… being both British and Australian. It only took seven and a half years of living in Ol’ Blighty to do it. The ceremony took place in the chambers of the Camden Council Hall — all dark timber and green leather. There were about 30 of us in the ceremony. Roughly half chose to swear their allegence by God, and half to affirm it without any religious reference. Now I get to wait six weeks before getting my British passport.

… being both British and Australian. It only took seven and a half years of living in Ol’ Blighty to do it. The ceremony took place in the chambers of the Camden Council Hall — all dark timber and green leather. There were about 30 of us in the ceremony. Roughly half chose to swear their allegence by God, and half to affirm it without any religious reference. Now I get to wait six weeks before getting my British passport.

Double-yolk eggs, clustering and the financial crisis

I happened to be listening when Radio 4’s “Today Show” had a little debate about the probability of getting a pack of six double-yolk eggs. Tim Harford, who they called to help them sort it out, relates the story here.

So there are two thinking styles here. One is to solve the probability problem as posed. The other is to apply some common sense to figure out whether the probability problem makes any sense. We need both. Common sense can be misleading, but so can precise-sounding misspecifications of real world problems.

There are lessons here for the credit crunch. When the quants calculate that Goldman Sachs had seen 25 standard deviation events, several days in a row, we must conclude not that Goldman Sachs was unlucky, but that the models weren’t accurate depictions of reality.

One listener later solved the two-yolk problem. Apparently workers in egg-packing plants sort out twin-yolk eggs for themselves. If there are too many, they pack the leftovers into cartons. In other words, twin-yolk eggs cluster together. No wonder so many Today listeners have experienced bountiful cartons.

Mortgage backed securities experienced clustered losses in much the same unexpected way. If only more bankers had pondered the fable of the eggs.

The link Tim gives in the middle of my quote is to this piece, also by Tim, at the FT. Here’s the bit that Tim is referring to (emphasis at the end is mine):

What really screws up a forecast is a “structural break”, which means that some underlying parameter has changed in a way that wasn’t anticipated in the forecaster’s model.

These breaks happen with alarming frequency, but the real problem is that conventional forecasting approaches do not recognise them even after they have happened. [Snip some examples]

In all these cases, the forecasts were wrong because they had an inbuilt view of the “equilibrium” … In each case, the equilibrium changed to something new, and in each case, the forecasters wrongly predicted a return to business as usual, again and again. The lesson is that a forecasting technique that cannot deal with structural breaks is a forecasting technique that can misfire almost indefinitely.

Hendry’s ultimate goal is to forecast structural breaks. That is almost impossible: it requires a parallel model (or models) of external forces – anything from a technological breakthrough to a legislative change to a war.

Some of these structural breaks will never be predictable, although Hendry believes forecasters can and should do more to try to anticipate them.

But even if structural breaks cannot be predicted, that is no excuse for nihilism. Hendry’s methodology has already produced something worth having: the ability to spot structural breaks as they are happening. Even if Hendry cannot predict when the world will change, his computer-automated techniques can quickly spot the change after the fact.

That might sound pointless.

In fact, given that traditional economic forecasts miss structural breaks all the time, it is both difficult to achieve and useful.

Talking to Hendry, I was reminded of one of the most famous laments to be heard when the credit crisis broke in the summer. “We were seeing things that were 25-standard deviation moves, several days in a row,” said Goldman Sachs’ chief financial officer. One day should have been enough to realise that the world had changed.

That’s pretty hard-core. Imagine if under your maintained hypothesis, what just happened was a 25-standard deviation event. That’s a “holy fuck” moment. David Viniar, the GS CFO, then suggests that they occurred for several days in a row. A variety of people (for example, Brad DeLong, Felix Salmon and Chris Dillow) have pointed out that a 25-standard deviation event is so staggeringly unlikely that the universe isn’t old enough for us to seriously believe that one has ever occurred. It is therefore absurd to propose that even a single such event occurred. The idea that several of them happened in the space of a few days is beyond imagining.

Which is why Tim Harford pointed out that even after the first day where, according to their models, it appeared as though a 25-standard deviation event had just occurred, it should have been obvious to anyone with the slightest understanding of probability and statistics that they were staring at a structural break.

In particular, as we now know, asset returns have thicker tails than previously thought and, possibly more importantly, the correlation of asset returns varies with the magnitude of that return. For exceptionally bad outcomes, asset returns are significantly correlated.

