I have some questions about on the Baltic Dry Index (a rough guide to the price of moving dry goods by sea – more detail available here):

Research Economist at the Bank of England

I have some questions about on the Baltic Dry Index (a rough guide to the price of moving dry goods by sea – more detail available here):

Something very interesting happened to the share price of Volkswagen this week. The FT has the story:

Volkswagen’s shares more than doubled on Monday after Porsche moved to cement its control of Europe’s biggest carmaker and hedge funds, rushing to cover short positions, were forced to buy stock from a shrinking pool of shares in free float.

VW shares rose 147 per cent after Porsche unexpectedly disclosed that through the use of derivatives it had increased its stake in VW from 35 to 74.1 per cent.

…

[T]he sudden disclosure meant there was a free float of only 5.8 per cent – the state of Lower Saxony owns 20.1 per cent – sparking panic among hedge funds. Many had bet on VW’s share price falling and the rise on Monday led to estimated losses among them of €10bn-€15bn ($12.5bn-$18.8bn).

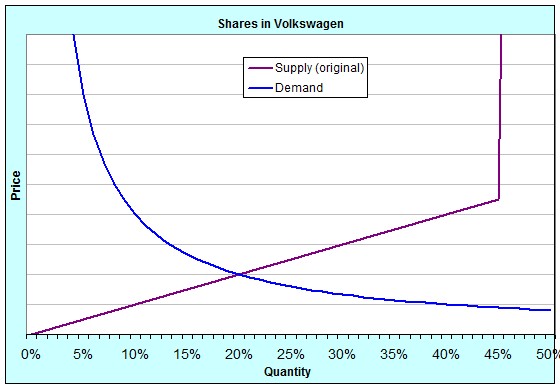

For my students in EC102, this is interesting because of the shifts in Supply and Demand and the elasticity of those curves. The buying and selling of shares in companies is a market just like any other. Here’s an idea of what the Supply and Demand curves for shares in Volkswagen were originally:

The quantity is measured as a percentage because you can only ever buy up to 100% of a company. Notice that the supply curve suddenly rockets upwards at around 45%. That’s because originally, 55% of the shares of Volkswagen weren’t available for sale. 20% was owned by the state of Lower Saxony and 35% by Porsche, and they weren’t willing to sell at any price [In reality, if you were to offer them enough money, they might have been willing to sell some of their shares, but the point is that it would have had to have been a lot]. We say that for quantities above 45%, the supply of shares was highly, even perfectly, inelastic.

Notice, too, that the demand curve is also extremely inelastic at quite low quantities. That is because a lot of hedge funds had shorted the VW stock. Shorting (sometimes called “short selling” or “going short”) is when the investor borrows shares they don’t own in order to sell them at today’s price. When it comes time to return them, they will buy them on the open market and give them back. If the price falls over that time, they make money, pocketing the difference between the price they sold at originally and the price they bought at eventually. A lot of hedge funds were in that in-between time. They had borrowed and sold the shares, and were then hoping that the price would fall. The demand at very low quantities was inelastic because they had to buy shares to pay back whoever they’d borrowed them from, no matter which way the price moved or how far.

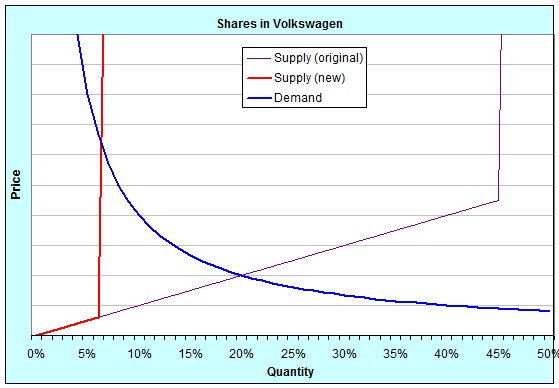

On Monday, Porsche surprised everybody by announcing that they had (through the use of derivatives like warrants and call options), increased their not-for-sale stake from 35% to a little over 74%. This meant that instead of 45% of the shares being available for sale on the open market, only 6% were. It was a shift in the supply curve, like this:

Because at such low quantities both supply and demand were very inelastic, the price jumped enormously. Last week, the price finished on Friday at roughly €211 per share. By the close of trading on Monday, it had reached €520 per share. At the close of trading on Tuesday, it was €945 per share. In fact, during the day on Tuesday it at one point reached €1005 per share, temporarily making it the largest company in the world by market capitalisation!

