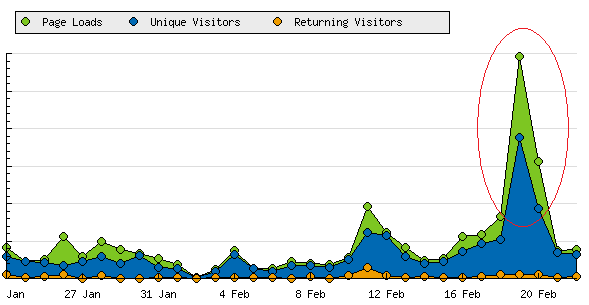

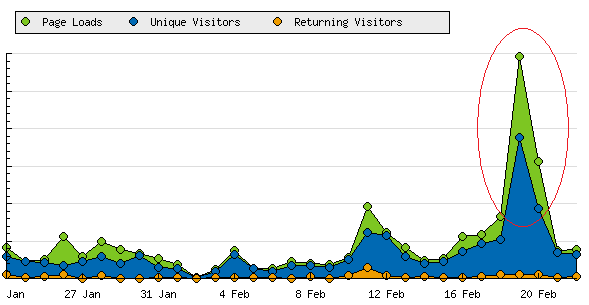

… when Mark Thoma links to you in the midst of one of his daily “Links For” posts:

(Side Note: I’ve alway’s liked Economist’s View. Mark provides a truely terrifying aggregation of econo-blogo-thought.)

Research Economist at the Bank of England

… when Mark Thoma links to you in the midst of one of his daily “Links For” posts:

(Side Note: I’ve alway’s liked Economist’s View. Mark provides a truely terrifying aggregation of econo-blogo-thought.)

Writing in Friday’s FT, Jamie Whyte argues that Gordon Brown is wrong to think that regulating bankers’ bonuses to stop the culture of short-term thinking will avoid future financial crises. He writes:

[I]magine you are the manager of a lottery company. Your job is similar to a banker’s. You sell tickets (make loans) that have a certain probability of winning a prize (of defaulting). To ensure long-run profits, you must set a price for the tickets (charge a rate of interest) that is sufficient to pay out the lottery winnings (cover the cost of defaulting borrowers).

But suppose you were a greedy lottery company manager, concerned more with your own bonus than with your shareholders’ interests. Here is a trick you might play. Offer jackpots, ticket odds and ticket prices that in effect give your customers money. For example, offer $1 tickets with a one-in-5m chance of winning a $10m prize. A one-in-5m chance of winning $10m is worth $2 . So each ticket represents a gift of $1 to its purchaser.

With such an attractive “customer value proposition” you would leave your competitors for dead. And if you limited ticket sales to, say, 1m a year, the chances are no one would win the prize. In most years you will earn $1m in ticket sales and pay nothing in prizes. When someone finally wins the $10m prize, and your company collapses, that will be a problem for shareholders and creditors; you will probably have pocketed a few nice bonuses already.

To prevent such wickedness, Mr Brown may insist that lottery managers be paid bonuses on the basis of long-term profits: five years’, let us say. No problem: simply set the prize at $100m and the chance of winning at one in 50m. Then you will be unlucky if anyone wins in a five-year period, and you can be confident of walking away with a fat bonus.

This is why, even if Mr Brown were right that short-term bonus plans caused the financial crisis, his proposed remedy would not help. Whatever time frame he mandates, it will always be too short. For, like lottery managers, bank managers can manipulate the “risk profile” of the bank so that large losses, although inevitable in the long run, are unlikely during the mandated period.

I like Mr. Whyte’s analogy, but as far as I can see, there are three problems in his logic. For the sake of some numbers to talk about, I’ll consider the idea of a five-year delay in high-end bankers having access to their bonuses.

First, he’s missing the fact that for his lottery company to offer a prize of $100 million, it’s going to need some backers with much deeper pockets than if his prize is only $10 million. Whyte quite correctly points out that risk has been mispriced, but provided that it’s got some price, scaling up without a larger customer pool (the equivalent of increasing the leverage of your bank) must come with extra costs. Even if the wholesale market is willing to stand behind you, one option is to increase the duration until the size needed to outflank it would require bank mergers that would run foul of competition law.