Note to self: holidaying in Greece will soon be cheap

Megan McArdle directs the world to this piece in the FT. From the FT article:

The European Commission said on Tuesday it would endorse Athens’ plan to bring back under control the public sector deficit, which last year reached almost 13 per cent of gross domestic product.

…

Under a three-year plan, the Greek government seeks to cut the national budget deficit to less than 3 per cent of GDP by the end of 2012.

and:

In response to criticism that earlier plans had not included sufficient spending cuts, Mr Papandreou also announced an across-the-board freeze in public sector wages which, together with cuts in allowances, would reduce the public sector wage bill by 4 per cent. The government has also pledged to raise the retirement age.

If the Greek government can achieve this without massive, nation-wide strikes, I’ll be terrifically impressed. Megan’s comments:

Everyone is expressing optimism. But while this sort of belt-tightening is necessary for Greece to stay in the EU, it’s going to come at a huge cost. Greece is already in recession–that’s why its budget problems loom so large–and the fiscal contraction will only make them deeper. Meanwhile, the EU will be setting its interest rates to meet the needs of larger, healthier members (and inflation-hawk bondholders). Tight fiscal and monetary policy means a long, painful period ahead for the Greeks.

This is the dilemma that faced Argentina with its monetary peg to the dollar; ultimately, it led to devaluation and default. We will see if Greece can whether [sic] it better.

I don’t think that this sort of belt-tightening is strictly necessary in the near term. Germany will, again, fund a bail-out if it really comes down to it because, if nothing else, the loss to Germany of a member of the EU dropping the currency is greater than the loss to Germany of paying for Greece’s debt.

It’s clearly necessary in the long term that Greece get it’s fiscal house in order, but since they’re in such a severe recession, this isn’t really the time to do it (financial market pressure aside). This is, in essence, the same debate that is gripping America, although there the pressure to address the deficit is coming from a successful political strategy of the opposition rather than, much as that same opposition might like, pressure from the markets.

Ultimately, what the EU needs is individual states to be long-term fiscally stable and to have pan-Europe automatic stabilisers so that areas with low unemployment essentially subsidise those with high unemployment. Ideally it would avoid straight inter-government transfers and instead take the form of either encouraging businesses to locate themselves in the areas with high unemployment, or encouraging individuals to move to areas of low unemployment. The latter is difficult in Europe with it’s multitude of languages, but not impossible.

In a perfect world where all regions of the EU currency zone were equally developed, this would simply replace the EU development grants. But this isn’t a perfectly world …

Party discipline in the Republican Party

Inspired by this post by Cam Riley … Any observer of U.S. politics could not have failed to notice the incredible level of party discipline that the Republicans, particularly in the Senate, have achieved over the last year or six. This may be something new to Americans, but it’s rather common to Britons and Australians, who generally get more excited when somebody — anybody! — breaks the party line. The party discipline of the Australian Labor Party, in particular, is phenomenal.

I understand that the generally accepted explanation for the differences between the USA and Australia in this regard focuses on the sources of funding for campaigns. In Australia, all campaign funds come from the party — individual candidates cannot raise money directly — where as in the US, there’s a combination of party-supplied and individually-raised funding.

That then suggests two possible reasons for the new-found Republican discipline:

- Republican congressional candidates have started to take a larger fraction of their total campaign funding from the party itself; and/or

- Advocacy groups that support policies we stereotypically associate with the Democratic Party have not been giving any money to Republicans.

If it is the second reason, then that is a tactical error, and a foolish one, on the part of those advocacy groups.

The dude at Macquarie …

The Reserve Bank of Australia just decided, somewhat unexpectedly, to keep interest rates on hold. Channel 7 news needed to spin it into a story, though, so they did the usual thing of getting a talking head from the mythical (in Australia, at least) Macquarie Bank to say something. Unfortunately, there was a guy in the background who chose that moment to look at topless pictures of Miranda Kerr. Here’s the clip. The guy starts looking at them at the 1:00 mark.

I don’t think he’ll be fired.

It looks like he was opening images from an email and that gives him a little cover. If the sender was a Macquarie employee then they will have some serious problems, it being considered worse to send “offensive” material than to receive it.

The dude will probably get an official reprimand and he might not get the same pay rise as others in his team next time ’round (at the least, he was just demonstrably slacking off from work), but I think that’ll be about it for him.

