For those people that don’t know: A few days ago John Browlee discovered and wrote about an iPhone/iPad app called ‘Girls Around Me‘. The app does a mash-up of publicly accessible data from Facebook and foursquare, together with Google Maps, to show you girls that had checked in to locations near where you are and some information about them. John was not amused:

[T]he girls (and men!) shown in Girls Around Me all had the power to opt out of this information being visible to strangers, but whether out of ignorance, apathy or laziness, they had all neglected to do so. This was all public information. […]

“It’s not, really, that we’re all horrified by what this app does, is it?” I asked, finishing my drink. “It’s that we’re all horrified by how exposed these girls are, and how exposed services like Facebook and Foursquare let them be without their knowledge.” […]

This is an app you should download to teach the people you care about that privacy issues are real, that social networks like Facebook and Foursquare expose you and the ones you love, and that if you do not know exactly how much you are sharing, you are as easily preyed upon as if you were naked.

Picking up on John’s piece, Charlie Stross took the ball and ran with it, extrapolating out into the truly horrific:

It’s easy to imagine how we could make something worse than “Girls Around Me”—something much worse. Facebook encourages us to disclose a wide range of information about ourselves, including our religion and a photograph. Religion is obvious: “Yids Among Us” would obviously be one of the go-to tools of choice for Neo-Nazis. As for skin colour, ethnicity identification from face images is out there already. Want to go queer bashing? There’s an algorithm out there for guessing sexual orientation based on the network graph of the target’s facebook friends. It’s probably possible to apply this sort of data mining exercise to determine whether a woman has had an abortion or is pro-choice.

In the worst case, it’s possible to envisage geolocation and data aggregation apps being designed to facilitate the identification and elimination of some ethnic or class enemy, not only by making it easy for users to track them down, but by making it easy for users to identify each other and form ad-hoc lynch mobs. (Hence my reference to the Rwandan Genocide earlier. Think it couldn’t happen? Look at Iran and imagine an app written for the Basij to make it easy to identify dissidents and form ad-hoc goon squads to proactively hunt them down. Or any other organization in the post-networked world that has a social role corresponding to the Red Guards.)

Not surprisingly, people freaked out. Foursquare pulled the app’s access rights to their data, Apple pulled the app from the iTunes store altogether and — no doubt to the great relief of people like John and Charlie — a lot of people started talking about internet privacy in an era of social networking (e.g. a BBC News article).

Both John and Charlie emphasise that their concern is not with the app itself, per se, but with the approach to privacy (public by default) built-in to social networking websites’ very business plans that allowed the app to exist in the first place.

I want to defend that approach to privacy.

Let me repeat the first bit of that John Brownlee quote:

[T]he girls (and men!) shown in Girls Around Me all had the power to opt out of this information being visible to strangers, but whether out of ignorance, apathy or laziness, they had all neglected to do so.

Here is Marie Connelly, one of the girls that John apparently had around him, in response to the whole kerfuffle:

I have a problem [with this], because I’m not ignorant, apathetic, or lazy.

I’ve made a choice to participate publicly in the internet. I try to be careful about what I make accessible and what I share with everyone, and for the most part, I think I’ve found a balance that works pretty well for me. […]

The whole tenor of this, however, has been that if you are in this app, if you have been posting information publicly, especially if you’re a woman, you’re doing something wrong. […]

Checking in at your office, or a coffee shop, or The Independent (which is a great bar, by the way), whether publicly or not, doesn’t mean you’re “asking” to get stalked, or mugged, or anything else. People generally don’t ask for bad things to happen to them, and by and large, I don’t really believe anyone deserves to have something bad happen to them.

Kashmire Hill captured the same point in her excellently titled post, “The Reaction To ‘Girls Around Me’ Was Far More Disturbing Than The ‘Creepy’ App Itself“:

- All men are creepy stalkers looking for new digital aids to help them catch and rape women.

- All women are damsels-in-distress who have no idea how much danger they are exposing themselves to with every Foursquare check-in.

- “You’re too public with your digital data, ladies,” may be the new “your skirt was too short and you had it coming.”

Those are my takeaways from the past week’s furor over “Girls Around Me.” […]

Many of us have become comfortable putting ourselves out there publicly in the hopes of making connections with friends and with strangers, whether through Facebook, Twitter, or OKCupid. It’s only natural that this digital openness will transfer over to the ‘real world,’ and that we will start proactively projecting our digital selves to facilitate in-person interactions. (For example, KLM is now allowing passengers to link their digital identities to their seats on the plane so that people can choose seatmates accordingly.) […]

In rejecting and banishing the app, we’re choosing to ignore the publicity choices these women have made … in the name of keeping them safe … If you extend this kind of thinking ‘offline,’ we would be calling on all women to wear burkas so potential rapists and stalkers don’t spot them on the streets and follow them home.

I’m sorry, my friends, but I think apps like ‘Girls Around Me’ are the future … We don’t fear making connections with strangers; we crave it. […]

Yes, think about your privacy settings. They’re important. But critics, also remember that some of us have thought about our privacy settings, chosen accordingly, and don’t mind showing up on geo-mapping apps. We’re not all damsels-in-distress going pale at the thought of being seen in public places and digital spaces.

I couldn’t possibly agree more.

I’m happy to require by law that all websites that gather personal information give plain-English explanations of how your information might be used under each setting. I’m also happy to be very, very angry at Facebook for changing their policy in such a way as to change your settings from “keep this private” to “make this public” after you made an explicit choice (although, to be fair, social networks are still a new industry and should consequently be granted at least some leeway for their frequent adjustments).

