those children

As I previously mentioned, I do not deny that the stolen generations represented an act of tyranny. That is a definitional consequence of Aboriginal disenfranchisement. But a tyrant may make a good decision that benefits people, just as a democracy may make a bad decision that harms them. There is no disputing the injustice of Aboriginal disenfranchisement in and of itself, but it was parallel to and, at worst, an enabler of the tragedy of the stolen generations, not the cause of it and therefore not the source of the moral wrong.

On the second point, society today still accepts that it is sometimes warranted to forcibly remove a child from its family. This is a terribly difficult decision, but as a society, we judge that it is ethical when that child is held to be in considerable danger. In the UK, for example,

A court can only make a care order if it is sure that:

- the child is suffering, or is likely to suffer, significant harm

- the harm is caused by the child’s parents

- the harm would be caused because of insufficient care being given to the child by the parents in the future

- the child is likely to suffer harm because they are beyond parental control

I accept as fact that the Australian government’s policy of removal was based, for the most part, on the ethnicity of the children taken and not their individual safety. That on its own was immoral and warrants reparation to balance the damage done. The problem is that, while the act was wrong, it was performed under the honest (but false) belief that it was the best thing to do. At the time, I have no doubt, it would have been widely believed that although the removal of children was regrettable, the ends justified the means.

Which brings us to the third point. I seriously wonder whether the stolen generation would be as much of an issue today if the policy had been a roaring success. What if the democracy, acting tyrannically over the disenfranchised, made a bad decision that nevertheless turned out to be beneficial to all involved, with Aboriginals today enjoying educational, health and income outcomes equal to non-indigenous Australians? It ought to still be as much of an issue, but I suspect that it wouldn’t be.

The difficulty in passing judgement on the drafters of the Aboriginal Protection Act (1869) is that while we have the benefit of perfect hindsight, they did not enjoy the benefit of perfect foresight. Does anyone seriously claim that they still would have gone ahead with it if they had they known – and comprehended – what the full consequences of their actions would be?

All of which means that I find myself (a) supporting calls for reparation and (b) opposing the apology on moral grounds, but supporting the necessity of it on pragmatic grounds.

On the necessity of an apology

Earlier this morning I asked:

Should we hold the actions of the past against the moral standard of today, especially if those actions were held to be just at the time?

I asked because it’s not at all clear to me that we ought to. In response by email, a good friend of mine argued that whatever the answer to my question, it simply isn’t relevant to the practicality of moving forward, because both the perpetrator (the government, not the necessarily the individuals that operated it at the time) and the victims are still around to face each other.

To quote the SMH in quoting Susan Butler, editor of the Macquarie Dictionary:

It is “something that every child knows”, says Susan Butler, editor of the Macquarie Dictionary and Australia’s unofficial keeper of the national vernacular.

“When you say you are sorry, life can go on. Your brother, sister, friend will drop the dispute, whatever it was, and enter into normal relations again. To withhold that ‘sorry’ utterance is to continue the war.”

Like “Good morning” and “How are you?”, she says, it is what linguists call a phatic expression; its meaning lies in its utterance, not necessarily in the content of its words.

In other words, when you have wronged someone, and refuse to say sorry, you are responsible for perpetuating the dispute. You all know that – how many times has each of you fumed over the absence of an apology rather than the original act?

…

The apology is about choosing not to act like dicks, something on which we’ve failed spectacularly so far.

It’s a really strong argument and I take his point. He missed a bit further down in the article, though:

A document handed by the Stolen Generations Alliance to Macklin last week, on behalf of victims and their families, said they overwhelmingly desired money to make the reparations process meaningful.

And Butler realises this, too. The nature of the gesture – its wording and what comes after – remains important.

Examining the seemingly simple five-letter word in a recent edition of the Walkley Magazine, she ended by saying that not saying sorry is as damaging as an insincere sorry.

“Phatic expressions may be about emotion rather than meaning but that is not to say they are not complex and powerful utterances. How you say, or don’t say, ‘Good Morning’ can encapsulate your attitude to life and reveal the state of your personal account in the bank of social capital.”

An insincere apology, given grudgingly and against the wishes of the person saying it, rarely achieves much and sometimes only serves to poison the future relationship. If the apology is needed to move forward, as my friend powerfully argues, it needs to be a real one. It can be embarrassed and awkward, but it needs conviction.

