Brief answers to three questions about elections in the United Kingdom:

- Why do electoral boundaries favour Labour?

- Why would moving to Proportional Representation favour the Liberal Democrats?

- Why would moving to Alternative Vote/Instant Runoff/Preferential Voting favour the Liberal Democrats?

Why the current seat allocation is biased towards Labour

Two reasons:

Firstly, it’s because of demographics, migration and the timing of boundary changes. There’s a long-term trend across most of the country (excluding London) for people to be moving away from inner city areas and towards suburban, semi-rural and rural areas. On average, that represents a movement of Labour-party supporters into Conservative seats. As a result, the inner city areas remain staunchly pro-Labour, but the suburban and semi-rural areas become contested. Under British law, electoral boundaries are only updated very rarely. Quoting ukpollingreport.co.uk:

Because the effect of boundary changes is one way, any delay in keeping the boundaries up to date with population movements tends to be to the advantage of the Labour party and the disadvantage of the Conservatives.Currently, Parliamentary boundary reviews are based on the electorates at the time the boundary review commences (unlike local authorities boundaries, which are based on projections of the future electorate). In the case of the boundaries which will be used for the next election, the review began in 2000, so by the time the boundaries are first used in 2009/10 they will already be a decade out of date. By the time they are replaced by the next boundary review, due to report between 2014 and 2018, they will be close to 20 years out of date.

Secondly, there are different rates of turnout across different seats. The poor and poorly educated correlate positively with Labour support and negatively with turning out to vote.

To appreciate what this means, suppose that you had two seats with equal numbers of people living in them (contrary to the demographics mentioned above); one generally pro-Labour and the other generally pro-Tory. Let’s say that they each win 60-40. On election day only 25% of eligible voters turn up in the pro-Labour seat, but 75% of eligible voters turn up in the pro-Conservative seat. That will produce one Labour MP and one Tory MP (50% each), but when combined, the Conservatives will have received 60%*75% + 40%*25% = 55% of all the votes cast.

When combined with the demographic changes, this adds up to a significant advantage for Labour. Obviously the second distortion (but not the demographic one) vanishes if you introduce compulsory voting like we have in Australia.

How Proportional Representation would help the Lib Dems

This one is easy to explain:

- In 1992, the Lib Dems received 17.8% of the total vote, but only 3.1% of the seats in parliament.

- In 1997, the Lib Dems received 16.8% of the total vote, but only 7.0% of the seats in parliament.

- In 2001, the Lib Dems received 18.3% of the total vote, but only 7.9% of the seats in parliament.

- In 2005, the Lib Dems received 22.6% of the total vote, but only 9.5% of the seats in parliament.

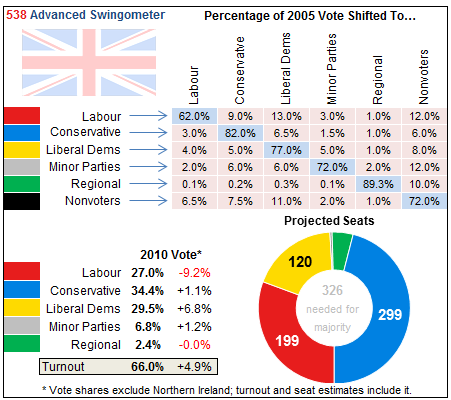

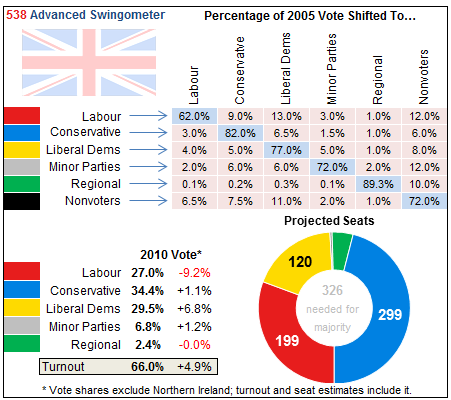

- According to the fivethirtyeight.com forecast, this week the Lib Dems will receive 28.7% of the total vote, but only 18.4% of the seats in parliament

How Alternative Vote/Instant Runoff/Preferential Voting would help the Lib Dems

Two reasons:

Firstly, with first-past-the-post, Lib Dem supporters have an incentive to vote for someone else so that their vote “counts”. This effect is particularly strong in contests that are perceived to be close (so it’s less of a concern this time).

Secondly, the Lib Dems do well when you ask people to rank their preferences – they’re rarely 1st, but they’re frequently 2nd. To really understand how this would affect things, have a look at the transition matrix fivethirtyeight.com uses in their prediction. This is their matrix for how they believe people have changed relative to 2005 (e.g. of previous Labour voters, 62% remain with Labour, 9% have switched to the Tories, 13% to the Lib Dems, etc):

It is therefore not really a matrix of average preferences, but it gives an idea of what it might be.

It is therefore not really a matrix of average preferences, but it gives an idea of what it might be.

When Labour supporters switch, they favour the Lib Dems over the Tories 13/9 = 1.44

When Tory supporters switch, they favour the Lib Dems over Labour 6.5/3 = 2.17

When Lib Dem supporters switch, they narrowly favour the Tories over Labour 5/4 = 1.25

So, with preferential voting and pretending that there are only the three parties contesting each seat:

If a Lib Dem candidate is in the top two after the first round of voting, they can be confident of receiving the majority of the preferences of the supporters of the 3rd ranked candidate, no matter who they were.

But that can’t be said for the other two parties. If a Labour or Tory candidate is in the twop two after the first round, whether they get a majority of the 3rd-place candidate’s preferences crucially depends on the identity of that 3rd-place candidate. If it was Lib Dem in 3rd place, it’s a flip of the dice. If it was the other big party in 3rd place, they’ll typically get only a minority of the preferences.

On average — over many seats and over several elections — that skewing of preference ranking will act in the Lib Dems’ favour with preferential voting.

Alternative Vote/Instant Runoff/Preferential Voting would help the Lib Dems