Apple just reported their profits for 2011Q4. It turns out that they made rather a lot of money. So much, in fact, that they blew past/crushed/smashed expectations as their profit more than doubled on the back of tremendous growth in sales of iPhones and iPads. [snark] I’ll bet nobody’s talking about Tim Cook being gay now. [/snark]

It’s an incredible result; stunning, really. I just wish it didn’t make me so depressed.

I salute the innovation and cheer on the profits. That is capitalism at its finest and we need more of it.

It’s that f***king mountain of cash (now up to $100 billion) that concerns me, because it’s symptomatic of what is holding America (and Britain) in the economic doldrums.

The return Apple will be getting on that cash will be miniscule, if it’s positive at all, and conceivably negative. Standing next to that, their return on assets excluding cash is phenomenal.

Why aren’t they doing something with the cash? Are they not able to expand profits still further by expanding quantities sold, even in new markets? Are there no new internal projects to fund? No competitors to buy out? Why not return it to shareholders via dividends or share buybacks?

Logically, a company holds cash for some combination of three reasons: (a) they use it to manage cash flow; (b) they can imagine buying an outside asset (a competitor or some other company that might complement them) in the near future and they want to be able to move quickly (and there’s no M&A deal that’s agreed upon faster than an all cash deal); or (c) they want to demonstrate a degree of security to offset any market perceived risk with their debt.

Apple long ago surpassed all of these benefits. The net marginal value of Apple holding an extra dollar of cash is negative because it returns nothing and incurs a lost opportunity cost. So why aren’t their shareholders screaming at them for wasting the opportunity?

The answer, so far as I can see, is because a significant majority of AAPL’s shareholders are idiots with a short-term focus. They have no goddamn clue where else the money should be and they’re just happy to see such a bright spot in their portfolio. Alternatively, maybe the shareholders aren’t complete idiots — Apple’s P/E ratio has been falling for a while now — but the fundamental point is that they have a mountain of cash that they’re not using.

In 2005 that wouldn’t have been as much of a problem because the shadow banking system was in full swing, doing the risk/liquidity/maturity transformation thing that the financial industry is meant to do and so getting that money out to the rest of the economy.[*] Now, the transformation channel is broken, or at least greatly impaired, and so nobody makes any use of Apple’s billions. They just sit there, useless as f***, while profitable SMEs can’t raise funds to expand and 15% of all Americans are on food stamps.

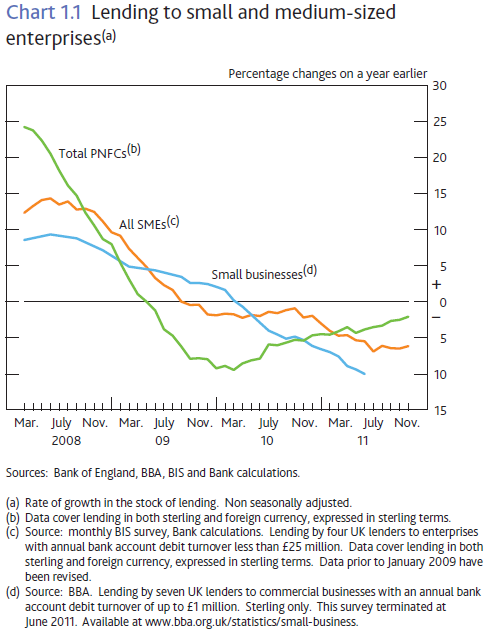

Don’t believe me? Here’s a graph from the Bank of England showing year-over-year changes in lending to small- and medium-sized enterprises in the UK. I can’t be bothered looking for the equivalent data for the USA, but you can rest assured it looks similar. The report it’s from can be found here (it was published only a few days ago). The Economist’s Free Exchange has some commentary on it here (summary: we’re still in trouble).

So what is happening to all that money? Well, Apple can’t exactly stick it in a bank account, so they repo it, which is a fancy way of saying that they lend it to a bank (or somebody else in the financial industry) and temporarily take some high quality asset like a US government bond to hold as collateral. They repo it because that’s all they can do now — there are no AAA-rated, actually safe, CDO tranches being created by the shadow banking system any more, they’re too big to make use the FDIC’s guarantee (that’s an excellent paper, btw … highly recommended) and so repo is all they have left.

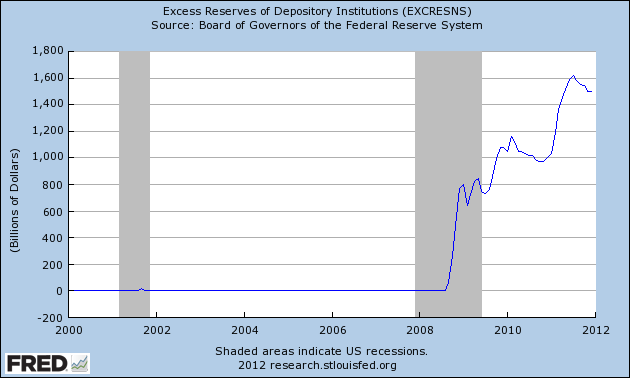

But the financial industry is stuck in a disgusting mess like some kid’s hair with chewing gum rubbed through it. They’re all just as scared as the next guy (especially of the Euro problems) and so they’re parking it in their own accounts at the Fed and the BoE. As a result, “excess” reserves remain at astronomical levels and the real economy makes no use of Apple’s billions.

That’s a tragedy.

[*] Yes, the shadow banking industry screwed up. They got caught up in real estate fever and sent (relatively) too much money towards property and too little towards more sustainable investments. They structured things in too opaque a manner, failed to have public price discovery and operated under distorted incentives. But they operated. Otherwise useless cash was transformed into real investment and real jobs. Unless that comes back, America and the UK will stay in their slow, painful household deleveraging cycle for another frickin’ decade.