It also needs to be accepted. The government will easily be able to drum up a few indigenous Australians to forgive them on national television, but unless the vast majority of Australian Aboriginals do the same – and I’m not sure they will unless it comes with financial reparations – it won’t solve a thing.

Update: Post #3 in this mini-series: “Tyranny and the ethical removal of children“

An apology for what?

For any non-Australians in the audience, the new Australian government is doing what the previous lot refused to do: apologise on behalf of the parliament and government of Australia to the indigenous people of Australia for the forced removal of children from their families for approximately 100 years until 1969.

I want (as should be little surprise to anyone who knows me) to abstract away from the specifics of this a little. When is an apology for some past injustice warranted?

Should we hold the actions of the past against the moral standard of today, especially if those actions were held to be just at the time? If the answer is ‘yes’, how far back in history is it acceptable to apply our outrage? We don’t judge the Romans for having sex with children or the Aztecs for their human sacrifices – we simply view them as having taken place in an environment of ignorance.

The Aztecs were not only a long time ago, but also from a different cultural heritage to us. The Romans were a long time ago and also our cultural ancestors, so we can’t simply say that we only judge our own.

So where (and why) do we draw a line in the sand?

If someone can explain that to me, then I can happily endorse the apology (I already accept it). People who argue that since we didn’t do it (after all – we weren’t around then) we shouldn’t apologise are missing an important point: The government and the parliament of Australia were around then and did play an active role. The difference between the (wo)man and the office is important here. The office of the government of Australia did the Bad Thing. If it is right to judge the past against the moral measures of the present, then it is also right for the office of the government of Australia to apologise. The particulars of who is occupying that office now is of little consequence.

The only way out, from my point of view, is if there were a significant change of constitution in the intervening period, so that it might be legitimately said that the government of today is not in any way the government that existed at the time. Is that why we let the Romans off the hook? We would judge them, only they don’t exist any more?

Back to the particulars: I don’t really mind whether we call it tyranny (although I think that choice of words is inflammatory) or whether Labor supporters want to poke fun at the Coalition (although I think that at least some of the Coalition’s concerns are legitimate). I think that the apology is a symbolic gesture that, on its own, will help not at all. I think that the Aboriginals of Australia have complaints (most but not all of them legitimate) far deeper and wider than the stolen generations and that the stolen generation issue simply became an emblematic focal point.

The apology is no skin off my nose and if it makes people feel better for a while, go nuts. But don’t try telling me that it’ll do a damned thing to improve the lives of Aboriginals in Oz. For that we need real policies of support from the government and real acknowledgement of the realities of the world from the Aboriginal community.

Update: I got an excellent response from a good friend of mine.

Sweating the small stuff

Idle curiosity

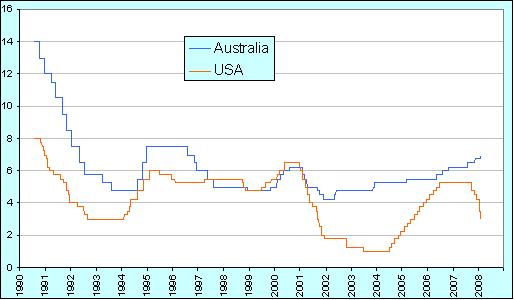

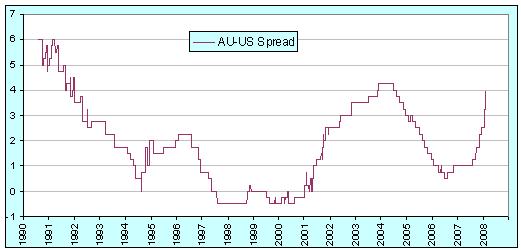

In case anyone is interested, here are graphs of Australia’s and America’s base (cash) target rates and the spread between them.

Source: RBA, Federal Reserve

Heading for parity?

Canadians celebrated when the Canadian dollar (“the loonie”) hit parity with the U.S. dollar in September last year. At the time, there was some speculation about whether the Australian dollar might follow suit. You’re going to see some more speculation over the next few days. Fundamentals aside, there are two main things that are serving to push the Australian dollar up: the resource boom in Australia and the spread in the interest rates between the two countries, and the latter of those is about to jump.