I think that Macquarie will look at their email and web-browsing policy again and consider increasing the paranoid parameter of their filters. There are plenty of algorithms for detecting skin tones in images and I’m 99% sure that they’ve been incorporated into email filters. It’s just a question of turning them on.

I think they’ll also reconsider their policy on having their talking heads stand in front of an office like that. I know they do it to look more important — I’ve taken 3 minutes out from my dazzlingly busy schedule to explain that your mortgage payments won’t change today, but will probably go up in a month or two. Gosh, don’t I look impressive? — but exactly this sort of stuff is the risk with which it comes. I’ve seen other stupid things going on behind US presenters, so I don’t think they’ll stop the practice, but they might consider staging the background a little more than just sticking a big cardboard Macquarie sign in there.

In the end, it just shows what everybody working in an open-plan office already knows: the exact position and alignment of your desk is of crucial value.

Today’s must read: Russian economic development, as seen through McDonalds

Go here, at the NY Times, and read the article now. I’ll give a few tiny snippets to whet your appetite, but you really do need to read the whole thing:

Today, private businesses in Russia supply 80 percent of the ingredients in a McDonald’s, a reversal from the ratio when it opened in 1990 and 80 percent of ingredients were imported.

[…]

From the day it opened the gates on the $50 million factory, McDonald’s had intended to hand out its functions to other businesses and eventually shut it down, said Khamzat Khasbulatov, the director of McDonald’s in Russia.Arms-length transactions for supplies allow McDonald’s to step back from the interaction of franchisees and food-processing companies, sparing them a headache. Russia’s 235 restaurants have not yet been franchised.

“We knew from Day 1 that our goal was to outsource all its functions,” Mr. Khasbulatov said.

Today the restaurants in Russia employ 25,000 people, a number far eclipsed by the businesses in McDonald’s supply chain, which employ 100,000, Mr. Khasbulatov said.

That is successful economic development. Right there.

People are not rational maximisers of von Neumann-Morgenstern utility

Here are two examples:

- At every sandwich shop in Britain (Pret A Manger, Eat, etc), when you attempt to pay for your sandwich you will be asked if you will be eating in or taking the food out of the shop. The reason is that, thanks to the complexities of the UK tax system, the shop is meant to pay VAT if you dine in, but they don’t have to if you take it out.

The shop doesn’t care in the slightest whether you actually eat in or out. So long as they’ve asked you about your intentions, they’re legally covered. The upshot is that for anybody actually intending to eat their sandwich in the shop, the rational thing to do is to say that you’re taking it out and then eat in the shop anyway. If anybody asks why you chose to do so, simply explain that you changed your mind. Since the sandwich shop doesn’t care, the probability of being caught is zero; and since you can always say that you changed your mind even if you were, the cost of being caught is precisely none. Hence, the rational von Neumann-Morgenstern expected utility maximiser should never pay more than the take-out price. But people do …

- When you book cinema tickets online, you have the option of selecting a student discount. Cinemas love online bookings because you then collect your ticket from a machine instead of a person. That means that they’re free to either hire one less person, or put the person saved onto the candy counter. It also means that they can have ticket collection take up less space and expand the candy counter (where all the fat profit margins are located).You do not need to show a student card when collecting your ticket from the machine at the cinema.

You do not need to show a student card when entering the cinema with your ticket. You can, in fact, claim a student discount without any risk of being asked to prove that you are actually a student. But people don’t …

Both of these examples are of price discrimination by a monopolist. In the second example, the Cinema is the discriminator, charging less to students because students, in general, have a lower willingness to spend than non-students. In the first example, the UK government is the discriminator. The people with the lower willingness to pay are those that are prepared to take their food out rather than dine in.

In standard economic theory, both examples should succeed only if a) people are risk averse — which, in general, they are — and b) there is a non-zero chance that a “cheater” will get caught and suffer some loss as a result. Even then, the probability-weighted loss from being caught would need to exceed the probability-weighted gain from successfully “cheating”.

But since the probability of being caught in these examples is zero and, with the sandwich shop, at least, the loss from being caught is also zero, the theory breaks down here.

I suspect that even Loss Aversion, a consequence of Prospect Theory, would fail to explain people’s behaviour here because we are talking about zero-probability events.

