The Economist’s Babbage (i.e. their Science and Technology section) has a great article on the possibility of electric cars being used as battery packs for the power grid at large. Here’s the idea:

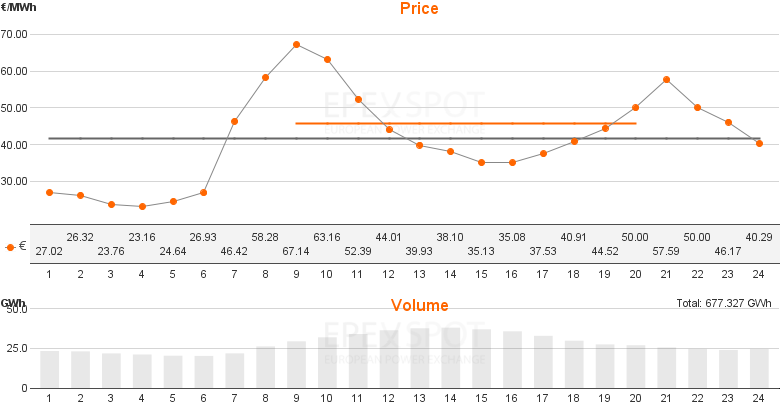

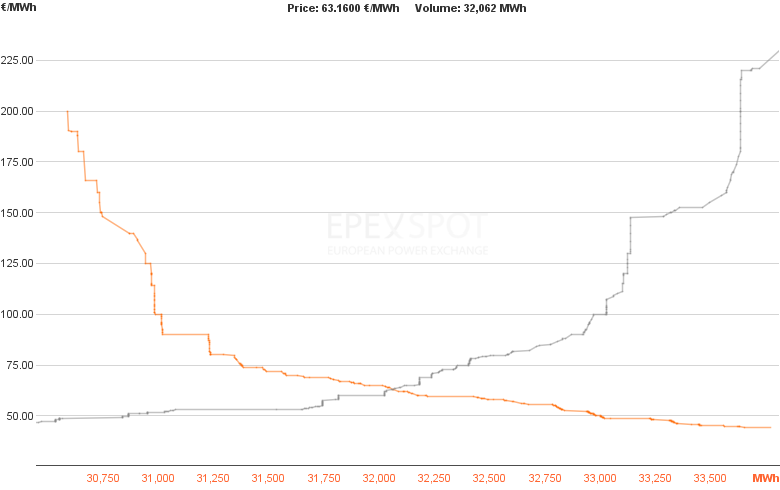

At present, in order to meet sudden surges in demand, power companies have to bring additional generators online at a moment’s notice, a procedure that is both expensive and inefficient. If there were enough electric vehicles around, though, a fair number would be bound to be plugged in and recharging at any given time. Why not rig this idle fleet so that, when demand for electricity spikes, they stop drawing current from the grid and instead start pumping it back?

Apparently it’s all called vehicle-to-grid (V2G). That (wikipedia) link has some great extra detail over the Economist piece. If you want more again, here is the research site of the University of Delaware on it. If you want more again (again), I’ve included links to the UK study by Ricardo and National Grid referenced in the Economist piece below.

After reading about the idea of V2G, a friend of mine asked a perfectly sensible question:

If having batteries connected up to the grid is a good thing for coping with spikes in demand, then why wouldn’t the power companies have dedicated batteries installed for this purpose?

I presume that power companies don’t install massive battery packs to obviate demand spikes because the cost of doing so exceeds the cost they currently incur to deal with them: having X% of their gross capacity sitting idle for most of the time.

In particular, the energy density of batteries isn’t great, and batteries do have a fairly low limit on the number of charge-discharge cycles they can go through.

In particular, the energy density of batteries isn’t great, and batteries do have a fairly low limit on the number of charge-discharge cycles they can go through.

Interestingly, another part of the cost associated with battery packs will be in the form of risk and uncertainty [*], which are exemplified by precisely this idea. If a power company were to purchase and install massive battery packs at the site of the generator only to see a tipping-point-style adoption of electric vehicles that, when plugged in, serve as batteries for hire situated at the site of consumption (i.e. can offer up power without transmission loss), they would have to book a huge loss against the batteries they just installed.