The US Federal Reserve cut interest rates by 75 basis points a week ago in a surprise, out-of-cycle move. Today they are expected to announce a further cut. Apparently the markets are predicting that there’s an 80% likelihood that it will be a further 50 basis point drop. Next week on the 5th of February, on the back of some truly disastrous inflation figures, the Reserve Bank of Australia will probably raise their rate by 25 basis points. That would be an enormous, 150-point increase in the spread in the space of just two weeks. On that basis, it’s not at all surprising that the markets are already pushing up the AUD.

Australia, you’re not as rich as you think you are

We’re covering this in my EC102 classes this week and I thought it interesting enough to share with a wider audience:

Looking at what goes into GDP is usually a pretty tedious affair, but the simplest way to think of it is like this: GDP is meant to represent the total value added. It is new work done; new stuff produced.

One upshot of this is that new houses are counted in GDP, while sales of existing houses are not. This is because sales of existing houses are just value transferred – an exchange of assets – and so don’t represent new effort. That’s not quite true. The real-estate agent fees and legal fees associated with the sale count, since they are new work done: they add new value by facilitating the trade.

Here’s a trick in looking at value added: we only need to look at the prices of final goods. This is because the price of the final good will represent the total value added along the entire production chain. The typical example of this used in introductory textbooks is bread:

| Who | Sells | Price | Value added |

| Farmer | Wheat | $0.10 | $0.10 |

| Miller | Flour | $0.20 | $0.10 |

| Baker | Bread | $0.45 | $0.15 |

| Supermarket | Packaged and convenient bread | $1.00 | $0.55 |

The price of the final good – packaged, convenient bread – is $1.00, which exactly equal to the sum of all the value added. So when the statisticians want to calculate a country’s GDP, they can ignore all the intermediate levels and just add up all the final goods that were produced.So what counts as a final good? Anything that gets sold to someone for consumption or investment. That might be to an individual, or to a private firm, or the government, or someone overseas. (Of course, since I buy both bread and flour from my supermarket, flour is sometimes an intermediate good and sometimes a final good; but it’s easy to tell which is which – flour sold by the supermarket is final, while flour sold by the miller is intermediate.)

Now consider a country that has a large natural resource sector. Australia is a great example. So are all the oil exporting countries. We’ll pick the mining of iron ore in Australia as an example. Just like with the wheat above, there is a whole range of production possibilities based on the iron ore. However, when it’s exported, the final good that gets counted from the point of view of the Australian economy is the iron ore in the ship as it sails off to another country.The mining companies are definitely adding value. They’ve got to find the stuff in the first place, dig it up, clean it a bit to get rid of the dirt, transport it to the coast and then ship it overseas. They’ve also got to maintain all their equipment and allow for the fact that they wear out over time. All of that is new effort. But the price that India or China pays for the ore is more than cost of doing all of that. A large fraction of the price they pay represents the market value of the underlying asset – the ore – itself. But since the mining company didn’t actually produce the ore, that part of the price shouldn’t really count in GDP, for the same reason that when existing houses are sold, only the agent and legal fees are counted. None of this is really news.

When natural-resource-based industries are only a small part of a country’s economy, there’s not too much distortion, so we tend not to worry about it. But when those industries represent a large share of the national income, then the overestimates can be significant. In Australia, mining represents about 6.7% of the national economy. A fair chunk of that will be “true” value added, but a large share of it is really just the transfer of assets. How much? Well, BHP currently has a Return on Equity of 49%, while the long-run, risk-free return on capital is more like 8-10%. So as a very rough guess, assuming that BHP is representative of the mining industry as a whole and that the mining industry is competitive, we might suggest that Australia’s “true” GDP is at least 39% * 6.7% = 2.6% smaller than we think it is.

Some people might at this point wonder about the farmer back in the bread example. What if the farmer who, like BHP, is taking something from the land, is actually only adding 60% of the value that we think she is? The answer lies in the fact that there is a large production chain that builds up from the farmer’s wheat. Even if we remove a large fraction of the farmer’s value-added, that is only a small share of the total value added that we see in the final good’s price. So we would expect this overestimate to be very small overall. The point about mining is that we are only adding a small amount of value relative to that of the asset we are trading away, so as a percentage of the final good, the asset itself is quite large.