I don’t think we can avoid including social norms and ethics to explain them. People have a socially-conditioned aversion to lying (saying that you will take the food out when you really intend to eat in; saying that you’re a student when you’re not) and this is what offsets the gain from the deception. It also pretty clearly depends on the size of the gain relative to some internal scale. A non-student with a low income is more likely to pretend to be a student than someone with a high income.

A blast from the past

Back in June of 1987 (!), the New York Times interviewed Edward W. Kelley Jr. just as he joined the Federal Reserve’s board of governors. How’s this for a quote?:

Q. Mr. Volcker has been considered something of a foot-dragger on bank deregulation. Where do you stand?

A. I’m philosophically in favor. The deregulation we’ve had over the last few years has been highly beneficial and I would favor further deregulation of the financial services industry. But there’s an overriding public interest in making sure the integrity of those types of institutions is maintained. I really do not want to run any meaningful risks that we deregulate at a speed or in a way that would imperil that.

Brilliant!

[Hat tip to my new favourite blog (ok, so I’m two years behind the times), Economics of Contempt]

Doris

Something like 11 years ago, my brother got a dog. She was a border collie – blue australian cattle dog cross (the two most energetic breeds that exist) and, because my brother has always had a knack for naming things, he called her “Doris, the dog.”

A few years ago my brother bought his own place in town and so moved out of the cottage in which he’d lived at Mum and Dad’s place. Doris had always been a country dog and wouldn’t have done well in a small back yard, so he didn’t take her in with him (the cat, named “Cat,” did go). Instead, Doris stayed out with Mum and Dad and my brother would come out to play with her while telling our parents that of course he was there to see them.

Doris was, in many ways, an insane dog. When my parents moved to The Hill seven years ago, she was introduced, most painfully, to the local jumping cactus (more properly called Tiger pear, or scientifically, Opuntia aurantiaca).

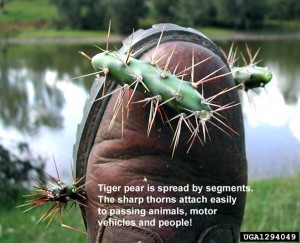

A quick aside. Jumping cactus is a vicious little bugger, because the segments are quite small (often just a centimetre or two) and the spines are fantastically long (two to three centimetres). The spines are barbed and the plant segments attached to each other by the loosest of connections, so the faintest possible touch will lead to one of them sticking in your trousers, shoes, foot or what have you. The barb on the spines (like a fish hook) means that they will not come out simply when pulled, but need to be ripped out in a manner that, if it’s your foot it’s emerging from, will bring tears to your eyes. Here’s a picture of the stuff attached to somebody’s boot:

Tiger pear is native to South America and was stupidly brought to Australia in the 1800s as an “ornamental garden plant.” It is now all over south-east Queensland and north-east New South Wales to the west of the Great Dividing Range and threatens to move over most of south-east Australia.

[The map comes from weeds.com.au]

Anyway. When my parents first moved to The Hill, poor Doris managed to step on some of the ghastly stuff and somebody — I don’t remember who; probably Mum — had the joy of holding her down and tearing the spines out of her foot with a pair of pliers. Doris was always a smart dog and didn’t blame the humans for this pain. She knew what was responsible and she must have vowed, in her little doggie brain, to take action.

From that day on, at every opportunity, she would pad around the top of the hill looking for jumping cactus and, upon discovering a patch, would settle down and eat them. I should stress that this ought to be utterly impossible. The spines, as mentioned earlier, are at least an inch long. There is no way that Doris could have eaten them without sticking herself in the mouth with an awful collection of fish-hooked spines. But she did it. Somehow, she did it, and she did it every time my mother went to work in the garden. Which is a lot. A lot.

She also believed firmly in attacking snakes, for exactly the same reason. Doris was bitten by snakes on, I think, three occasions on The Hill. She should have died from all three of them. She certainly should have died from the one that caused the skin on her stomach to die and rot away, leaving her innards exposed to the air. My parents are not heartless; they took her in to the vet, but the nice lady explained that full treatment would cost thousands of dollars and my parents are not made of money and, besides, they both grew up on and now, again, lived themselves on a farm. Things sometimes die on a farm. So they took Doris home with the hole in her stomach and were especially nice to her. Doris survived. Doris just kept the wound clean by licking it around the clock and it gradually grew over. In the end, you couldn’t see any scars and her hair grew back over the whole area. She got her own back, mind you. Every summer when the snakes came out, she wouldn’t back away, but would attack them; and I do mean attack. She’d grab and toss them, shaking her head to try to crack a spine or some such. Mum and Dad used to discover dead snakes on the front lawn, left as presents.

