Something like 11 years ago, my brother got a dog. She was a border collie – blue australian cattle dog cross (the two most energetic breeds that exist) and, because my brother has always had a knack for naming things, he called her “Doris, the dog.”

A few years ago my brother bought his own place in town and so moved out of the cottage in which he’d lived at Mum and Dad’s place. Doris had always been a country dog and wouldn’t have done well in a small back yard, so he didn’t take her in with him (the cat, named “Cat,” did go). Instead, Doris stayed out with Mum and Dad and my brother would come out to play with her while telling our parents that of course he was there to see them.

Doris was, in many ways, an insane dog. When my parents moved to The Hill seven years ago, she was introduced, most painfully, to the local jumping cactus (more properly called Tiger pear, or scientifically, Opuntia aurantiaca).

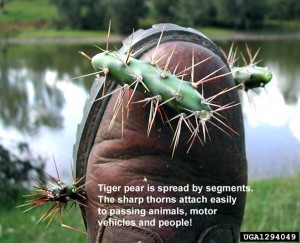

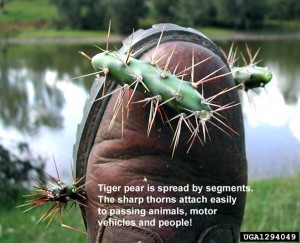

A quick aside. Jumping cactus is a vicious little bugger, because the segments are quite small (often just a centimetre or two) and the spines are fantastically long (two to three centimetres). The spines are barbed and the plant segments attached to each other by the loosest of connections, so the faintest possible touch will lead to one of them sticking in your trousers, shoes, foot or what have you. The barb on the spines (like a fish hook) means that they will not come out simply when pulled, but need to be ripped out in a manner that, if it’s your foot it’s emerging from, will bring tears to your eyes. Here’s a picture of the stuff attached to somebody’s boot:

Tiger pear is native to South America and was stupidly brought to Australia in the 1800s as an “ornamental garden plant.” It is now all over south-east Queensland and north-east New South Wales to the west of the Great Dividing Range and threatens to move over most of south-east Australia.

[The map comes from weeds.com.au]

Anyway. When my parents first moved to The Hill, poor Doris managed to step on some of the ghastly stuff and somebody — I don’t remember who; probably Mum — had the joy of holding her down and tearing the spines out of her foot with a pair of pliers. Doris was always a smart dog and didn’t blame the humans for this pain. She knew what was responsible and she must have vowed, in her little doggie brain, to take action.

From that day on, at every opportunity, she would pad around the top of the hill looking for jumping cactus and, upon discovering a patch, would settle down and eat them. I should stress that this ought to be utterly impossible. The spines, as mentioned earlier, are at least an inch long. There is no way that Doris could have eaten them without sticking herself in the mouth with an awful collection of fish-hooked spines. But she did it. Somehow, she did it, and she did it every time my mother went to work in the garden. Which is a lot. A lot.

She also believed firmly in attacking snakes, for exactly the same reason. Doris was bitten by snakes on, I think, three occasions on The Hill. She should have died from all three of them. She certainly should have died from the one that caused the skin on her stomach to die and rot away, leaving her innards exposed to the air. My parents are not heartless; they took her in to the vet, but the nice lady explained that full treatment would cost thousands of dollars and my parents are not made of money and, besides, they both grew up on and now, again, lived themselves on a farm. Things sometimes die on a farm. So they took Doris home with the hole in her stomach and were especially nice to her. Doris survived. Doris just kept the wound clean by licking it around the clock and it gradually grew over. In the end, you couldn’t see any scars and her hair grew back over the whole area. She got her own back, mind you. Every summer when the snakes came out, she wouldn’t back away, but would attack them; and I do mean attack. She’d grab and toss them, shaking her head to try to crack a spine or some such. Mum and Dad used to discover dead snakes on the front lawn, left as presents.

The point, as you might imagine, is that Doris was an absurdly tough dog. This is not particularly unusual for Australian Cattle Dogs. You should hear some of the stories about my uncle’s dog, a red aussie, called — well, what did you expect? — “Red.” But this isn’t a post about Red. It’s about Doris.