Who said that first-year economics classes aren’t fun?

Somebody much smarter than I am was kind enough to read my little post on Endogenous Growth Theory. At lunch today, they drew attention to this item that I mentioned:

I’m not aware of anything that tries to model the emergence of ground-breaking discoveries that change the way that the economy works (flight, computers) rather than simply new types of product (iPhone) or improved versions of existing products (iPhone 3G). In essence, it seems important to me that a model of growth include the concept of infrastructure.

The question was raised:

Could it be that times of significant social change have a tendency to coincide with with the introduction (i.e. either the invention or the adoption) of new forms of infrastructure? [*] A new type of mobile phone hardly changes the world, but the wide-spread adoption of mobile telephony in a country certainly might change the social dynamic in that country.

It’s something to ponder …

[*] My intelligent friend is not an economist and would probably prefer to think of this as a groundbreaking discovery rather than just the development of a new type of infrastructure.

From the fabulous Dr. Boli:

There’s a perennial question thrown around by Australian and British politics-watchers (and, no-doubt, by people in lots of other countries too, but I’ve only lived in Australia and Britain): Why do American elections focus so much on the individual and so little on the proposed policies of the individual? Why do the American people seem to choose a president on the basis of their leadership skills or their membership of some racial, sexual, social or economic group, while in other Western nations, although the parties are divided to varying degrees by class, the debate and the talking points picked up by the media are mostly matters of policy?

An easy response is to focus on the American executive/legislative divide, but that carries no water for me. Americans seem to also pick their federal representatives and senators in the same way as they do their president.

The best that I can come up with is to look at differences in political engagement brought about by differences in scale and political integration. The USA is much bigger (by population) and much less centralised than Australia or Britain. As a result, the average US citizen is more removed from Washington D.C. than the average Briton is from Whitehall or the average Australian from Canberra. The greater population hurts engagement by making the individual that much less significant on the national stage – a scaled-up equivalent of Dunbar’s number, if you will. The decentralisation (greater federalism) serves to focus attention more on the lower levels of government. The two effects, I believe, reinforce each other.

Americans are great lovers of democracy at levels that we in Australia and Britain might consider ludicrously minuscule and at that level there is real fire in the debates over specific policies. Individual counties vote on whether to raise local sales tax by 1% in order to increase funding to local public schools. Elections to school boards decide what gets taught in those schools.

That decentralisation is a deliberate feature of the US political system, explicitly enshrined in the tenth amendment to their constitution. But when so many matters of policy are decided at the county or state level, all that is left at the federal level are matters of foreign policy and national identity. It seems no surprise, then, that Americans see the ideal qualities of a president being strength and an ability to “unite the country.”

You can file this under “Things that Democrats in America wouldn’t dream of saying out loud.” Did Obama’s visit to his close-to-death grandmother seal his victory in the upcoming election? Think of what it says:

Yes, okay, it’s probably fair to say that Obama was coasting to victory long before his campaign announced his intention to go to Hawaii. But that’s not the point. The point is that it will have helped. Were it a close race, this may have decided it. As it stands, it guarantees that McCain can’t claw back any of Obama’s lead during those two days, making the Republican turn-around that much less likely.