But there’s a much bigger topic here. Whether or not public exposure has negative consequences is a social norm, based on co-ordination effects. It’s socially acceptable in America for girls to wear bikinis at the beach, for girls in France to go topless at the beach and for people to use mixed-sex saunas and public showers throughout Germany and the Scandinavian countries. It’s not as though they have massive rates of rape or sexual abuse.

The reason I see no problem with apps like ‘Girls Around Me’ is because I believe they represent the emergence of a new social norm that supports and encourages the public sharing of information about yourself, perhaps even a step towards David Brin’s Transparent Society. Disagree with me? Well, I would argue that of those people that (a) are doing it; (b) don’t realise they’re doing it; and (c) would actually care if they were to discover they’re doing it, the vast majority are over the age of 30. In other words, this is a generational development.

Here’s an excellent example of that generational change. Earlier this year the NY Times wrote about teenagers’ new habit of sharing their passwords with their (boy|girl)friends:

Young couples have long signaled their devotion to each other by various means — the gift of a letterman jacket, or an exchange of class rings or ID bracelets. Best friends share locker combinations.

The digital era has given rise to a more intimate custom. It has become fashionable for young people to express their affection for each other by sharing their passwords to e-mail, Facebook and other accounts. Boyfriends and girlfriends sometimes even create identical passwords, and let each other read their private e-mails and texts. […]

In a 2011 telephone survey, the Pew Internet and American Life Project found that 30 percent of teenagers who were regularly online had shared a password with a friend, boyfriend or girlfriend. The survey, of 770 teenagers aged 12 to 17, found that girls were almost twice as likely as boys to share. And in more than two dozen interviews, parents, students and counselors said that the practice had become widespread.

Knowing their audience, though, they couldn’t help being a little worried about it (and, of course, nothing sells newspapers like sex):

Rosalind Wiseman, who studies how teenagers use technology and is author of “Queen Bees and Wannabes,” a book for parents about helping girls survive adolescence, said the sharing of passwords, and the pressure to do so, was somewhat similar to sex.

Sharing passwords, she noted, feels forbidden because it is generally discouraged by adults and involves vulnerability. And there is pressure in many teenage relationships to share passwords, just as there is to have sex. […]

Ms. Cole’s mother, Patti, 48, a child psychologist, said she believed her daughter would be more judicious now about sharing a password. But, more broadly, she thinks young people are sometimes drawn to such behavior as they might be toward sex, in part because parents and others warn them against doing so.

“What worries me is we haven’t done a very good job at stopping kids from having sex,” she said. “So I’m not real confident about how much we can change this behavior.”

Speaking of sex and intergenerational concerns, this whole affair reminds me enormously of a post I wrote back in 2008 about the increasing public acceptability of sex for it’s own sake:

These developments are not without their concerns. Sara Montague – a presenter on BBC Radio 4′s Today programme – is clearly concerned, noting that much of the movement seems grounded in the hope of empowerment and self-confidence, but worrying that this serves indirectly to promote eating disorders among girls and the acceptance of rape among boys.

The main problem that Montague faces is that for most people, embracing public sexuality is non-harmful – not every girl gets an eating disorder and not every boy contemplates forcing himself on a girl – and is undertaken by choice. Montague is, in essence, faced with Douglas Adams’ cow that wants to be eaten. […]

By all means work to increase support for those burdened excessively by concerns of body image. By all means increase support to rape victims and ease the ability of the state to bring those guilty to justice. But that doesn’t mean we should fight to stop it altogether if people choose it freely and feel that it helps them, or even if they just enjoy it.

Anyway, that brings me back to ‘Girls Around Me’. It — and other apps like it — really are designed to be fun, to let Kashmir and people like her make connections with strangers. Yes, of course Facebook and Foursquare can be used by creepy stalkers and Rwanda 2.0 ethnic cleansers. So what? I have a 20cm Global Cook knife beside me right now. I could use it to cut chunks out of hipsters, but that doesn’t make it flawed by design. My credit card can be used to fund the KKK, but it’s also useful for other stuff, too. There’s nothing wrong (and there should be nothing illegal) with having information. It’s only when somebody acts on information in a manner harmful to others that we should care. ‘Girls Around Me’ was about sharing information; how people act on that information is up to them.

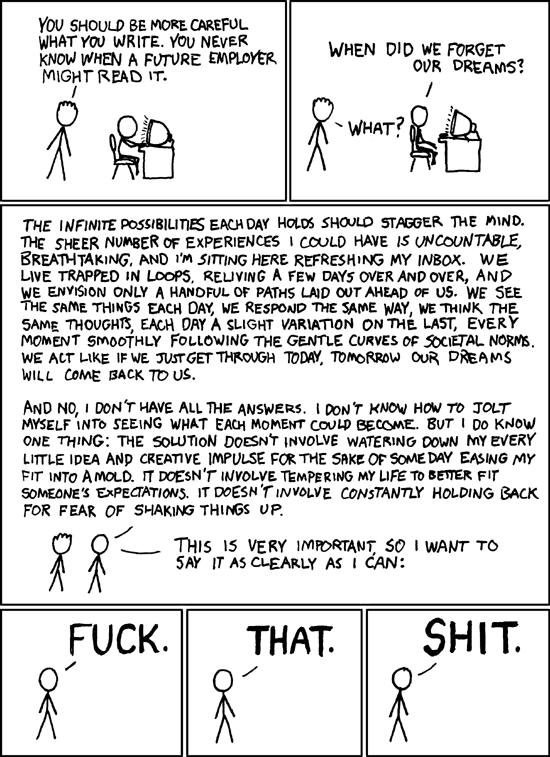

Let me finish with this incredibly relevant and, as ever, excellent comic from xkcd: