The UN Office on Drugs and Crime has just released their latest report, including details on opium production in Afghanistan. Here are a few of the statistics:

| 2006 | Year-on-year difference | 2007 | |

| Net opium poppy cultivation | 165,000 ha | +17% | 193,000 ha |

| In per cent of agricultural land | 3.65% | 4.27% | |

| Eradication | 15,300 ha | +24% | 19,047 ha |

| Weighted average opium yield | 37.0 kg/ha | +15% | 42.5 kg/ha |

| Potential production of opium | 6,100 mt | +34% | 8,200 mt |

| In percent of global production | 92% | 93% | |

| Number of households involved in opium cultivation | 448,000 | +14% | 509,000 |

| Afghanistan GDP | US$ 6.7 billion | +12% | US$ 7.5 billion |

| Afghanistan GDP per capita | US$ 290 | +7% | US$ 310 |

| Total farm-gate value of opium in per cent of GDP | 11% | 13% | |

| Indicative gross income from opium per ha | US$ 4,600 | +13% | US$ 5,200 |

| Indicative gross income from wheat per ha | US$ 530 | +3% | US$ 546 |

Make sure you read that correctly: Area under cultivation is up 17% and area eradicated is up 24%. That might make you think (as it did me originally) that the total area producing is down, but you’d be wrong … the 17% was on a huge area and the 24% was on a tiny area. Net productive area went from 149,700 ha to 173,953 ha — an increase of 16%. On top of that, yield per hectare is up 15%, so overall output is up 34%.

GDP/capita is US$310 and — assuming that your crop isn’t eradicated by the US — income from growing opium poppy is US$5,200 per hectare (or $US2,100 per acre). That’s an awfully big incentive. On top of all that, I understand that one of the big appeals of growing poppy is that opium has an extremely high value per unit volume and per unit weight, which are important considerations for a farmer living in a country with very low-quality and high-cost transportation infrastructure.

I wonder how they got the yield up so quickly? Was it improved infrastructure (watering systems), the dedication of better quality land to poppy cultivation, better inputs (fertilizer) or something else? Whatever the answer, that looks to me to be fairly serious evidence of planned investment. These farmers are not just doing this on the side.

This would be a good time to point readers to this opinion piece by Willem Buiter (blog, NBER, LSE) . The discussion by other FT contributors is also well worth reading. Here’s a taster from the first paragraph so you know what he’s saying:

As an economist with a strong commitment to personal liberty and responsibility, my preference would be to see all illegal drugs legalised. The only exception would be substances whose consumption leads to behaviour likely to cause material harm to others.

Further update (30 Aug):

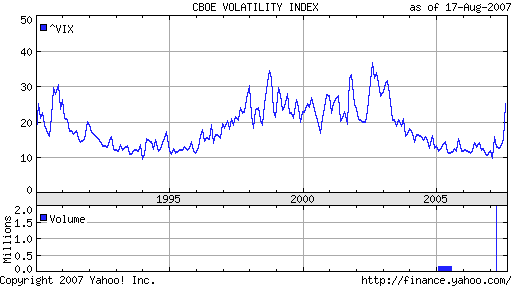

The Economist has produced this graph to illustrate world opium production since 1990:

[ Image removed because it was messing with my site. Click on the Economist link to see it ]