Second, a key feature long-term bonuses is that they accumulate. If bonuses are awarded annually but placed into escrow for five years, then even if the bad event doesn’t happen until year 10, there will be five years of bonuses available for claw-back. All the bankers are currently giving up one year of bonuses. By putting bonuses to one side, we magnify the value at risk faced by the bankers themselves.

Third, we need to recognise that nobdy lives forever, and while one year might not be so long when measured against a career, five years is a serious block of time. The reputational effects of any failure would be increased and, I hope, institutional memory would be improved.

As I say, I agree that a mispricing of risk lies at the heart of the credit crisis. I simply disagree with Mr. Whyte on why it occured. I’m not sure why he thinks it occured, but I think that part of the cause is the short-term nature of bank incentives.

Via a mysterious blogger some describe as a grumpy, toothless old man, I bring you: ?olcats (English translations of Eastern Bloc Lolcats). It’s important that you click through to see the images, but here are a few captions to whet your appetite:

From the latest press release of the US Federal Reserve Board:

The central tendency of FOMC participants’ longer-run projections, submitted for the Committee’s January 27-28 meeting, were:

- 2.5 to 2.7 percent growth in real gross domestic output

- 4.8 to 5.0 percent unemployment

- 1.7 to 2.0 percent inflation, as measured by the price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE).

Most participants judged that a longer-run PCE inflation rate of 2 percent would be consistent with the dual mandate; others indicated that 1-1/2 or 1-3/4 percent inflation would be appropriate.

Speaking earlier in the day, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke observed:

These longer-term projections will inform the public of the Committee participants’ estimates of the rate of growth of output and the unemployment rate that appear to be sustainable in the long run in the United States, taking into account important influences such as the trend growth rates of productivity and the labor force, improvements in worker education and skills, the efficiency of the labor market at matching workers and jobs, government policies affecting technological development or the labor market, and other factors. The longer-term projections of inflation may be interpreted, in turn, as the rate of inflation that FOMC participants see as most consistent with the dual mandate given to it by the Congress–that is, the rate of inflation that promotes maximum sustainable employment while also delivering reasonable price stability.

(Hat tip: Calculated Risk)

Via Jason Kottke, I give you the true origins of breakdancing – Soviet military dancers (the glory starts around 1:00):

For comparison, the original music video for “It’s like that”:

That is all.

The Phillips Curve is an empirical observation that inflation and unemployment seem to be inversely related; when one is high, the other tends to be low. It was identified by William Phillips in a 1958 paper and very rapidly entered into economic theory, where it was thought of as a basic law of macroeconomics. The 1970s produced two significant blows to the idea. Theoretically, the Lucas critique convinced pretty much everyone that you could not make policy decisions based purely on historical data (i.e. without considering that people would adjust their expectations of the future when your policy was announced). Empirically, the emergence of stagflation demonstrated that you could have both high inflation and high unemployment at the same time.

Modern Keynesian thought – on which the assumed efficacy of monetary policy rests – still proposes a short-run Phillips curve based on the idea that prices (or at least aggregate prices) are “sticky.” The New Keynesian Phillips Curve (NKPC) generally looks like this:

Where is the (natural) log deviation – that is, the percentage deviation – of output from its long-run, full-employment trend and

and

are parameters. Notice that (unlike the original Phillips curve), it is forward looking. There are criticisms of the NKPC, but they are mostly about how it is derived rather than its existence.

What follows is a derivation of the standard New Keynesian Phillips Curve using Calvo pricing, based on notes from Kevin Sheedy‘s EC522 at LSE. I’m putting it after this vile “more” tag because it’s quite long and of no interest to 99% of the planet.

Continue reading “Deriving the New Keynesian Phillips Curve (NKPC) with Calvo pricing”

By popular demand (well, one person asked me), I’ve installed WP-Print – a WordPress plugin that will allow you, valued readers, to see a printer-friendly version of any post or page on this blog.

Every post and page now has a link at the top that takes you to the printer-friendly version of that post or page. If you live-and-die by the URI bar, it’s the usual address with “/print/” at the end.

Let me know if you have any problems.

I’ve installed the Latex for WordPress plugin, so now I can freak people out by writing stuff like this:

$$P_{it}^{\ast }=\left( \frac{\gamma }{\gamma -1}\right) ce^{s_{it}}$$

John Hempton has an excellent post on valuing the assets on banks’ balance sheets and whether banks are solvent. He starts with a simple summary of where we are:

We have a lot of pools of bank assets (pools of loans) which have the following properties:

- The assets sit on the bank’s balance sheet with a value of 90 – meaning they have either being marked down to 90 (say mark to mythical market or model) or they have 10 in provisions for losses against them.