Technological innovation and adoption is disruptive and frequently cumulative, meaning that any market power created by it is likely to be short-lived, which in turn creates a short-run focus for companies that work in that space. For an infrastructure supplier more used to thinking about projects in terms of decades, that creates a strong status quo bias: by not acting now, they retain the option to act tomorrow once the new technologies settle down.

Anyway, I’m a huge fan of this idea. For a start, I’ve long been a huge fan of massively distributed power generation. Every household having an ability to sell juice back to the grid is just one example of this, but I think it should be something we could aim to scale both up and down. Imagine a world where anything with a battery could be used to transport and sell power back to the grid. My pie-in-the-sky dream is that I could partially pay for a coffee at my local cafe by letting them use some of my mobile phone’s juice for 0.00001% of their power needs for the day.

More realistically, the other big benefit of this sort of thing is that because the grid becomes better able to cope with demand spikes without being supplied by the uber generators, the benefit to the power company of maintaining that surplus capacity starts to fall. As a result, the balance would swing further towards renewable energy being economically (and not just environmentally) appealing.

At a first guess, I suspect that this also means that it is against the interests of existing power station owners for this sort of thing to come about, which ends up as another argument in favour of making sure that power generators and power distributors are separate companies. The distributor has a strong economic incentive to have a mobile supply that, on average, moves to where the demand is located (or better yet, moves to where the demand is going to be); the monolithic generator does not.

Back in December 2007 (i.e. when the financial crisis had started but not reached it’s Oh-God-We’re-All-Going-To-Die phase), Doctors Willett Kempton and Nathaniel Pearre reckoned a V2G car could produce an income of $4,000 a year for the owner (including an annual fee paid to them by the grid, about which I am highly sceptical). The Economist quite rightly points out that V2G, like so many things in life, would experience decreasing marginal value, but apparently it wouldn’t fall so far as to make it meaningless:

Of course, as the supply of electric vehicles increases, the value of each to the power company will fall. But even when such vehicles are commonplace, V2G should still be worthwhile from the car-owner’s point of view, according to a study carried out in Britain by Ricardo, an engineering firm, and National Grid, an electricity distributor. The report suggests that owners of electric vehicles in Britain could count on it to be worth as much as £600 ($970) a year in 2020, when an electric fleet 2m strong could provide 6% of the country’s grid-balancing capacity.

If you’re interested in the study by Ricardo and National Grid, the press release is here. That page also has a link to the actual report, but they want you to give them personal information before you get it. Thankfully, the magic of Google allows me to offer up a direct link to a PDF of the report.

The ever-sensible Economist also raises the upfront cost of capital installation by the distributor as something to keep in mind:

There is, it must be admitted, the issue of the additional cost of the equipment to manage all this electrical too-ing and fro-ing, not least the installation of charging points that can support current flows in both directions. But if the decision to make such points bi-directional were made now, when little of the infrastructure needed to sustain a fleet of electric vehicles has yet been built, the additional cost would not be great.

I can’t remember a damn thing from the “Electrical Engineering” part of my undergraduate degree [**], but despite the report from National Grid, I’m fairly sure that there would still be significant technical challenges (by which I mean real engineering problems) to overcome before rolling out a power grid with multitudes of mobile micro-suppliers, not to mention the logistical difficulties of tying your house, your car and your mobile phone battery to the same account and keeping track of how much they each give or take from any location, anywhere.

If I were a government wanting to directly subsidise targeted research to combat climate change I’d be calling in the deans of Electrical Engineering departments and heads of power distribution companies for a coffee and a chat. I’d casually mention some numbers that would make make them salivate a little and then I’d talk about open access and the extent to which patents are ideal in stimulating innovation. [***]

[*] By which I mean known unknowns and unknown unknowns respectively.

[**] Heck, I can’t remember a damn thing from the “Electronic Engineering” or the “Computing Engineering” parts, either.

[***] But that’s a topic for another post.