… I promise!

New Scientist is loopy

New Scientist has a feature this week blaming the unsustainable destruction of the environment on an obsession with economic growth and calling for a move to a growth-free world. The answers to the questions raised by the collection of articles (all essentially repeating each other) are straightforward and widely recognised:

- As the supply of something dwindles or the demand for it rises, the price of that thing will rise. If we run low on some particular natural resource or our demand for it at the current price proves greater than the supply, the price will rise. That will cause demand to fall and will spur innovation in searching for an alternative. Trains in Britain first ran on coal-fired steam engines. Eventually the price of coal rose too high and they switched over to diesel. The price of oil was going up too, so after that they moved to electric engines. The transitions aren’t perfectly smooth, I’ll grant you – there are discrete jumps that can make it a bumpy ride – but it does happen.

- Externalities exist, both good and bad. Actions that come with positive externalities ought to be subsidised. Actions that come with negative externalities ought to be penalised. We’re producing too much carbon dioxide? Make the polluters pay. Whether it should be through taxes or a trading system is a matter of debate, but bring it in. We’re over-fishing in the North Atlantic? Impose a tax directly on the fishermen for every fish they catch. When the cost of doing a bad thing rises, people do it less and innovate to find an alternative.

- Yes, extreme inequality is a Bad Thing ™. It’s true that for some time we’ve had worsening inequality because of low growth among the poor and high growth among the rich, but that doesn’t mean that growth is bad per se, only that the composition of growth is around the wrong way. It is far better to have low growth for the rich and high growth for the poor (so they catch up) than to have no growth at all and rely entirely on redistribution. Redistribution should happen, yes, but primarily for the purposes of enabling the poor to grow faster. Have the rich pay for the health care and education of the poor.

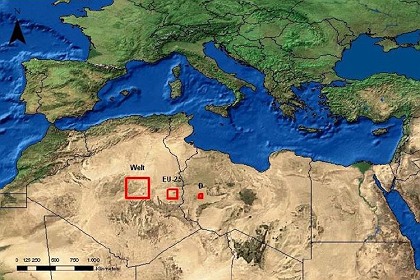

You don’t think this all this is possible? Of course it’s possible. Here is an article from Der Spiegel from April 2008 talking about solar power and the Sahara desert. Here is a map from that same article:

The caption reads: “The left square, labelled “world,” is around the size of Austria. If that area were covered in solar thermal power plants, it could produce enough electricity to meet world demand. The area in the center would be required to meet European demand. The one on the right corresponds to Germany’s energy demand.”

If the cost of coal- and gas-fired electricity production were high enough, this would happen so fast it would make an historian’s head spin.

That’s quite a jump

Following on from observing that Obama’s fundraising (and therefore advertising) success gives Republicans an excuse for losing the upcoming election, I see the following:

In August 2008, the Obama campaign set a record for the most successful fundraising month ever for a US presidential campaign: $66 million.

On the 29th of August 2008, John McCain presented Sarah Palin as his vice-presidential candidate.

In September 2008, the Obama campaign blows their August fundraising figure out of the water, this time managing over $150 million.

Power proportional to knowledge

Arnold Kling, speaking of the credit crisis and the bailout plans in America, writes:

What I call the “suits vs. geeks divide” is the discrepancy between knowledge and power. Knowledge today is increasingly dispersed. Power was already too concentrated in the private sector, with CEO’s not understanding their own businesses.

But the knowledge-power discrepancy in the private sector is nothing compared to what exists in the public sector. What do Congressmen understand about the budgets and laws that they are voting on? What do the regulators understand about the consequences of their rulings?

We got into this crisis because power was overly concentrated relative to knowledge. What has been going on for the past several months is more consolidation of power. This is bound to make things worse. Just as Nixon’s bureaucrats did not have the knowledge to go along with the power they took when they instituted wage and price controls, the Fed and the Treasury cannot possibly have knowledge that is proportional to the power they currently exercise in financial markets.

I often disagree with Arnold’s views, but I found myself nodding to this – it’s a fair concern. I’ve wondered before about democracy versus hierarchy and optimal power structures. I would note, however, that Arnold’s ideal of the distribution of power in proportion to knowledge seems both unlikely and, quite possibly, undesirable. If the aggregation of output is highly non-linear thanks to overlapping externalities, then a hierarchy of power may be desirable, provided at least that the structure still allows the (partial) aggregation of information.

Obama’s spending gives Republicans an excuse

So Barack Obama is easily outstripping John McCain both in fundraising and, therefore, in advertising. I’m hardly unique in supporting the source of Obama’s money – a multitude of small donations. It certainly has a more democratic flavour than exclusive fund-raising dinners at $20,000 per plate.

