With forecasts for annualised U.S. real GDP growth in 2008:Q4 as low as -6% (!) and seriously smart people worrying about next year, both from the left and the right, you really do have to wonder how ugly it’s going to get. Looking at the world as a whole is a recipe for staying under the covers tomorrow morning, too.

Bush does the right thing

The US$700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program, otherwise known as the mother of all pork, did have one redeeming feature: It came in tranches. The first US$350 billion were directly accessible (some of it needed a signature from the president), but the last US$350 billion needs congressional approval. With just 10 weeks to go in his Presidency and every company big enough to hire a lobbiest bashing on the doors for a piece of the action, George W. Bush has done the right thing: He’s deciced to not ask for the last 350. If soon-to-be-President Obama wants to tap it, it’s up to him.

The Bush administration told congressional aides it won’t ask lawmakers to release $350 billion remaining as part of the $700 billion U.S. financial- rescue package, people familiar with the matter said.

…

The Treasury Department has committed $290 billion, or about 83 percent of the total allocated so far in a program Congress enacted last month to inject capital into a wide spectrum of banks and American International Group Inc. The U.S. invested $125 billion in nine major banks, including Citigroup Inc. and Wells Fargo & Co. and plans to buy an additional $125 billion in preferred shares of smaller lenders.

…

Paulson told the Wall Street Journal today he is unlikely to use what remains of the package, estimated at $410 billion, unless a need arises.“I’m not going to be looking to start up new things unless they’re necessary, unless they make great sense,” Paulson said. “I want to preserve the firepower, the flexibility we have now and those that come after us will have.”

Update: I don’t mean to suggest that the money shouldn’t be spent. Maybe it should. Professor Krugman, for one, might argue that it ought to be spent as part of a stimulus package. I just think that it’s correct for Bush to pass on deciding how to spend it. His moral authority as an economic leader was gone some time ago. Paulson’s flip-flopping, even if what he has moved to is the better plan, demonstrates the same for him. America will – I suspect – benefit from being forced to take a breather in their cries for help. Let the new team think about the whole mess carefully and then take up the responsibility handed to them.

Another update: The anonymous authors at Free Exchange aren’t so sure it’s a good idea:

It is, in effect, calling time-out on the rescue until Barack Obama is sworn in, and even then there will be a delay while funds are requested and authorised. Meanwhile, Congress has all but decided not to pursue a stimulus bill during the lame duck session. The legislature is taking up discussions on an automaker bail-out, but given resistance to a rescue among Republicans and conservative Democrats, it seems clear that any bill signed into law during the lame duck will be quite weak.

Now, Ben Bernanke will remain on duty right through the inauguration. There’s still an executive branch, and there are still plenty of international policy makers working to stabilise the global financial system. But in a very real sense, America is going to coast on its current economic policies for the next two (and in practice, three) months. I’m not sure this is a good idea, particularly given the critical nature of the holiday shopping season. By all accounts, consumers are locking up their piggy banks at the moment. A disastrous shopping season will probably mean a wave of post-holiday failures among retailers, which will, in turn, mean lay-offs (as well as pain for exporters to America).

Yes, it’s only three months, but three months is a long time for people and businesses struggling to pay bills. And if the economic situation deteriorates over that span, then the government may well feel pressured to pass a much larger and more expensive stimulus package in the spring.

I’m not convinced. I do note that, as Paul Krugman points out, it’s difficult to have too large a fiscal stimulus in this environment. I also think that we might benefit from backing off a little bit and abandoning the idea that America and the world at large can somehow escape the recession. It needs to sink in.

More on the shift from Republican to Democrat

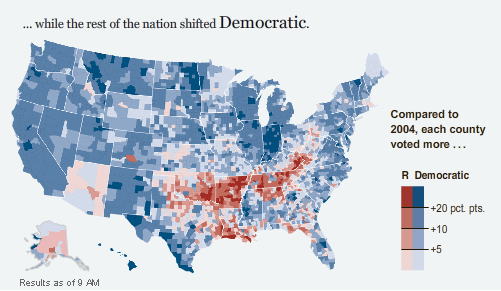

Brad Delong observes that there is a clear regional exception to the idea of a broad shift in the vote from the Republicans to the Democrats (the original scatterplot comes from Andrew Gelman):

Paul Krugman takes it a bit further, emphasising this beauty of a map (I’m not sure of the source. Probably the NY Times?):

The shifts to the Republicans in Arizona and Alaska and to the Democrats in Illinois and Delaware are clearly down to the candidates coming from those states. I’m a little surprised at the strength of the Republican shift in southern Louisiana. One might have thought that with the memory of Hurricane Katrina they would have moved blue. Perhaps the administration’s management of Hurricane Gustav was seen as successful? The Oklahoma-Arkansas-Tennessee shift is presumably McCain’s “real America.” I’d love to see a demographic breakdown of the vote in those states.