- The same assets when they run off might actually make 75 – meaning if you run them to maturity or default the bank will – discounted at a low rate – recover 75 cents in the dollar on value.

- The same assets if sold in the market (which does exist if you wish to discover the price) trade at 50 cents in the dollar.

The banks are thus under-reserved on an “held to maturity” basis. Heavily under-reserved.

He then gives another explanation (on top of the putting-Humpty-Dumpty-back-together-again idea I mentioned previously) of why the market price is so far below the value that comes out of standard asset pricing:

Before you go any further you might wonder why it is possible that loans that will recover 75 trade at 50? Well its sort of obvious – in that I said that they recover 75 if the recoveries are discounted at a low rate. If I am going to buy such a loan I probably want 15% per annum return on equity.

The loan initially yielded say 5%. If I buy it at 50 I get a running yield of 10% – but say 15% of the loans are not actually paying that yield – so my running yield is 8.5%. I will get 75-80c on them in the end – and so there is another 25cents to be made – but that will be booked with an average duration of 5 years – so another 5% per year. At 50 cents in the dollar the yield to maturity on those bad assets is about 15% even though the assets are “bought cheap”. That is not enough for a hedge fund to be really interested – though if they could borrow to buy those assets they might be fun. The only problem is that the funding to buy the assets is either unavailable or if available with nasty covenants and a high price. Essentially the 75/50 difference is an artefact of the crisis and the unavailability of funding.

The difference between the yield to maturity value of a loan and its market value is extremely wide. The difference arises because you can’t eaily borrow to fund the loans – and my yield to maturity value is measured using traditional (low) costs of funds and market values loans based on their actual cost of funds (very high because of the crisis).

The rest of Hempton’s piece speaks about various definitions of solvency, whether (US) banks meet each of those definitions and points out the vagaries of the plan recently put forward by Geithner. It’s all well worth reading.

One of the other important bits:

Few banks would meet capital adequacy standards. Given the penalty for even appearing as if there was a chance that you would not meet capital adequacy standards is death (see WaMu and Wachovia) and this is a self-assessed exam, banks can be expected not to tell the truth.

(It was Warren Buffett who first – at least to my hearing – described financial accounts as a self-assessed exam for which the penalty for failure is death. I think he was talking about insurance companies – but the idea is the same. Truth is not expected.)

The 2008:Q4 figures for the EU-countries came out recently. It’s not pretty. But a regular recession is nothing compared to what might be coming.

In the understatement of the day, Tyler Cowen writes:

It’s a little scary:

Stephen Jen, currency chief at Morgan Stanley, said Eastern Europe has borrowed $1.7 trillion abroad, much on short-term maturities. It must repay – or roll over – $400bn this year, equal to a third of the region’s GDP. Good luck. The credit window has slammed shut….

“This is the largest run on a currency in history,” said Mr Jen.

The naked capitalism entry that Tyler points us to is itself a wrapper for this article in the Telegraph. It’s a little hyperbolic, but if the facts it’s listing are correct, not overly. Here are a couple of paragraphs from it:

Whether it takes months, or just weeks, the world is going to discover that Europe’s financial system is sunk, and that there is no EU Federal Reserve yet ready to act as a lender of last resort or to flood the markets with emergency stimulus.

Under a “Taylor Rule” analysis, the European Central Bank already needs to cut rates to zero and then purchase bonds and Pfandbriefe on a huge scale. It is constrained by geopolitics – a German-Dutch veto – and the Maastricht Treaty.

To this mess we can add the case of Ireland. Simon Johnson, writing at The Baseline Scenario, observes:

Look at the latest Credit Default Swap spreads for European sovereigns (these are the data from yesterday’s close). As we’ve discussed here before, CDS are not a perfect measure of default probability but they tell you where things are going – and changes within an asset class (like European sovereigns) are often informative.

European CDS have been relatively stable – albeit at dangerously high levels – for the past month or so. But now Ireland has moved up sharply (the green line in the chart). We’ve covered Ireland’s problems here before (banking, fiscal and – big time – real estate); type “Ireland” into our Search box for more.

Interesting times …