But if we want to look for a cloud behind all that silver lining, here it is: If Barack Obama wins the 2008 US presidential election, Republicans will be in a position to believe (and argue) that he won primarily because of his superior fundraising and not the superiority of his ideas. Even worse, they may be right, thanks to the presence of repetition-induced persuasion bias.

Peter DeMarzo, Dimitri Vayanos and Jeffrey Zwiebel had a paper published in the August 2003 edition of the Quarterly Journal of Economics titled “Persuasion Bias, Social Influence, and Unidimensional Opinions“. They describe persuasion bias like this:

[C]onsider an individual who reads an article in a newspaper with a well-known political slant. Under full rationality the individual should anticipate that the arguments presented in the article will reect the newspaper’s general political views. Moreover, the individual should have a prior assessment about how strong these arguments are likely to be. Upon reading the article, the individual should update his political beliefs in line with this assessment. In particular, the individual should be swayed toward the newspaper’s views if the arguments presented in the article are stronger than expected, and away from them if the arguments are weaker than expected. On average, however, reading the article should have no effect on the individual’s beliefs.

[This] seems in contrast with casual observation. It seems, in particular, that newspapers do sway readers toward their views, even when these views are publicly known. A natural explanation of this phenomenon, that we pursue in this paper, is that individuals fail to adjust properly for repetitions of information. In the example above, repetition occurs because the article reects the newspaper’s general political views, expressed also in previous articles. An individual who fails to adjust for this repetition (by not discounting appropriately the arguments presented in the article), would be predictably swayed toward the newspaper’s views, and the more so, the more articles he reads. We refer to the failure to adjust properly for information repetitions as persuasion bias, to highlight that this bias is related to persuasive activity.

More generally, the failure to adjust for repetitions can apply not only to information coming from one source over time, but also to information coming from multiple sources connected through a social network. Suppose, for example, that two individuals speak to one another about an issue after having both spoken to a common third party on the issue. Then, if the two conferring individuals do not account for the fact that their counterpart’s opinion is based on some of the same (third party) information as their own opinion, they will double-count the third party’s opinion.

…

Persuasion bias yields a direct explanation for a number of important phenomena. Consider, for example, the issue of airtime in political campaigns and court trials. A political debate without equal time for both sides, or a criminal trial in which the defense was given less time to present its case than the prosecution, would generally be considered biased and unfair. This seems at odds with a rational model. Indeed, listening to a political candidate should, in expectation, have no effect on a rational individual’s opinion, and thus, the candidate’s airtime should not matter. By contrast, under persuasion bias, the repetition of arguments made possible by more airtime can have an effect. Other phenomena that can be readily understood with persuasion bias are marketing, propaganda, and censorship. In all these cases, there seems to be a common notion that repeated exposures to an idea have a greater effect on the listener than a single exposure. More generally, persuasion bias can explain why individuals’ beliefs often seem to evolve in a predictable manner toward the standard, and publicly known, views of groups with which they interact (be they professional, social, political, or geographical groups)—a phenomenon considered indisputable and foundational by most sociologists[emphasis added]

While this is great for the Democrats in getting Obama to the White House, the charge that Obama won with money and not on his ideas will sting for any Democrat voter who believes they decided on the issues. Worse, though, is that by having the crutch of blaming the Obama campaign’s fundraising for their loss, the Republican party may not seriously think through why they lost on any deeper level. We need the Republicans to get out of the small-minded, socially conservative rut they’ve occupied for the last 12+ years.

Paul Krugman wins the Nobel (updated)

There is no doubt in my mind that Professor Krugman deserves this, but who doesn’t think that this is just a little bit of an “I told you so” from Sweden to the USA?

Update: Alex Tabarrok gives a simple summary of New Trade Theory. Do read Tyler Cowen for a summary of Paul Krugman’s work, his more esoteric writing and some analysis of the award itself.

I have to say I did not expect him to win until Bush left office, as I thought the Swedes wanted the resulting discussion to focus on Paul’s academic work rather than on issues of politics. So I am surprised by the timing but not by the choice.

…

This was definitely a “real world” pick and a nod in the direction of economists who are engaged in policy analysis and writing for the broader public. Krugman is a solo winner and solo winners are becoming increasingly rare. That is the real statement here, namely that Krugman deserves his own prize, all to himself. This could easily have been a joint prize, given to other trade figures as well, but in handing it out solo I believe the committee is a) stressing Krugman’s work in economic geography, and b) stressing the importance of relevance for economics