Almost immediate update:

dbt on Brad Delong’s blog points out the obvious about Louisiana:

Don’t lump Louisiana into that. The changes there are demographic, not electoral.

Which of course must be the explanation. Southern Louisiana didn’t turn red because of the success of the handling of Gustav; it turned red because of the failure to handle Katrina – vast numbers of black Americans were forced out and haven’t come back.

Endogenous Growth Theory

Following on from yesterday, I thought I’d give a one-paragraph summary of how economics tends to think about long-term, or steady-state, growth. I say long-term because the Solow growth model does a remarkable job of explaining medium-term growth through the accumulation of factor inputs like capital. Just ask Alwyn Young.

In the long run, economic growth is about innovation. Think of ideas as intermediate goods. All intermediate goods get combined to produce the final good. Innovation can be the invention of a new intermediate good or the improvement in the quality of an existing one. Profits to the innovator come from a monopoly in producing their intermediate good. The monopoly might be permanent, for a fixed and known period or for a stochastic period of time. Intellectual property laws are assumed to be costless and perfect in their enforcement. The cost of innovation is a function of the number of existing intermediate goods (i.e. the number of existing ideas). Dynamic equilibrium comes when the expected present discounted value of holding the monopoly equals the cost of innovation: if the E[PDV] is higher than the cost of innovation, money flows into innovation and visa versa. Continual steady-state growth ensues.

It’s by no means a perfect story. Here are four of my currently favourite short-comings:

- The models have no real clue on how to represent the cost of innovation. It’s commonly believed that the cost of innovation must increase, even in real terms, the more we innovate – a sort of “fishing out” effect – but we lack anything more finessed than that.

- I’m not aware of anything that tries to model the emergence of ground-breaking discoveries that change the way that the economy works (flight, computers) rather than simply new types of product (iPhone) or improved versions of existing products (iPhone 3G). In essence, it seems important to me that a model of growth include the concept of infrastructure.

- I’m also not aware of anything that looks seriously at network effects in either the innovation process (Berkley + Stanford + Silicon Valley = innovation) or in the adoption of new stuff. The idea of increasing returns to scale and economic geography has been explored extensively by the latest recipient of the Nobel prize for economics (the key paper is here), but I’m not sure that it has been incorporated into formal models of growth.

- Finally, I again don’t know of anything that looks at how the institutional framework affects the innovation process itself (except by determining the length of the monopoly). For example, I am unaware of any work emphasising the trade-off between promoting innovation through intellectual property rights and hampering innovation through the tragedy of the anticommons.

Paul Krugman wins the Nobel (updated)

There is no doubt in my mind that Professor Krugman deserves this, but who doesn’t think that this is just a little bit of an “I told you so” from Sweden to the USA?

Update: Alex Tabarrok gives a simple summary of New Trade Theory. Do read Tyler Cowen for a summary of Paul Krugman’s work, his more esoteric writing and some analysis of the award itself.

I have to say I did not expect him to win until Bush left office, as I thought the Swedes wanted the resulting discussion to focus on Paul’s academic work rather than on issues of politics. So I am surprised by the timing but not by the choice.

…

This was definitely a “real world” pick and a nod in the direction of economists who are engaged in policy analysis and writing for the broader public. Krugman is a solo winner and solo winners are becoming increasingly rare. That is the real statement here, namely that Krugman deserves his own prize, all to himself. This could easily have been a joint prize, given to other trade figures as well, but in handing it out solo I believe the committee is a) stressing Krugman’s work in economic geography, and b) stressing the importance of relevance for economics

Formalism and synthesis of methodology

Robert Gibbons [MIT] wrote, in a 2004 essay:

When I first read Coase’s (1984: 230) description of the collected works of the old-school institutionalists – as “a mass of descriptive material waiting for a theory, or a fire” – I thought it was (a) hysterically funny and (b) surely dead-on (even though I had not read this work). Sometime later, I encountered Krugman’s (1995: 27) assertion that “Like it or not, … the influence of ideas that have not been embalmed in models soon decays.” I think my reaction to Krugman was almost as enthusiastic as my reaction to Coase, although I hope the word “embalmed” gave me at least some pause. But then I made it to Krugman’s contention that a prominent model in economic geography “was the one piece of a heterodox framework that could easily be handled with orthodox methods, and so it attracted research out of all proportion to its considerable merits” (p. 54). At this point, I stopped reading and started trying to think.

This is really important, fundamental stuff. I’ve been interested in it for a while (e.g. my previous thoughts on “mainstream” economics and the use of mathematics in economics). Beyond the movement of economics as a discipline towards formal (i.e. mathematical) models as a methodology, there is even a movement to certain types or styles of model. See, for example, the summary – and the warnings given – by Olivier Blanchard [MIT] regarding methodology in his recent paper “The State of Macro“:

That there has been convergence in vision may be controversial. That there has been convergence in methodology is not: Macroeconomic articles, whether they be about theory or facts, look very similar to each other in structure, and very different from the way they did thirty years ago.

…

[M]uch of the work in macro in the 1960s and 1970s consisted of ignoring uncertainty, reducing problems to 2×2 differential systems, and then drawing an elegant phase diagram. There was no appealing alternative – as anybody who has spent time using Cramer’s rule on 3×3 systems knows too well. Macro was largely an art, and only a few artists did it well. Today, that technological constraint is simply gone. With the development of stochastic dynamic programming methods, and the advent of software such as Dynare – a set of programs which allows one to solve and estimate non-linear models under rational expectations – one can specify large dynamic models and solve them nearly at the touch of a button.

…

Today, macro-econometrics is mainly concerned with system estimation … Systems, characterized by a set of structural parameters, are typically estimated as a whole … Because of the difficulty of finding good instruments when estimating macro relations, equation-by-equation estimation has taken a back seat – probably too much of a back seat

…

DSGE models have become ubiquitous. Dozens of teams of researchers are involved in their construction. Nearly every central bank has one, or wants to have one. They are used to evaluate policy rules, to do conditional forecasting, or even sometimes to do actual forecasting. There is little question that they represent an impressive achievement. But they also have obvious flaws. This may be a case in which technology has run ahead of our ability to use it, or at least to use it best:

- The mapping of structural parameters to the coefficients of the reduced form of the model is highly non linear. Near non-identification is frequent, with different sets of parameters yielding nearly the same value for the likelihood function – which is why pure maximum likelihood is nearly never used … The use of additional information, as embodied in Bayesian priors, is clearly conceptually the right approach. But, in practice, the approach has become rather formulaic and hypocritical.

- Current theory can only deliver so much. One of the principles underlying DSGEs is that, in contrast to the previous generation of models, all dynamics must be derived from first principles. The main motivation is that only under these conditions, can welfare analysis be performed. A general characteristic of the data, however, is that the adjustment of quantities to shocks appears slower than implied by our standard benchmark models. Reconciling the theory with the data has led to a lot of unconvincing reverse engineering

…

This way of proceeding is clearly wrong-headed: First, such additional assumptions should be introduced in a model only if they have independent empirical support … Second, it is clear that heterogeneity and aggregation can lead to aggregate dynamics which have little apparent relation to individual dynamics.

There are, of course and as always, more heterodox criticisms of the current synthesis of macroeconomic methodology. See, for example, the book “Post Walrasian Macroeconomics: Beyond the Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium Model” edited by David Colander.

I’m not sure where all of that leaves us, but it makes you think …

(Hat tip: Tyler Cowen)

Streuth!

Note to self: When commenting on somebody’s opinion, recognise that they may notice what you say.