A friend pointed me towards this piece on the Damn Interesting site. It was so interesting that I just had to share it with my little audience. Do read the whole thing, but here are a few titbits to whet your appetite:

…

Chelyabinsk-40 was absent from all official maps, and it would be over forty years before the Soviet government would even acknowledge its existence. Nevertheless, the small city became an insidious influence in the Soviet Union, ultimately creating a corona of nuclear contamination dwarfing the devastation of the Chernobyl disaster.

…

In 1951, after about three years of operations at Chelyabinsk-40, Soviet scientists conducted a survey of the Techa River to determine whether radioactive contamination was becoming a problem. In the village of Metlino, just over four miles downriver from the plutonium plant, investigators and Geiger counters clicked nervously along the river bank. Rather than the typical “background” gamma radiation of about 0.21 Röntgens per year, the edge of the Techa River was emanating 5 Röntgens per hour.

…

The facility itself was also beginning to encounter chronic complications, particularly in the new intermediate storage system. The row of waste vats sat in a concrete canal a few kilometers outside the main complex, submerged in a constant flow of water to carry away the heat generated by radioactive decay. Soon the technicians discovered that the hot isotopes in the waste water tended to cause a bit of evaporation inside the tanks, resulting in more buoyancy than had been anticipated. This upward pressure put stress on the inlet pipes, eventually compromising the seals and allowing raw radioactive waste to seep into the canal’s coolant water. To make matters worse, several of the tanks’ heat exchangers failed, crippling their cooling capacity.

…

[T]he water inside the defective tanks gradually boiled away. A radioactive sludge of nitrates and acetates was left behind, a chemical compound roughly equivalent to TNT. Unable to shed much heat, the concentrated radioactive slurry continued to increase in temperature within the defective 80,000 gallon containers. On 29 September 1957, one tank reached an estimated 660 degrees Fahrenheit. At 4:20pm local time, the explosive salt deposits in the bottom of the vat detonated. The blast ignited the contents of the other dried-out tanks, producing a combined explosive force equivalent to about 85 tons of TNT. The thick concrete lid which covered the cooling trench was hurled eighty feet away, and seventy tons of highly radioactive fission products were ejected into the open atmosphere.

Incredible.

The NY Times endorses Obama:

Hyperbole is the currency of presidential campaigns, but this year the nation’s future truly hangs in the balance.

The United States is battered and drifting after eight years of President Bush’s failed leadership. He is saddling his successor with two wars, a scarred global image and a government systematically stripped of its ability to protect and help its citizens – whether they are fleeing a hurricane’s floodwaters, searching for affordable health care or struggling to hold on to their homes, jobs, savings and pensions in the midst of a financial crisis that was foretold and preventable.

As tough as the times are, the selection of a new president is easy. After nearly two years of a grueling and ugly campaign, Senator Barack Obama of Illinois has proved that he is the right choice to be the 44th president of the United States.

Following on from yesterday, I thought I’d give a one-paragraph summary of how economics tends to think about long-term, or steady-state, growth. I say long-term because the Solow growth model does a remarkable job of explaining medium-term growth through the accumulation of factor inputs like capital. Just ask Alwyn Young.

In the long run, economic growth is about innovation. Think of ideas as intermediate goods. All intermediate goods get combined to produce the final good. Innovation can be the invention of a new intermediate good or the improvement in the quality of an existing one. Profits to the innovator come from a monopoly in producing their intermediate good. The monopoly might be permanent, for a fixed and known period or for a stochastic period of time. Intellectual property laws are assumed to be costless and perfect in their enforcement. The cost of innovation is a function of the number of existing intermediate goods (i.e. the number of existing ideas). Dynamic equilibrium comes when the expected present discounted value of holding the monopoly equals the cost of innovation: if the E[PDV] is higher than the cost of innovation, money flows into innovation and visa versa. Continual steady-state growth ensues.

It’s by no means a perfect story. Here are four of my currently favourite short-comings:

It’s old news by now, but in case anybody missed it, the excellent Bryan Palmer has resumed blogging at ozpolitics. This is a Good Thing ™.