Doris loved to please. It was in her nature. The instinct of both the Cattle Dog and the Border Collie is to run, to chase, to track and to herd. For both, the link to their humans is near absolute. Doris was never trained as a proper cattle dog (much to her frustration when my parents started breeding a few cattle), but she loved chasing balls. She really loved chasing balls. When she got tired from the chasing, she loved taking the ball into the shade and chewing it to pieces. No doubt it was to keep her in shape for the next round of jumping cactus destruction. Occasionally my mother would buy one of those expensive, “indestructible” balls for her. I think the longest one of them lasted was 48 hours. No, the only way to preserve a ball was to stick it in a bag out of her reach.

Doris wasn’t utterly indestructible, mind you. Possibly because of some inherited condition, or possibly because of the string of snake bites, she suffered from a kind of arthritis. She’d be stiff getting up in the morning and she might take a little while to warm up. But once she was going, there was nothing stopping her.

Oh, the craziness. I forgot the craziness. Doris never quite understood storms. I don’t just mean that she was scared of thunder. Lots of dogs are scared of thunder. Doris thought that the thunder and lightning were some enormous, angry animal. Her fight-or-flight mode was often a random switch between the two. Sometimes she would run around the yard trying to bite the lightning in the distance; sometimes she would rip open the screen door and slink inside to hide in the kitchen. The first of these was just a source of laughter for Mum and Dad until Mum discovered that the same logic she’d applied to jumping cactus and snakes also applied to electricity. For some reason a wire had become exposed close to Doris’ kennel and was crackling a little. Doris tried to bite it. Fortunately, that didn’t kill her either. Tough.

Anyway, Daniela and I were back visiting over Christmas. My mum’s brother and his family came in from Roma the day after Boxing Day and we all played some backyard cricket. Doris, naturally, represented two-thirds of the fielding team. I was on The Hill for a good two weeks out of my three in Australia and I threw the ball for Doris every day. She’s a great dog. She was a great dog. This morning I woke up to this email from Mum:

A sad day. Doris died this morning. It is Australia Day so a holiday. I was mowing the lawn early and she was fine; chasing the mower trying to bite the wheel – she got it too! – I threw the ball for her a few times as I mowed. Your Dad and I were having coffee on the verandah at about 9am and she was lying on her mat under the family room window where she always lies, when I looked at her and she looked funny. Eyes open but not there. And that was it I guess the heart just stopped. No struggle, no noise, didn’t look distressed, just gone. We waited for an hour or so, I kept thinking she might not really have died but be having a fit as she sometimes does and then rang James. He was lovely and came out and helped bury her down under a big old ironbark tree overlooking the road.

On the upside, she didn’t appear to suffer at all. If I could eat chops the night before, chase a lawn mower an hour earlier and then lie down in the sun on the verandah surrounded by loved ones before I die – that would be about as good a way to go as any.

James stayed for the rest of the day and we’re all fine, just sad. She was 11 years old and such a good dog for out here. I keep thinking I can hear her outside. We’ll miss her for a long time.

Which is just about the most awful news I could possibly have received today. Doris was never my dog. I lived in the UK for seven of her eleven years and in Brisbane (two or three hours away) for the rest of them. But I’m going to miss her enormously. Rudyard Kipling wrote about this, many years ago. He was one of my grandmother’s favourite authors, and my mother’s too.

The Power Of The Dog

Rudyard Kipling

There is sorrow enough in the natural way

From men and women to fill our day;

And when we are certain of sorrow in store,

Why do we always arrange for more?

Brothers and Sisters, I bid you beware

Of giving your heart to a dog to tear.

Buy a pup and your money will buy

Love unflinching that cannot lie–

Perfect passion and worship fed

By a kick in the ribs or a pat on the head.

Nevertheless it is hardly fair

To risk your heart for a dog to tear.

When the fourteen years which Nature permits

Are closing in asthma, or tumour, or fits,

And the vet’s unspoken prescription runs

To lethal chambers or loaded guns,

Then you will find–it’s your own affair–

But…you’ve given your heart for a dog to tear.

When the body that lived at your single will,

With its whimper of welcome, is stilled (how still!);

When the spirit that answered your every mood

Is gone–wherever it goes–for good,

You will discover how much you care,

And will give your heart for the dog to tear.

We’ve sorrow enough in the natural way,

When it comes to burying Christian clay.

Our loves are not given, but only lent,

At compound interest of cent per cent.

Though it is not always the case, I believe,

That the longer we’ve kept ’em, the more do we grieve:

For, when debts are payable, right or wrong,

A short-time loan is as bad as a long–

So why in Heaven (before we are there)

Should we give our hearts to a dog to tear?

So long, Doris. It won’t be the same without you.