Entry Page Time: 16th February 2008 15:57:39

Browser: Firefox 2.0.0

Location: Princeton, New Jersey, United States

Hostname: vpn1-client-a41.princeton.edu

Entry page: Paul Krugman: Hanrahan of the Econ-Blogosphere

Referring URL: krugman.dblogs.nytimes.com/wp-admin/index.php

Paul Krugman: Hanrahan of the Econ-Blogosphere

I’ve got a lot of time for Paul Krugman. People just love to hate the guy, or at least dismiss him as a crank and wonder what he’s going to do when Mr. Bush moves back to Texas, but the man was – for years! – practically the lone beacon of criticism of the Whitehouse in a country that seems to want to beatify its presidents. You can debate the good and bad points of the W. Bush presidency all you like, but the fact remains that America is a country that doesn’t like dissing their sitting president. It seems to make them feel dirty or “unAmerican” or something. Try asking the Poms to lay off their P.M. for a week.

Anyway, this latest piece by Prof. Krugman got me thinking:

But the plunge in consumer confidence in recent weeks is pretty startling. The chart below shows the University of Michigan index; consumer confidence is now lower than it ever was during the 2001 recession and aftermath, and close to its worst levels during the early 90s, when the unemployment rate went well above 7 percent.

Bit by bit, the evidence is mounting that the wheels are coming off this economy.

I don’t want to dispute the facts of the brief post, just the sentiment. The “wheels are coming off”? Come on. The U.S. is probably entering, if it hasn’t already entered, a recession. That is not the wheels coming off the economy. That is a perfectly normal phenomenon and Professor Krugman knows it. It’s also arguably a necessary phenomenon and I’d be stunned if Professor Krugman didn’t know those arguments. If you want an example of an economy with the wheels off, look at Zimbabwe. Now that, to mix our tired metaphors, is a train wreck.

All of which reminded me of a famous (in Australia, anyway) poem by Patrick Hartigan (1878-1952) writing under the pseudonym of John O’Brien:

Said Hanrahan

“We’ll all be rooned,” said Hanrahan,

In accents most forlorn,

Outside the church, ere Mass began,

One frosty Sunday morn.The congregation stood about,

Coat-collars to the ears,

And talked of stock, and crops, and drought,

As it had done for years.“It’s looking crook,” said Daniel Croke;

“Bedad, it’s cruke, me lad,

For never since the banks went broke

Has seasons been so bad.”“It’s dry, all right,” said young O’Neil,

With which astute remark

He squatted down upon his heel

And chewed a piece of bark.And so around the chorus ran

“It’s keepin’ dry, no doubt.”

“We’ll all be rooned,” said Hanrahan,

“Before the year is out.”“The crops are done; ye’ll have your work

To save one bag of grain;

From here way out to Back-o’-Bourke

They’re singin’ out for rain.“They’re singin’ out for rain,” he said,

“And all the tanks are dry.”

The congregation scratched its head,

And gazed around the sky.“There won’t be grass, in any case,

Enough to feed an ass;

There’s not a blade on Casey’s place

As I came down to Mass.”“If rain don’t come this month,” said Dan,

And cleared his throat to speak —

“We’ll all be rooned,” said Hanrahan,

“If rain don’t come this week.”A heavy silence seemed to steal

On all at this remark;

And each man squatted on his heel,

And chewed a piece of bark.“We want an inch of rain, we do,”

O’Neil observed at last;

But Croke “maintained” we wanted two

To put the danger past.“If we don’t get three inches, man,

Or four to break this drought,

We’ll all be rooned,” said Hanrahan,

“Before the year is out.”In God’s good time down came the rain;

And all the afternoon

On iron roof and window-pane

It drummed a homely tune.And through the night it pattered still,

And lightsome, gladsome elves

On dripping spout and window-sill

Kept talking to themselves.It pelted, pelted all day long,

A-singing at its work,

Till every heart took up the song

Way out to Back-o’-Bourke.And every creek a banker ran,

And dams filled overtop;

“We’ll all be rooned,” said Hanrahan,

“If this rain doesn’t stop.”And stop it did, in God’s good time;

And spring came in to fold

A mantle o’er the hills sublime

Of green and pink and gold.And days went by on dancing feet,

With harvest-hopes immense,

And laughing eyes beheld the wheat

Nid-nodding o’er the fence.And, oh, the smiles on every face,

As happy lad and lass

Through grass knee-deep on Casey’s place

Went riding down to Mass.While round the church in clothes genteel

Discoursed the men of mark,

And each man squatted on his heel,

And chewed his piece of bark.“There’ll be bush-fires for sure, me man,

There will, without a doubt;

We’ll all be rooned,” said Hanrahan,

“Before the year is out.”

