Andrew Norton doesn’t think much of this article by Christine Wallace in the Griffith Review, in which she argues that the Coalition under Howard has instigated libertarian policies by stealth. He calls it “a dozen or so pages of ignorance and silliness,” citing this paragraph from page 8 in particular:

The libertarian logic is that, since personal freedom and the existence of free markets are inextricably entwined, and since – as Bork puts it – “vigorous” economies are vulnerable to being “enfeebled” by particular cultural practices, then the champions of personal freedom have a licence to police cultural practices – in the interests of freedom and economic vigour. Thus libertarians can reason that difference (for example, multiculturalism, homosexuality) must be eliminated so that the economy can function better – reasoning that is absurd, to say the least.

A commenter on Andrew’s blog also highlighted this bit on the previous page:

The central difference between the Howard Government and the Hawke/Keating Governments is that the Labor governments saw a crucial role for the public sector … especially in relation to issues of economic inequality; about which libertarians are unconcerned.

First a confession: I’ve not read more than two or three pages of Christine’s article. Still, if the blogosphere isn’t a place for partially informed comment, I don’t know what is. In the interests of fairness, though, I will disagree (slightly) once with Andrew and once with Christine …

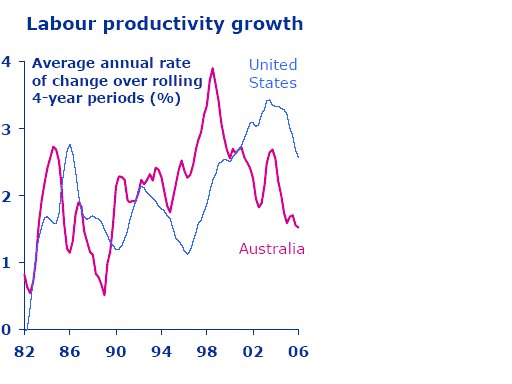

In the paragraph that drew Andrew’s ire, Christine argues that the libertarian pursuit of free markets justifies cultural homogeneity. Andrew’s implicit criticism certainly seems to make sense: why should free markets and cultural heterogeneity be mutually exclusive? But it is worth noting that Christine may – at least to some extent – have an unpleasant point. For a market to operate efficiently requires trust between its participants. A market can certainly operate without trust if institutions are sufficiently advanced and corruption-free, but the enforcement costs they impose are a classic form of market failure, along with moral hazard and adverse selection. Even with good institutions, market efficiency is optimised by increasing trust. However, as Andrew Leigh has observed for Australia [here and here] and Robert Putnam has found for the USA [here], ethno-linguistic diversity breeds mistrust. In so far as they proxy for culture, Chrstine’s point at least partially stands.

Now back to Christine. She reckons that libertarians are unconcerned about inequality. It’s obviously a generalisation, but even in general, it’s misleading. While I’m sure that libertarians are not concerned about inequality per se, I’m equally sure that they are concerned with unwarranted inequality. Classic theory of the firm suggests that in perfectly competitive markets, a person’s wage will equal the value of their marginal product. Presuming (safely enough) that different occupations have different marginal products (so an engineer will contribute more to a firm’s profits than a cleaner), if people at the top of the pile are being paid more than their marginal product and people at the bottom are being paid less than theirs, a libertarian would oppose the excess inequality that resulted.