I am a chronic starter. It seems that every week or two I start something new. This would be great, if only I then kept doing whatever it is that I start.

One of the things that I start doing on a regular basis is running. Just about every year, usually about half-way through summer, I start running again. Every year I keep a careful log of what I do, every year I try not to build up too quickly, every year I become tremendously enthusiastic, every year I dream of completing the London Marathon and every year, without fail, I stop running after a month and a half.

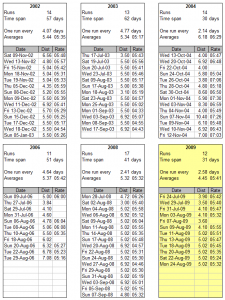

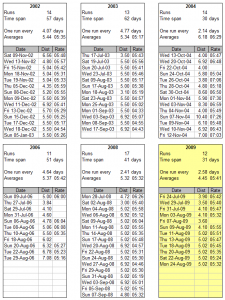

(Click on the image for a bigger version. Distances are in kilometres; rates are min/km)

I used to be a runner. Back in 1992, my final year of high school, I ran four times a week on top of two weekly sessions of soccer training in the winter and cricket in the summer. In the middle of that year I ran the Gold Coast Half-Marathon in 1:38:37 (4 min 40 sec per kilometre). Later that year I ran a cross-country 8km in 32 minutes flat. I was in the Queensland junior orienteering team.

I’ve always thought of myself as a runner (well, okay, a lapsed runner). I’ve blamed everything I could imagine for my repeated failure to get into a habit again. Diet. Running too far. Running too quickly. Not enough time to rest between runs. Too much time between runs. Not running on the same days of the week. Insufficient variety in my routes. Not running with music. Not running enough with other people.

I generally hold that with exercise (hell, with anything), what propels you forward is novelty in the short term, discipline in the medium term and habit in the long term. The trick, then, is to find a way to deal with a chronic lack of self-discipline in the medium term when you’ve ruled out options like joining the military to have discipline imposed upon you.

Here’s an email I sent to some of my friends last year (21 Aug 2008):

It’s not that I get bored with the runs when I’m on them – I tend to vary my courses and occasionally run with a club. As far as I can tell, I just get to a point where I can’t be arsed going today, tell myself I’ll go tomorrow, end up only going in three or four days and then repeat the process with the lags becoming longer until I just forget about it altogether. I have tended to get quite tired after the first couple of weeks, which suggests that an inappropriate diet might be the cause, but I’m hesitant to use that as the explanation when the phrase “I’m a lazy bastard” is swimming gently across my forebrain. There’s also the possibility that I rapidly envisage absurdly ambitious goals when I first start and manage to discourage myself before I’ve even built the habit of running.

So. I’m looking for suggestions on how to keep it going this time. I’ve managed nine runs so far and all pretty evenly spaced (see attached). The 5km runs are on the Heath, the 7km runs are with a running club of 80+ people around Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens. Runs on the Heath are infinitely variable. I don’t start back at uni for six weeks and have no work planned, so it’s a perfect opportunity to build up a weekly ritual.

My friend Chris replied (22 Aug 2008) with:

My most successful tactic: grinding down the barriers of participation.

The thing that makes it hard to run is NOT the running. It’s the transition from comfort and inertia to physical discomfort and effort (usually in the dark and cold in England). You have to look at what you need to achieve: in the first few months you are trying to achieve a HABIT. Nothing else. You’re not trying to achieve physical fitness, training, distance or anything else.

So looking at it as habit training, the best thing you can do is work on the habit above all else. It doesn’t matter a toad’s cloaca whether you go out and run 12k or 400 metres, if you stop a fortnight later. And as you know, stopping is never a decision to stop running. It’s a decision to take tonight off and go tomorrow instead. Then tomorrow. Then tomorrow…

The only way to succeed is to form the habit above all else, and the only workable way to form the habit is to make the habit easy. So, change your goal. It’s not to go for a run, it’s to put your tights on and step outside the door. Make THAT what you do 3 times/week (or better, every Tues, Thurs and Sunday, since “3/week” gives you wiggle room).

So 3 times a week you will put your shoes and silver bodysuit on, and walk to the gate. What happens then is purely a matter of how you’re feeling at the time. Until you are standing at the gate, you are not planning anything else.

Pound down the delta between what you are doing now (vegging in a warm lounge room) and what you will be doing in 10 minutes (standing outside your door). Smash the crap out of that delta, because that’s your only enemy.

Which is eminently sensible advice, but as you’ll see above in the image, I stopped running two weeks later. There was something missing.

Another friend, Anthony, also suggested last year that I

drop down a lot of cash on an event, such as Noosa Tri, which gives [you] some financial and pride incentives not to look like a fat unfit bastard on the day.

Again, excellent advice, but unless I have a basic belief that even with no training at all I can still cough and wheeze my way around the course, there’s a fair chance that if it’s all seeming a bit too hard I’ll just give up and call the cash gone. However, it does lead into the classic economist’s way of solving any problem: financial incentives. In January 2008, Ian Ayres, Jordan Goldberg and Dean Karlan (two of them economists) lauched stickK.com. It’s a site that will let you set up a contract on yourself (e.g. to lose weight). If you don’t meet the terms of the contract, you forfeit money.

I think it’s a neat idea, but it’s never really sat well with me. If your money is potentially going to a charity that you hate, then that’s just stupid. If it’s going to a charity that you like, then your incentives are all screwed up. So instead, I’ve decided on a different idea:

As soon as I finish writing this post, I’m going to go to the bank and withdraw £520. I will then divide it across eight envelopes and give them all to a good friend, Dimitri, with strict instructions to return the money back to me piecemeal as he is satisfied that I have gone for a run. The amounts returned will be increasing over time, so the first run will get me £30 back, the second £40 and so on up to the eighth run being worth £100. There will be a time limit of three weeks on my claiming the money back and a limit of no more than four runs being claimed per week. Here are the benefits, as I see them:

- Dimitri is a good friend and I trust him not to run off with my money.

- If I don’t meet the requirements, I also trust Dimitri to not turn Good Bloke and give me the money back anyway.

- He is pretty fit at the moment, having just competed in the London Triathlon, and is training regularly himself.

- It’ll be up to Dimitri to judge whether he believes me when I say I went for a run.

- The total amount of money is large enough that I will really want to get it back.

- The incentive is increasing over time, so I won’t be tempted to just go for a couple of runs and call it quits.

- The overall time limit combined with the restriction of no more than four runs per week will make sure that I don’t put it off and that I don’t end up hurting myself.

- Possibly most importantly of all, it extends the period of novelty well into the period that would otherwise be solely governed by (a lack of) discipline.

Eight more runs will take me to 20 in total. If it goes well and Dimitri is willing, I might then repeat the process. After that, I should hopefully have been running for long enough that I can get myself out the door without the financial incentive.