Why is the US Fed lowering interest rates?

Continuing on from my previous wondering about how panic-driven and effective current US (monetary) policy is, I notice these two posts from Paul Krugman …

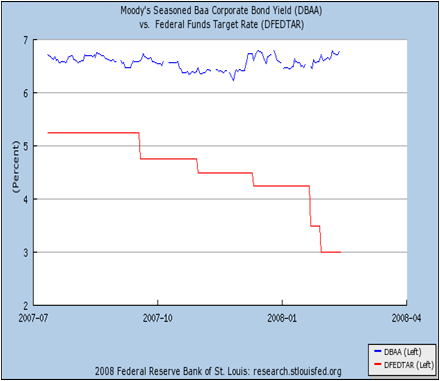

Ben Bernanke has cut interest rates a lot since last summer. But can he make a difference? Or is he just, as the old line has it, pushing on a string?

Here’s the Fed funds target rate (red line) — which is what the Fed actually controls — versus the interest rate on Baa corporate bonds (blue line), which is probably a better guide to what matters for actual business spending.

It’s pretty grim. Basically, deteriorating credit conditions have offset everything the Fed has done. Doubleplus ungood.

… and Brad DeLong …

Further cuts in the federal funds rate are on the way. Ben Bernanke is talking about how we are in a slow-moving financial crisis of DeLong Type II: one in which large financial institutions are insolvent–“pressure on bank balance sheets”–and in which lower short-term interest rates and a steeper yield curve are a way of providing institutions with the life jackets they need to paddle to shore.

Larry Meyers has pointed out that the BBB yield is no lower than it was in July–that all the easing has had no effect on the cost of capital that the financial markets feed to the “real economy,” and hence that Fed policy today is no more stimulative than it was last summer.

I’m more inclined to agree with Brad’s assessment than Paul’s implicit prediction of gloom, although it depends on what you think the Fed should be looking at. Paul is clearly hoping for a decrease in long-term rates so-as to stimulate the real economy, while Brad is simply noting that steeper yield curves, manifested here through a drop in base rates and no movement in longer-term paper, are pumping up banks’ profit flows, which will help them deal with the hideous losses from the sub-prime mess, the monoline insurer implosion and all the other nasties out there.

This seems like pretty clear “Bernanke put” behaviour to me. The banks need the short-term increase in profit flows in order to stay solvent in the medium-term. Whether Mr Bernanke is pushing down the base rate because the banks can’t lift the yields on long-term debt or because he doesn’t want them to (since that would hit the real economy) is a moot point.

This doesn’t change the fact that Bernanke is slopping out the good times to save the industry from its own mistakes. It’s probably safe to say that there’ll be no more knuckles rapped (except maybe those of the ratings agencies), so the real question is whether they’ll be allowed to make the same mistakes again …

Are US policy-makers panicking?

With respect to fiscal policy, I suspect that the stimulus package will help, but believe – like every other political cynic – that the package is being undertaken principally so that candidates in this year’s congressional, senate and presidential elections can be seen to be acting. I am not at all surprised that debate over the precise structure of the package never really rose above the blogosphere, since although that is of enormous significance in how effective it will be, it is of near utter insignificance from the point of view of being seen to act. I find myself agreeing both with Paul Krugman, who points out that only a third of the money will go to people likely to be liquidity-constrained and with Megan McArdle, who (here, here, here, here and here) argues that if you’re going to give aid to the poor of America, doing it via food stamps is, to say the least, less than ideal.

On the topic of monetary policy, I will prefix my thoughts with the following four points:

- The decision makers at the US Federal Reserve are almost certainly smarter than I am (or, indeed, my audience is)

- They certainly have more experience than I do

- They certainly put more effort into thinking about this stuff than I do

- They certainly have access to more timely and higher quality data than I do

As I see it, there are three different concerns: whether (and if so, how) monetary policy can help in this scenario; whether the Fed’s actions come with added risks; and whether the timing of the Fed’s actions were appropriate.

First up, we have concerns over whether monetary policy will have any positive effect at all. Paul Krugman (U. Princeton) worries:

Here’s what normally happens in a recession: the Fed cuts rates, housing demand picks up, and the economy recovers. But this time the source of the economy’s problems is a bursting housing bubble. Home prices are still way out of line with fundamentals … how much can the Fed really do to help the economy?