The point, as you might imagine, is that Doris was an absurdly tough dog. This is not particularly unusual for Australian Cattle Dogs. You should hear some of the stories about my uncle’s dog, a red aussie, called — well, what did you expect? — “Red.” But this isn’t a post about Red. It’s about Doris.

Doris loved to please. It was in her nature. The instinct of both the Cattle Dog and the Border Collie is to run, to chase, to track and to herd. For both, the link to their humans is near absolute. Doris was never trained as a proper cattle dog (much to her frustration when my parents started breeding a few cattle), but she loved chasing balls. She really loved chasing balls. When she got tired from the chasing, she loved taking the ball into the shade and chewing it to pieces. No doubt it was to keep her in shape for the next round of jumping cactus destruction. Occasionally my mother would buy one of those expensive, “indestructible” balls for her. I think the longest one of them lasted was 48 hours. No, the only way to preserve a ball was to stick it in a bag out of her reach.

Doris wasn’t utterly indestructible, mind you. Possibly because of some inherited condition, or possibly because of the string of snake bites, she suffered from a kind of arthritis. She’d be stiff getting up in the morning and she might take a little while to warm up. But once she was going, there was nothing stopping her.

Oh, the craziness. I forgot the craziness. Doris never quite understood storms. I don’t just mean that she was scared of thunder. Lots of dogs are scared of thunder. Doris thought that the thunder and lightning were some enormous, angry animal. Her fight-or-flight mode was often a random switch between the two. Sometimes she would run around the yard trying to bite the lightning in the distance; sometimes she would rip open the screen door and slink inside to hide in the kitchen. The first of these was just a source of laughter for Mum and Dad until Mum discovered that the same logic she’d applied to jumping cactus and snakes also applied to electricity. For some reason a wire had become exposed close to Doris’ kennel and was crackling a little. Doris tried to bite it. Fortunately, that didn’t kill her either. Tough.

Anyway, Daniela and I were back visiting over Christmas. My mum’s brother and his family came in from Roma the day after Boxing Day and we all played some backyard cricket. Doris, naturally, represented two-thirds of the fielding team. I was on The Hill for a good two weeks out of my three in Australia and I threw the ball for Doris every day. She’s a great dog. She was a great dog. This morning I woke up to this email from Mum:

A sad day. Doris died this morning. It is Australia Day so a holiday. I was mowing the lawn early and she was fine; chasing the mower trying to bite the wheel – she got it too! – I threw the ball for her a few times as I mowed. Your Dad and I were having coffee on the verandah at about 9am and she was lying on her mat under the family room window where she always lies, when I looked at her and she looked funny. Eyes open but not there. And that was it I guess the heart just stopped. No struggle, no noise, didn’t look distressed, just gone. We waited for an hour or so, I kept thinking she might not really have died but be having a fit as she sometimes does and then rang James. He was lovely and came out and helped bury her down under a big old ironbark tree overlooking the road.

On the upside, she didn’t appear to suffer at all. If I could eat chops the night before, chase a lawn mower an hour earlier and then lie down in the sun on the verandah surrounded by loved ones before I die – that would be about as good a way to go as any.

James stayed for the rest of the day and we’re all fine, just sad. She was 11 years old and such a good dog for out here. I keep thinking I can hear her outside. We’ll miss her for a long time.

Which is just about the most awful news I could possibly have received today. Doris was never my dog. I lived in the UK for seven of her eleven years and in Brisbane (two or three hours away) for the rest of them. But I’m going to miss her enormously. Rudyard Kipling wrote about this, many years ago. He was one of my grandmother’s favourite authors, and my mother’s too.

The Power Of The Dog

Rudyard KiplingThere is sorrow enough in the natural way

From men and women to fill our day;

And when we are certain of sorrow in store,

Why do we always arrange for more?

Brothers and Sisters, I bid you beware

Of giving your heart to a dog to tear.Buy a pup and your money will buy

Love unflinching that cannot lie–

Perfect passion and worship fed

By a kick in the ribs or a pat on the head.

Nevertheless it is hardly fair

To risk your heart for a dog to tear.When the fourteen years which Nature permits

Are closing in asthma, or tumour, or fits,

And the vet’s unspoken prescription runs

To lethal chambers or loaded guns,

Then you will find–it’s your own affair–

But…you’ve given your heart for a dog to tear.When the body that lived at your single will,

With its whimper of welcome, is stilled (how still!);

When the spirit that answered your every mood

Is gone–wherever it goes–for good,

You will discover how much you care,

And will give your heart for the dog to tear.We’ve sorrow enough in the natural way,

When it comes to burying Christian clay.

Our loves are not given, but only lent,

At compound interest of cent per cent.

Though it is not always the case, I believe,

That the longer we’ve kept ’em, the more do we grieve:

For, when debts are payable, right or wrong,

A short-time loan is as bad as a long–

So why in Heaven (before we are there)

Should we give our hearts to a dog to tear?

So long, Doris. It won’t be the same without you.

Obama’s (i.e. The Volcker) bank plan

Those of us who aren’t American but still follow U.S. politics were quietly giggling (okay, openly guffawing) into our latte’s last week when Scott Brown won the special election to replace the late Ted Kennedy. The Daily Show’s take on the whole affair (I think it was broadcast the night before the election day) was spot on and I urge anyone with the capability to hunt down that episode. In short, the Democrat’s handling of the event is a classic example of why the word clusterfuck was invented. What in blazes they now intend to do in passing any reasonable kind of reform in health-care (and the ideas on the table weren’t really all that reasonable to start with) is beyond me.

Anyway. I tip my hat to the newest federal Senator in the United States for an expertly handled campaign.

I was then surprised to (finally) see some equally smart politics from the White House in the form of Obama publically supporting the banking regulation ideas of former Fed chair and octogenarian, Paul Volcker.

The White House had already been making noises about imposing a fee on financial institutions to recoup any losses in TARP. TARP, if you remember, is the US$700 billion officially set aside under president Bush Jr. to help the finance industry weather the storm. Of course, a large fraction of TARP was diverted to help the car (that’s “auto” for any Americans in the audience) industry and not all assistance to the financial industry was included in TARP. Still, it’s the closest thing to an easy target with a pronounceable name. If you care, you can read my incredibly brief thoughts on the levy here and, more importantly, here.

But the Volcker plan is an entirely different kettle of fish and can be boiled down to a simple and beautiful phrase: “Too big to fail is just too big.”

It calls for constraints on the scope and the size of US banks. It seeks to ban proprietary trading at institutions that hold retail deposits. It’s an armchair commentator’s wet dream come true! It’s also, unfortunately, staggeringly unlikely to ever become reality. There are two reasons for this.

First, as expertly described by the Economics of Contempt, the White House has no intention of pushing this through anyway. Instead, it was …

… a fairly transparent political stunt — the White House needed to do something to take the media’s focus off of health care 24/7, so they flew in Volcker and announced some proposals that sound good to the media. The two Senate staffers I talk to regularly both said their offices were basically ignoring Obama’s proposals, because even if the White House fights for them (which they won’t), Chris Dodd has no intention of inserting them into his committee’s bill. I like how some people think Obama’s proposals represent a fundamental turning point on financial reform, because….well, clearly this is their first rodeo. (Hence the uber-quixotic language they use to describe financial reform.)

[Update: Just to clarify, when I said Obama’s announcement was a “fairly transparent political stunt,” I wasn’t criticizing the Obama administration. We live in a political world, and political stunts are often useful. If I were Rahm Emanuel, I’d be a dick have done the same thing. I think it was probably a savvy move, and if health care reform ends up passing, then it was worth it.]

Second, the U.S. Supreme Court, in the second move in the space of a week to leave the America-watchers of the world chuckling, decided to reverse decades of precedent and assert that when it came to political speech, corporations, unions and other groups of individuals have more power than individuals. Not only can corporations, unions and the like directly fund political campaigns, but unlike individuals, they are subject to no limit on their donations. It’s great. You’re going to end up seeing major political events sponsored by Pepsi. You’re going to have unlimited funding available to opponents of any politician that does anything that runs contrary to a company that employs people in his or her district or state. In short, you will never, ever again see anything serious passed in an election year in the United States unless it has not just bipartisan, but unanimous support.

So, no, as much as I like what Obama said, I don’t think it’ll ever become law. It certainly won’t in 2010.