I’m no Andrew Leigh or Andrew Norton when it comes to thinking about education and the economics thereof, but what the hell … I wrote the following back in 2005 for some reason and thought it worth sharing:

I see some confusion about the differences between ‘educated’ and ‘skilled’ that I think many people are unappreciative of, unaware of, or quite deliberately gloss over. In part, I guess, it’s affected by the hodgepodge of meanings attached to the word ‘education’ itself. It’s certainly the acquisition of something, but is it ‘skills’, or is it ‘An Education’ (capitalisation deliberate)?

“An Education” is what some people might refer to as intellectual spinach – it’s good for you, eat it! – and is the logical extension of what the US calls Social Studies. It’s a look at history, the make-up of your society, your government, the philosophies that underpin it and so forth. It is, in essence, what used to be regarded as essential in the British upper-middle classes for spitting out a ‘gentleman’ and could perhaps be summarised as “the world and your place in it”.

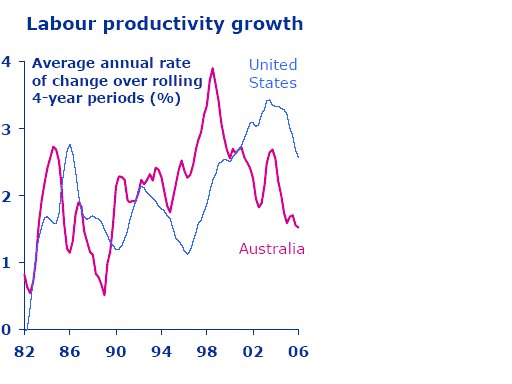

Skills, on the other hand, are what make you productive and therefore, valuable, to the economy. Skills are what businesses want and to a certain extent, all they’re interested in from their workforce.

The confusion comes about because, by simple virtue of our humanity, technology progresses. The things we do continually require less effort – fewer inputs, less physical work – to produce the same output. As such, the history and future of mankind as economic agents is entirely about a progression away from the physical and towards the intellectual and with that moves the skill-requirements of industry. This has made the acquisition of skills and the acquisition of “An Education” overlap. To excel in either now requires critical reasoning and imagination.

This hasn’t escaped the politicians of the world and when they speak of a skilled workforce being needed to take the economy forward, they’re talking about intellectual skills. They see universities as factories for producing skilled workers and this grates with those in academia who see universities as secular temples – places where supplicants go to seek enlightenment.

As society has progressed and the intellectual demands of the economy have grown, we’ve seen a corresponding increase in the number of years that a person spends in schooling before entering the workforce. I don’t doubt in the slightest that when people complain that two or three extra years is just blocking a person from being productive was made with the same force back when the push first came for most people to finish grade 12 at school rather than stopping at 10. Whatever the extension, the gist of it is to emphasise the intellectual development for longer and postpone the skills training until afterwards. The latest suggestion is just to hold off on the “skills” for a masters and to work on your critical reasoning through your undergrad.

This sounds fine in theory (we live longer and we earn more in real terms, so the cost of delaying our entry to the work force pays off), but it faces an ultimate dilemma in my opinion, and not just that we’re running out of academic levels to force kids through. The years of schooling that we force on our young has now extended well past the time of their physical and, to a large extent, psychological maturing. A kid is no longer expected to buck against the unfairness of the world while welding something in a factory, but to do it at university. That’s fine so long as there’s development of some kind to be had – we’ve always tied education to development – but what about when the person is a physically, psychologically and emotionally mature adult?

The technological progress of the world is not just continuing, either – it’s accelerating. That means that the rate at which the insufficiently skilled lose their value is only going to increase and with it, the demand for mid-life education is going to grow.

Thus, to my mind, there should be an almost fundamental rethink on how we allocate the fraction of our lives in education. Instead of doing all of it in one long burst at the start of our lives, we should be doing a large part of it initially, while we physically and psychologically develop, but then spread the rest out over time as we need it. Make the start-of-life education first and foremost about surviving in society, then focus on essential, universal skills and the development of critical thinking before just touching, broadly, on your career of choice. Then work for a time before returning to study to focus and specialise.

In addition to not forcing people to stay as underling students past their maturity, this allows people to change career direction with reasonable ease and for those people who don’t find what they want at university to not be discriminated against for the rest of their lives because education is a process and not an event that they missed.

Essential skills are the things that we probably all groan about: Typing, computer-use intuition, communication skills, both written and verbal. The things, in essence, that make a productive (though boring and uninspired) office worker.

This also addresses part of the question of university funding. The argument for free education centres around the fact that students have never had a job and so can’t pay for it up-front. The argument for making them pay up-front anyway hinges on an efficient capital market that allows them to borrow against future earnings. [Note added in 2008: I was pretty clearly ignoring the idea that parents could afford to pay the lot for their kids] Continuing education as I’ve described it would only happen after a person has been working for some time and has had a chance to save, so the problem is moot: Make them pay.