By way of arguing for a a fiscal package, Robert Reich (U.C. Berkley) has a related concern:

[A] Fed rate cut won’t stimulate the economy. That’s because lending institutions, fearing their portfolios are far riskier than they assumed several months ago, won’t lend lots more just because the Fed lowers interest rates. Average consumers are already so deep in debt — record levels of mortgage debt, bank debt, and credit-card debt — they can’t borrow much more, anyway.

Menzie Chinn (U. Wisconsin) looks at these and other worries by going back to the textbook channels through which monetary policy works, concluding:

In answer to the question of which sector can fulfill the role previously filled by housing, I would say the only candidate is net exports. The decline in the Fed Funds rate has led to a depreciation of the dollar. In the future, net exports will be higher than they otherwise would be. However, the behavior of net exports, unlike other components of aggregate demand, depends substantially on what happens in other economies. If policy rates decline in the UK, the euro area, and elsewhere, additional declines of the dollar might not occur. (And as I’ve pointed out before, if rest-of-world GDP growth declines (as seems likely [2]), then net exports might decline even with a weakened dollar).

I think the main point is that the decreases in interest rates, working through the traditional channels, will have a positive impact on components of aggregate demand. With respect to the credit view channels, the impact on lending is going to be quite muted, I think, given the supply of credit is likely to be limited. In fact, I suspect monetary policy will only be mitigating the negative effects of slowing growth and a reduction of perceived asset values working their way through the system.

James Hamilton (U.C. San Diego) is more sanguine, arguing that:

[I]t is hard to imagine that the latest actions by the Fed would fail to have a stimulatory effect.

[A]lthough interest rates respond immediately to the anticipation of any change from the Fed, it takes a considerable amount of time for this to show up in something like new home sales, due to the substantial time lags involved for most people’s home-purchasing decisions … According to the historical correlations, we would expect the biggest effects of the January interest rate cuts to show up in home sales this April.

[The scale of any effect is unknown, though.] Tightening lending standards rather than the interest rate have in my opinion been the biggest explanation for why home sales continued to deteriorate after January 2007 … The effect of rising unemployment and expectations of falling house prices on housing demand is another big and potentially very important unknown.

Going further, Martin Wolf at the FT worries that the Fed may be doing too much, that they the recent cuts in interest rates may serve only to renew or exacerbate the problems that caused the current crisis in the first place.

[P]essimists argue that the combination of declining asset prices (particularly house prices) with household overindebtedness and a fragile banking system means that monetary policy is, in the celebrated words of John Maynard Keynes, like “pushing on a string”. It may not be quite that bad. But, on its own, monetary policy will not act swiftly unless employed on a dramatic scale. The case for fiscal action looks strong.

Yet, in current US circumstances, monetary loosening should have some expansionary effects: it will encourage refinancing of home mortgages; it will weaken the exchange rate, thereby improving net exports; it will, above all, strengthen the health of banking institutions, by giving them cheap government loans.

This brings us to the biggest question: what are the risks? Unfortunately, they are large. One is indefinite continuation of an excessively low rate of US national saving. Others are a loss of confidence in the US currency and much higher inflation.Yet another is a further round of the very asset bubbles and credit expansion that created the present crisis. After all, the financial fragility used to justify current Fed actions is, in large part, the direct result of past Fed efforts at the risk management Mr Mishkin extols.

Moreover, the risks are not just domestic. If the US authorities succeed in reigniting domestic demand, this is likely to reverse the decline in the current account deficit. It will surely reduce the pressure on other countries to change the exchange rate, fiscal, monetary and structural policies that have forced the US to absorb most of the rest of the world’s huge surplus savings.

…

I find it impossible to look at what the US is now trying to do without feeling severely torn. If it succeeds it will renew and, at worst, exacerbate the fragility, both domestic and international, that triggered the turmoil. If it fails, the US and, perhaps, much of the rest of the world could well suffer a prolonged period of economic weakness. This is hardly a pleasant choice. But that it is indeed the choice shows how weakened the world economy and particularly the financial system has become.

In reaction at the FT’s hosted blog, Christopher Carroll (Johns Hopkins U.) argues:

This situation provides a more than sufficient rationale for the Fed’s dramatic actions: Deflation combined with a debt crisis make a toxic combination, because as prices fall, real debt rises. This point was amply illustrated in Japan, where deflation amplified both the number of zombies and the degree of zombification (among the initial stock of the undead). It was also the basis of Irving Fisher’s theory of what made the Great Depression great, and has clear echoes in the macroeconomic literature on the “financial accelerator” pioneered by none other than Ben Bernanke (along with a few other authors who have pursued more respectable careers).

In this context, the risk of an extra year or two of an extra point or two of inflation (if the deflation jitters prove unwarranted and the subprime crisis proves transitory) seems a gamble well worth taking.

Martin Wolf then replied:

[W]hat the Bernanke Fed seems to be trying to halt (with enthusiastic assistance from Congress and the president) is a natural and necessary adjustment, as Ricardo Hausmann argued in the FT on January 31st. I agree that this adjustment must not be too brutal. I agree, too, that both a steep recession and deflation should be avoided. I agree, finally, that market adjustments must not be frozen, as happened in Japan. But I disagree that the US confronts a huge threat of deflation from which the Fed must rescue the economy at all costs. What I fear it is doing, instead, is bailing out the banking system and so trying to reignite the credit cycle, with the consequent dangers of a flight from the dollar, considerably higher inflation and much more bad lending ahead.

Which leaves us with the third concern, over the timing of the rate cuts. The first of them, of 75 basis points, was the largest single cut in a quarter century. The fact that it came from an out-of-schedule meeting makes it almost unprecedented. When we add the fact that the world was in the middle of a broad share sell-off – exacerbated, it turns out, by the winding out of US$75 billion of bets by Societe General – it definitely has the appearance of a panicked decision. Adding the 50bp cut eight days later made for an enormous 1.25 percentage point drop in rates in a fraction over a week.

So what’s my take? Well …

1) The Fed is not as independent as central banks in other countries are. Greg Mankiw may not like it, but the fact is that both Congress and the Whitehouse actively seek to influence monetary policy in the United States. This photograph of Ben Bernanke (chairman of the US Federal Reserve), Christopher Dodd (chairman of the US senate’s banking committee) and Hank Paulson (US Treasury secretary) from mid-August 2007 is typical:

As Martin Wolf noted at the time:

This showed Mr Bernanke as a performer in a political circus. Mr Dodd even announced Mr Bernanke’s policies: the latter had, said Mr Dodd, told him he would use “all the tools ” at his disposal to contain market turmoil and prevent it from damaging the economy. The Fed has its orders: save Main Street and rescue Wall Street. Such panic-driven politicisation is almost certain to lead to both overreaction and the creation of bad precedents.

2) The Fed is mandated to keep both inflation and unemployment low. By comparison, the other major central banks are only required to focus on inflation. When they do look at unemployment, it plays lexicographic second fiddle to keeping inflation in check. At the Fed, they are compelled to take unemployment into account at the same time as looking at inflation.

3) The banking and finance system is central to the real economy. Without a ready supply of credit to worthy and profitable ventures, economic growth would slow dramatically, if not cease altogether. Although it creates a clear moral hazard when bankers’ pay is not aligned with real economic outcomes, this – combined with the first two points – implies that the so-called “Bernanke put” is probably, to some extent, real.

4) The latest GDP numbers and IMF forecasts were released in between the two rate cuts. I have nothing to back this up, but I wouldn’t be the least bit surprised to discover that the Fed gets (or got) a preview of those numbers. Seeing that markets were already tanking, knowing that the reports would send them tumbling further, perhaps believing that they might already be in a recession, almost certainly fearing that the negative news, if released before the Fed had acted, might send risk premia skywards again and recognising that what they needed was a massive cut of at least 100bp, perhaps the Fed concluded that the best policy was to split the cut over two meeting, making a smaller but still unusually large cut before the reports were released to ensure that they didn’t trigger more credit-crunchiness and a second one after in notional “response.”

My point is this: Which would seem more like a panicked response? The way that things did pan out, or a global stock market melt-down that took several more days to settle, followed by the markets being hit with surprisingly negative reports from the IMF on the global economy and the BEA on the US economy, and then a 125 b.p. drop in a single sitting by the Fed?